While we're a far cry from replacing man with machine, technological innovations have vastly improved the safety, speed, and accuracy with which today's patrol officers do their jobs.

It's often said that in writing there are no original ideas, only new spins on existing themes. Hollywood appears to be hellbent on driving this point home, with plans to remake a sizable portion of its film library, including "Robocop." Nearly a quarter of a century ago, the movie was released with the tagline, "The future of law enforcement." While we're a far cry from replacing man with machine, technological innovations have vastly improved the safety, speed, and accuracy with which today's patrol officers do their jobs.

Even if we're not covered from head to toe in steel alloys like the cinematic centurion Robocop, our ballistic vests are more comfortable, durable, and dependable. Patrol vehicles are safer, and stocked with computers and cameras. Information and communications are sent and retrieved by the officer in the field with ever greater speed.

"Technology has been a wonderful thing for law enforcement in a number of respects," says Dr. Ron Martinelli, CEO of Martinelli & Associates and noted forensic and police practices expert. "It has provided us with a faster way of doing things: reports, crime analyses, forensics; it enhances our investigative ability and our ability to respond more rapidly to calls for service."

At the same time, Martinelli warns that overuse of technology in the field can detract from officer safety practices. "When you are in the field, especially in a patrol car, situational awareness is critical for your survival, the survival of your partner, and the safety and survival of the citizens that you deal with."

Finding the balance between adopting new technologies and employing well-trained officers who are not overly reliant on them remains a challenge for today's police departments. According to a recent study by the RAND Corporation, "While the role of technology will grow, the true value of technology is as a complement to human capacity for police work and problem solving-not a substitute."

Whether you are one to embrace technology or shy away from it, your ability to navigate the technological landscape will be an important factor in your future success in law enforcement.

Smile, You're on Candid Camera

Chief among cops' technological concerns today is video. The day of the anonymous, faceless Robocop patrol officer is not here yet, and whether you like it or not, every aspect of your job—calls, detentions, accident and crime scene investigations-will increasingly be subject to some form of video documentation. As some of this will come in the form of grainy security footage to be left to all manner of interpretation, or citizen cell phones that have been activated well after what actually started an incident, it behooves you to record your own perspective of the situation.

There is no shortage of products designed to record your every contact. From lapel cameras to dashboard cams, it's "COPS" live and on tour. Law enforcement utilizes cameras that can be permanently mounted in cars or hand carried by officers. We have cameras that switch on automatically when the car door opens or the siren activates. Video is digitally recorded, sent wirelessly to the station for monitoring, and cataloged and stored for later use in court.

The mere presence of a camera can change the dynamics of a situation, and you will find that some people will play to a camera-even yours. Others tend to get caught up in the immediacy of the moment, oblivious to the possibility of being recorded; some probably don't give a damn if they are. This means that you'll get all manner of spontaneous statements from suspects and witnesses that can expedite and close out investigations.

Camera usage encourages greater professionalism on your part, and locks people into a version of events that they would have a difficult time backing away from later. In the long run, you will come to realize that documenting your actions and investigations works to your advantage and can prevent frivolous litigation.

With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility

For the police officer, power comes in myriad forms, including the powers of arrest and the powers by which to effect that arrest.

Having advanced from the truncheons and straight sticks of yesteryear, today's cops have a wide range of mechanical and electronic weaponry available to them. Among the tools you may carry on your Sam Browne include handguns, TASERs, batons, magazines, pepper spray, handcuffs, portable radio, knives, recording devices, cell phones, and flashlights.

But with more and more items accruing on your arsenaled waist, keeping track of them can also become a concern. A Bay Area Rapid Transit officer's disastrous confusion between his sidearm and his TASER is a prime example. The extent to which Johannes Mehserle's agitated state and distracting influences played a part in that incident may be long debated, but the bottom line is that he should have been keenly aware of the tools he carried.

And therein lies a valid concern for today's rookie cops. Members of this generation-particularly those from metropolitan areas-have largely been raised in environs that prohibited imaginary gunplay. As a result, many of today's younger cops are no more familiar with firearms than with any other tool of the profession. Oftentimes, their first exposure to these tools occurs in the academy.

To avoid potential disasters, it is imperative that you acquire proficiency and comfort with your weapons and tools. It is far better to anticipate and address knowledge gaps in controlled environments than hope for some sudden epiphany when the bad stuff hits the fan. Maintaining an awareness of just where your tools are, training in how to transition between them, and developing the fine motor skills with which to retrieve them are all key.[PAGEBREAK]

Vehicular Performance

Most patrol officers develop a love-hate relationship with their patrol cars. Today's factory models are definitely faster and safer when they reach your fleet than your father's Oldsmobile. But by the time the gun rack, radio equipment, cameras, computers, MDTs, and other equipment are added, you can end up feeling like a sardine wedged into a tin can for much of your shift.

The aforementioned surveillance cameras, mounted fore and aft of the patrol car, not only make capturing and storing video easier for you, they can also broadcast images wirelessly. Supervisory personnel at the station, using real-time video information, can provide direction during pursuits or other technical callouts. Many patrol cars are equipped with automated vehicle license plate readers that can scan thousands of license plates per minute and inform you if the car is reported stolen or is linked to a suspect.

Some departments have taken to installing GPS tracking devices in every patrol car. This means your watch commander will know where your patrol car is and how long it has been there: Goofing off just got a whole lot harder. The good news is that you, too, will know where your fellow officers are. This can not only facilitate coordination of radio calls, but hopefully mitigate the potential for radio car vs. radio car collisions.

