In the 30 years since Police Magazine debuted as Police Product News, law enforcement has changed drastically, as has the world we live in. It's hard to imagine how we lived without the Internet and cell phones just a few years ago, let alone without the semi-automatic sidearms and OC spray officers have come to depend on as tools of the trade. Add to that the advent of DNA testing and large-scale terrorism attacks on American soil and it's difficult to believe we live in the same universe as officers in 1976.

On the occasion of our thirtieth anniversary, Police Magazine decided to contact veteran officers and ask them how law enforcement has changed in the past three decades.

Michael Browne is currently deputy chief at the Torrance (Calif.) Police Department. He grew up in Torrance and joined the department in 1973 as an officer. Browne has worked patrol, detectives, homicide, and Internal Affairs.

Dennis Jurasz retired from law enforcement in 1994 after serving 20 years with the same agency and is currently manager of training for Delta Airlines Global Services Security Division. He joined the North Tonawanda (N.Y.) Police Department as a patrolman in 1974.

Wayne Laing is back working as a deputy with the Natrona County (Wyo.) Sheriff's Office, where he got his start in 1975. He left the agency to join the Evansville (Wyo.) Police Department in 1983, where he served as chief for several years.

Tim Shermer of the Raleigh (N.C.) Police Department has been with the agency since joining the academy as a recruit in 1979. He's now a major and division commander for the special operations division.

Jon Sperling is currently a patrol sergeant with the Brevard (Fla.) County Sheriff's Office. He began in law enforcement in 1977 as a Police Explorer in West Hartford, Conn. He served as a K-9 handler in the Air Force before joining Brevard County in 1987.

Bob Vann is a constable with the Travis County (Texas) Constable's Office in Precinct 2, which is in the state capital of Austin. He began in law enforcement as an officer for the City of Killeen (Texas) Police Department in 1973.

POLICE: What do you miss most about the days when you started out in law enforcement about 30 years ago?

Shermer: It was a simpler time back then. Sometimes I miss the simplicity of picking up a radio and saying, "Ten-Four" and you just go to the call. [Laughs.]

Browne: I miss being out in the field with the officers and putting the bad guys in jail. I mean, that's what you hire on to do as a young officer, to make the city safe. And as you promote and move up, your hands-on involvement really gets limited. It was fun.

Jurasz: I miss the closeness of the brotherhood.

Browne: I agree. When I first came on Torrance PD in 1973, most of the officers lived in the city. It was more of a family. Now you don't have that close a connection.

Vann: I miss that the media was different then. The reporting was fair and usually supportive.

Now they pick apart anything law enforcement does to make a story bigger and that really hurts with community support. The media was part of the community support back then.

I feel that the silent majority still supports law enforcement, but to read media coverage, it makes it appear that they don't.

Jurasz: You're right. The public believed you were out there doing the job you're supposed to. And if someone got bailed out in the morning and he had bruises on him, they'd say, "Hell, you got picked by the cops. They must've had a reason. You must've had it coming."

Sperling: I think public opinion has changed in some part because of the media. It depends on the time. After 9/11, every cop was a hero. After Rodney King, every cop was a racist.

And because of all the dramas and reality shows, they (the public) think all we do is have car pursuits and arrest criminals. That's just a small portion of the job.

POLICE: What are you glad has changed since then?

Sperling: The technology has made the job easier. The laptops, computers...I don't know how I did my job without them.

Vann: The better training, variety of training, and the development of better tools for our trade. All of that has made the community and police officers safer and more professional.

Jurasz: In '74 there were a lot of things cops never should have done. It's just that simple. And I understand that was the old style. But I'm glad that's changed.

You could stop for lunch, walk into a barroom, have a sandwich and a beer, and it was perfectly acceptable.

And the cops themselves, at times they were the biggest thugs in the neighborhood. I can remember some of the guys that were rookies right after WWII, they were still on the job when I got on and they would take street justice.

The way society has evolved I don't think that has any place in law enforcement anymore.

POLICE: With all that has changed, would you approach the job differently if you were a rookie today?

Vann: As much as I have enjoyed my career, I don't think I'd be as willing to start in this profession today. There's been that big of a change.

Shermer: I would approach it differently now. In 1979, I joined a police department with a four-year degree in criminal justice. But I didn't have military experience. To get ahead, you've got to have the training and you've got to have an education. Military and college together would be a great combination.

Jurasz: Yeah, I would focus much more on my professional education.

Get a degree as early in your career as you can and plan for the end of the policing career. There is life after police work, but it's got to be based on a plan of attack early on. I was late getting into the plan of attack.

