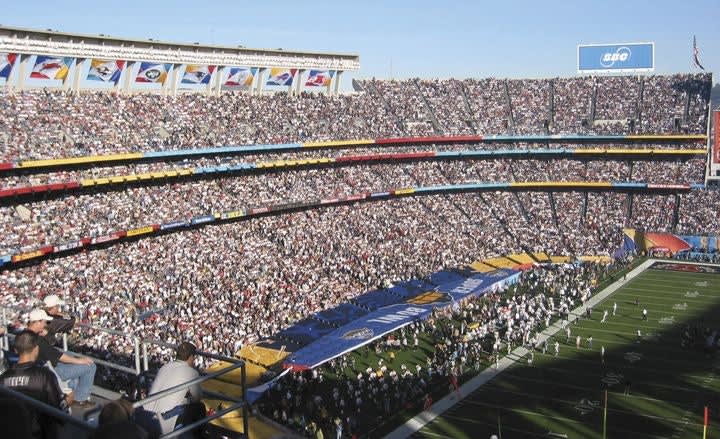

Post-9/11 America is a tense place to plan for huge gatherings of football fans in crowded urban areas

Major events like the Super Bowl pose an extraordinary challenge for law enforcement agencies, and there is no shame in admitting that sometimes we are simply overwhelmed with the scope and the complexity of these large events. When America's greatest sports spectacle comes to town, local agencies must wrestle with some serious concerns, including overall security, traffic control, parking, and crowd management. To cope with these headaches, planning must start months, if not years, in advance of "Game Day."

San Diego played host to this year's Super Bowl. And the police department of "America's Finest City" started "working the problem" more than a year in advance right after the 9/11 terrorist attacks in New York and Washington.

Post-9/11 America is a tense place to plan for huge gatherings of football fans in crowded urban areas. In that climate the Super Bowl is not just a world-class sports event, it's a rich target for a fanatic.

Consequently, in their planning of security for the big event, the San Diego PD had to deal with an elevated terrorism threat; a possible war with Iraq; the proximity of an international border; and an operational area that included a dense urban downtown district, a deep valley river estuary, an extensive commercial waterfront, and an international airport. To top it all off, California's massive budget woes have walloped local police budgets.

Unified Command

As planning for the security of Super Bowl XXXVII progressed, the threat of terrorists using Weapons of Mass Destruction (WMD) created an environment in which public safety and law enforcement agencies at the federal, state, and local levels were forced to evaluate incident management plans and identify new approaches. Agency planners recognized that no single organization or discipline was capable of dealing with the consequences of a WMD attack on its own. New strategies emerged that employed a unified command structure to approach a potentially catastrophic incident.

A unified command system provides direction and control to field forces. The teams are made up of law enforcement, fire, emergency medical services, explosive ordnance disposal, and hazmat personnel. These multi-disciplined response units are the anchor of the system.

In this system, field unit commanders, administrators, and emergency managers had to expand their understanding of local allied agencies' special capabilities, jargons, protocols, and procedures. Additionally, the methods individual agencies use for information exchange became a major concern. It was as if the decision makers had to learn three or four new languages. Fortunately, exercises and drills helped the responders find methods of coordination to further facilitate the integration of field unit capabilities.

As the big day approached, the unified response team concept became more accepted and familiar to all of the planners. But one critically important element was overlooked. It was a resource that all law enforcement officers are familiar with and use daily in our work, the community.

Other government and public safety agencies have not been practicing community-oriented or neighborhood-based strategies as we, in law enforcement, have for years. Consequently, because of their lack of familiarity with community resources, the planners did not integrate the extensive resources available within the private sector of our community. That changed quickly once the planners realized how much the public and private sector companies could bring to the table.

In the case of Super Bowl XXXVII, the resources of the community and businesses were considerable and essential to maintaining security. It's important to note here that the "community" in this case is not just San Diego. For a national event the size and scope of the Super Bowl, the community expands to encompass the entire nation.

San Diego security and safety planners were able to establish informal partnerships with a number of local, state, and federal private sector organizations. These included academia, industry, and non-law enforcement federal government agencies.

The Shadow Bowl

Federal support for San Diego was provided through a series of exercises called "Operation Gaslamp" and through the deployment of a suite of communications equipment called Infra Lynx.

The majority of private sector support was provided as part of "Operation Shadow Bowl," a large-scale demonstration of community readiness and medical response to a mass-casualty event. Operation Shadow Bowl offered a great opportunity to build field experience, to develop new biomedical technologies and, especially interesting to law enforcement, to test communication systems that enhanced the ability to collaborate and effectively respond to emerging disasters. It proved to be an extremely valuable exercise for decision makers, first responders, and hospital-based emergency medical teams.[PAGEBREAK]

Working Without Wires

One of the greatest benefits of the involvement of private sector companies and non-law enforcement government agencies in the security for the Super Bowl was the San Diego PD's full unfettered access to an array of wireless communications systems, sensors, surveillance cameras, and other monitoring and display systems.