When combined with centralized mapping technology, departments can pinpoint the locations of criminal activity and officer responses to develop strategies for improving patrol coverage. State-of-the-art maps displayed in patrol cars can also inform officers when they pass by locations where suspects reside or recent crimes have occurred.

Having access to all of this electronic wizardry inside a patrol car is fast becoming a necessity in today's technological world. It allows officers to concentrate more on policing than mundane clerical work, but can also come with a cost. Besides reminding you to lose a few extra pounds, these components may become airborne projectiles in a collision.

State-of-the-Art Databases

From Riverside, Calif., to Sellersberg, Ind.; from Boston, Mass., to Farmington, New Mexico, law enforcement agencies prominently promote themselves as technological innovators. Some, such as the Kenner (La.) Police Department, use such innovation as recruitment inducements.

Others like the Tigard (Ore.) Police Department recognize the need for technical competency and openly recruit police technology specialists. But while filling computer-centric positions makes sense for the routine supervision and maintenance of fingerprinting databases, computerized crime mapping, and records management systems, there will be continual and growing emphasis on officers being computer literate enough to handle much of the day-to-day load.

This reality extends over the law enforcement landscape and is manifest in virtually all aspects of the profession. Special weapons and tactics teams are increasingly computer-dependent, as modern technology allows them to use all manner of remote surveillance tools to acquire intel and retrieve schematics for residential and commercial layouts.

When it comes to entering data, the adage "garbage in, garbage out" is most applicable. One officer transposed two digits in running a firearms check. The weapon came back clear when it actually had a hit entered on it. The suspect and the firearm were released and less than a week later the weapon was used in the shooting deaths of multiple victims. Overcome with remorse, the officer became yet another victim when he committed suicide.

With such import being placed on the proper use of technology in the field, it stands to reason that the more computer savvy you are, the greater the edge you will have on your competition.

Because You Can, Doesn't Mean You Should

Determining the optimal amount of technology that should be required of officers is a hot topic among law enforcement administrators, risk managers, and policy analysts.

As retired LAPD lieutenant and author of "Police Technology" Raymond E. Foster notes, "There are many aspects of technology that have improved police work. Perhaps more importantly, there are some aspects of technology that tempt us to violate basic officer safety field tactics."

Martinelli agrees that tactics trump technology. "We need to be very careful about what technological wizardry we force upon our officers," he says. "Officers have to process what they are experiencing. They have to analyze what they are seeing. They have to develop tactical plans and engage those tactical plans. When milliseconds count, it is more important that officers have a good sense of situational awareness and are not distracted in their basic law enforcement functions."

Tomorrow's Technology Today

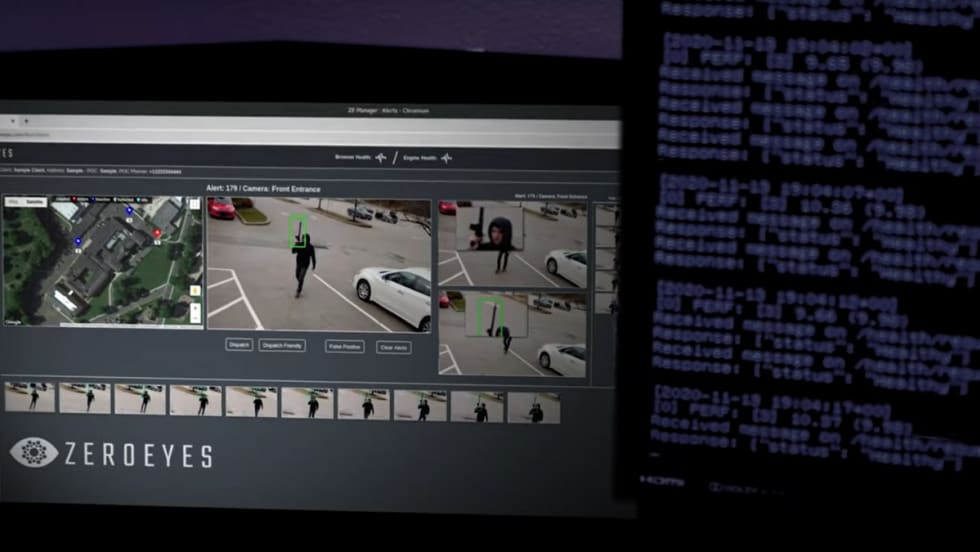

It is the nature of technology that new innovations are constantly being researched and implemented. Among the products on the horizon for law enforcement are portable printers to expedite field citations and arrests; facial recognition systems, DNA and print scans to rapidly verify peoples' identities and aid in the identification of wanted felons; weapons recognition systems that can identify an armed person from a safe distance; and safer deployment of less lethal weapon systems.

Despite our increasing dependency on technology, the future of law enforcement will not likely come in the form of Robocop or The Terminator.

Martinelli places equal emphasis on an officer's non-technological skills. "Even in these technologically advanced ages, law enforcement is ultimately and will always be about people and relationships: the ability to talk to people, the ability to engage people, the ability to focus on officer and citizen safety, the ability to conduct pre-contact threat assessments, and to have an officer function at a level that is least distracting."

Each generation of law enforcement recognizes the unique advantages and challenges the next will face as the torch is passed, and with this comes an understanding that rookie officers will hit the streets with certain perks that their predecessors lacked.

As long as you view them as supplemental to tactics, by keeping up to date with technological changes you'll stay dialed in.

Make that wired in.