POLICE: How has technology for law enforcement changed in the last 30 years?

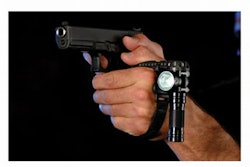

Vann: From my viewpoint, the biggest change in policing, period, has been the switch from revolvers to auto loaders.

Stepping up to the proper auto loader with the clips and the ease of loading and having the firepower available, it was just a world of difference when the agency I worked for actually started letting us use them. A lot of agencies fought that for the longest time.

Shermer: Technology makes life easier. Now we have what we call Cops Mobile Reporting, where you do all your police reports from your car or on your portable computer. The paperwork's a lot easier than it was...as long as you can run that kind of technology. The kids obviously know how to use that technology more than us older guys.

Sperling: It's made the job easier because you can spend most of your time in the field, not going back to the office. We have cell phones and we can instant message each other instead of having to meet or instead of having to stop at a payphone.

Jurasz: It used to be, you'd go back to the police station and make three copies of your report with carbon paper on a manual typewriter. Now, ask a 21-year-old at the academy, "What's carbon paper?" "Have you ever seen a typewriter?" He'll say, "I saw them in a museum once." [Laughs.]

POLICE: Have some officers become too dependent on technology?

Sperling: Yeah, there can be a time when if the computer goes down and there's no GPS capability, the younger people can't find a street with a map.

Laing: The MDT is just like your home PC, and sometimes they'll crash on you. But you still have a radio to rely on. And just about everybody has a cell phone on them these days. So unless you have a complete power outage or something, you can get information that way.

Vann: In my early law enforcement career, we had radios that were on a band where sometimes skip would be introduced. We'd be talking to a dispatcher that was several hundred miles away and not be able to get a hold of ours. It's something that modern-day police officers have probably never experienced.

Jurasz: In 1974 when I got on the job, there was no such thing as a portable radio. I can remember the oldtimers saying, "Hey, kid, listen. If we go into a bar fight, only go in as far as you can fight your way out so you can go back to the car and call for help.

Vann: As far as advancements in technology for safety, the Taser stun gun is probably one of the best tools to come along. It gives you a choice to use a tool that may otherwise have been a bullet. Now we have a variety of tools.

Shermer: And of course, there are so many more vest companies than there used to be.

Vann: I can't remember anyone when I started even knowing what a bullet resistant vest was.

POLICE: How has police culture changed?

Sperling: The make-up has changed with the diversity of law enforcement officers. When I first started in the '70s, there were no female patrol officers, there were very few minorities. There also used to be a height requirement, which has been completely eliminated. Now you get a better representation of the community.

Shermer: I've seen a big change with our minority population at the Raleigh Police Department: increasing, going up in rank, and it's been great. It helps out a lot in problem-solving in predominantly minority areas. It really has changed the culture from that point.

Vann: In Texas in those days we had female officers. But I guess very few of them actually wanted to get into law enforcement.

Jurasz: I disagree. In 1981, I married a cop. So I know firsthand what she went through, and yeah, it was tough. The first female officers, they had it really hard. I think it's still the same way for a lot of female officers. They say you've got to be twice the woman to be half the man. It's true in a lot of ways. And you still see it.

Sperling: Personally, I like working with female officers. They have a different outlook on things, a different way they handle people.

Jurasz: Exactly. My wife taught me a ton about law enforcement, especially how to work with people. She worked swing shift like I did. She would go to work and wear the whore-red lipstick, red nail polish, and a ton of the cheapest, nastiest perfume that you can imagine.

I was like, "What the hell are you doing?" And she said, "When we go to bar fights or we go to a bar for an unwanted guest, believe me, it's much easier to talk them out of the bar than it is to fight them out of the bar." And she could walk up and say, "Hi, honey, how are you? What are you doing in here? Why don't you and I go outside to talk?" And they would saunter outside with her.

Now I can tell you, there's a lot that I learned from that. It's much easier to talk to people. And I wasn't one of those talkers.

Laing: I think the treatment female officers are getting now is much, much better.

POLICE: What about the sentiment that policing is just a job to new officers? Is that a new aspect of police culture?

Sperling: Yes. In the past, most officers really wanted to be police officers. Now some are taking it because they see it as a halfway decent job without a lot of training. They all want to be CSI agents and detectives in a year.

Part of it is the media not giving an accurate idea of what the law enforcement officers do. It's also that there's some issues with the X and Y generations. They ask questions more, which sometimes can be good. But in police work sometimes we don't have time to ask questions. They don't have the military bearing.