The communications system was built in layers that could operate independently if necessary. For example, an additional backup operation center (OC) was established within the Operation Shadow Bowl Command Center, and a second backup operation center was set up at the Infra Lynx Command Center. In the event of a catastrophic failure of the primary OC, the backup centers were ready to go. If such a catastrophe occurred, the surviving staff would relocate at one or both of the backup sites. Additional staff was also tasked to respond to the OCs as needed.

In addition, the Department Operations Center (DOC) and the Downtown Event Command Post (DTCP) were linked via RoseTel Video Conferencing systems. Also, all of the video surveillance systems were linked between the OC sites to give the decision makers real-time video of what was happening in the field.

This communications web was critical when crowds exceeding 125,000 flooded into San Diego's downtown Gaslamp district. Using the system, incident commanders were able to send resources where they were needed in a timely manner.

Some Things Borrowed

A number of private and non-law enforcement concerns provided communication and surveillance tools to help maintain the security for the Super Bowl.

Santa Clara, Calif.-based Omnimedia Technologies supplied a stand-alone, streetlamp-mounted video camera that covered the main downtown venue. The system uses wireless cellular phone technology to transmit streaming video images. Images were sent to Omnimedia's secure video server and then uploaded to a secure Website that was used to monitor crowd size and behavior.

The University of California at San Diego brought in another video surveillance system for use in the downtown command post. These cameras were mounted on a light pole in the Gaslamp area and on the roof of the command post itself. The Gaslamp camera ran to the command post through a direct wireless link that was set up by Sky River Wireless Broadband Communications of San Diego.

Images from the cameras were transmitted to UCSD's equipment and software that measured crowd size in certain geographical areas. The computer would advise the incident commander when the crowd exceeded the limit for the area and it kept a running account of crowd size on an hour-by-hour basis. The system on the roof of the command post was used to count the number of vehicles entering and exiting the secure parking area and alert officers to intruders as they approached the building.

Another San Diego company, VivaMicro Wireless Vision, stepped up with equipment that streamed pictures from a large beach area venue across a wireless Internet connection. Crowds estimated at above 15,000 were easily watched and managed by the incident commander using a laptop computer.

Pacific Microwave Research of Vista, Calif., provided what turned out to be an invaluable tool for the decision makers in the field, at the Department Operations Center and in the Incident Command Post. The company's Tactical Video Receiver (TVR) is a handheld unit that displays video imagery transmitted by aerial assets or frontline surveillance platforms. To make best use of the system, two San Diego PD helicopters were outfitted with video microwave downlinks. The onboard cameras, both normal color and forward-looking infrared, were linked into the microwave downlink transmitter.

Pacific Microwave equipped officers in the DOC and the Incident Command Post with handheld receivers and one roof-mounted receiver system. The handheld systems were fielded by the on-the-ground field incident commanders. And they worked great.

On Saturday prior to the game, crowds flocked to the beach area venue for a concert and a helicopter was called in to provide overhead observation. With the helicopter overhead, the field commanders were able to see their areas of responsibility from the air. As one of the helicopters circled the event, the observer switched to infrared. In the "white hot" mode, the ground commander saw a large, dark hole develop in the middle of the crowd of 15,000-plus young people dancing in front of the stage. This was the development of a mosh pit, which was expressly prohibited as part of the venue's license. Because of information supplied by the Pacific Microwave equipment, the commander was able to contact the onsite promoters and stop the activity. This was easily accomplished via the telephone without the need to risk officer safety by placing them in the crowd to observe the behavior or take what would be an unpopular action in a crowd of 15,000 kids.

The roof-based Pacific Microwave system was used in the downtown Gaslamp district and offered the incident commander with video of crowd size and movement that he could communicate to the ground troops. As the crowds moved around the downtown area, they were met with officers at key points. This allowed the commanders to use fewer officers in a mobile posture rather than fixed posts where they were not needed.

Communications Backbone

Infra Lynx, a Virginia-based company with offices in San Diego, provided satellite communications, tactical cellular sites, and wireless broadband Internet access at all the out-lying command posts. This equipment was the backbone for all the other systems throughout the event.

Previously, Infra Lynx's Tac Cell system was used in New York City in the aftermath of the World Trade Center attacks to search for victims by electronically locating cell phones within the rubble. Although none were found alive, the effort did help locate remains.

The mission of security plans like the ones employed at Super Bowl XXXVII is to ensure that such technology is never needed again to find the remains of victims of a terrorist attack. And as law enforcement professionals, we need to remember that the "private sector" of business is made up of people in our community and they all have a stake in maintaining public security and safety.

As such, many of these companies are willing to lend a hand when we really need them. Their efforts during Superbowl XXXVII made San Diego and the thousands of football fans who flocked to the city safer. They donated the use of literally millions of dollars worth of equipment.

Super Bowl XXXVII was a perfect example of the best aspects of community-oriented policing. The community supplied additional communications equipment, medical support, situation awareness, and mental horsepower not normally at the disposal of the public safety agencies, and that was a huge assist that may have even saved the day had an actual incident developed.