Shermer: It's a whole different culture and generation we're dealing with. A lot of them have the attitude, "I want mine and I want it right now." They don't want to work for it.

Jurasz: The job was everything then. It was a career. It was a way of life. That's what you did, that's who you were. I mean, 24/7 you were a cop, you know? I'm retired, but in my heart I'm still a cop.

I don't see the new warriors in there. I don't see people with that burning desire in their heart.

Shermer: We're a very young department. I would say our average age at field operations, our largest division, is 25 to 28 years old. We've had to adapt somewhat to the new generations. Because they'll be the ones running this department in five, 10, 15 years.

Vann: And I think the new generation has gotten some things right. Back then, about the only friends we had were each other or our relatives. Now peace officers are more likely to have many more non-police friends than you could even imagine back then.

I think today's police officer is more involved in his community, his church, other organizations outside of law enforcement. And it's a very healthy thing.

And the code of silence that everybody used to talk about, it probably existed at almost all the agencies back in the old days. It's harder to find that now.

Laing: I think it has evolved. You used to have the "good ole boy brotherhood." I think the people in law enforcement are more professional now.

Shermer: Definitely. I mean, just the way our officers look, the cars they drive, the equipment they have and can operate, the way they present themselves, it's totally different. They're not the donut-eating cops that we get kidded about from years and years ago. Just a whole different generation.

Sperling: I think the job has gotten more professional with departments getting accredited, certifications, and advanced training classes. Police officers are also held to a higher standard now than in the past.

POLICE: Speaking of standards, how have the qualifications for becoming a police officer changed, and what has that meant for police work?

Laing: I think some of the changes they've made are excellent and help determine good candidates for the job.

The background investigations they're doing now are much better than they used to be. They're more in depth. And they're doing psychological examinations, which really helps.

Shermer: When I came on to Raleigh PD in 1979, you had to run a mile-and-a-half in so many minutes and do so many push-ups and sit-ups and you were good to go.

Now we've got a physical training assessment that's more job oriented.

You crawl through a tunnel with your gear on, you've got to knock a door in, you've got to crawl over a wall as if you were in a footchase. That type of stuff.

We often wondered what was the use of going out there to run a mile-and-a-half when if you haven't caught him in the first hundred yards, you're probably not going to catch him anyway on a foot pursuit. [Laughs.]

Laing: Sometimes agencies' qualifications get a little stiff in some places and they probably miss out on hiring people that would do an excellent job.

Browne: Well, we hire employees that don't have a degree. But honestly, part of our skill set is you have to be able to take your thoughts and put them on paper. And if you can't do that, really you can't fit into police work.

Shermer: And it's a life experience. College is a great benefit.

Sperling: Our department still doesn't have any requirements for college. We do have a lot of people with bachelor's and associate's degrees, and road deputies with master's.

But the police academy training has gotten longer. And there are more training opportunities at the academy level and for advanced training when you come out.

Vann: I think the qualifications have just gotten better. I can remember that when I applied, all I did was go in for what was apparently an oral review board-I didn't know what it was-and that day they put me on the street.

They gave me a set of car keys to a marked patrol unit, a map of the city, and told me where my area was. They put me in a marked patrol car. I didn't have a uniform yet so I went out in a suit and tie.

In those days the state of Texas didn't require you to go to a police academy before you were put on the street. You were allowed one year to actually go to the academy.

Laing: You still have a year to enter the academy in Wyoming. But you have to go through an intense 16-week program with an FTO first. And you aren't given a gun until you qualify with it.

Vann: There is a lot more to the application process now, which has helped to make this profession worthy of the respect it deserves.

POLICE: How do you see the future of law enforcement?

Vann: The future may be a little bit of a downer. I don't think most people understand that the future of law enforcement in the United States is really going to be dealing with the war on terror on a daily basis and on our homefront. It's not going away.

Jurasz: And everybody's so worried about a person's rights, about being politically correct, "Don't do profiling." I mean heaven forbid you should insult someone.

If I was a terrorist and I wanted to blow up a plane right now I would take the guy that looks the most like a terrorist and send him through airport screening. Because everybody's so scared to death that they're going to get sued, get chastised for "profiling" this individual, that this guy with the long beard and saying, "I'm going to meet my maker and get my virgins," nobody would say a word to him. They'd just walk him through security.

Laing: I think our job is only going to get harder because of the global terrorism that's going on. But I believe that the training we are getting now and giving to our people is going to help us a whole lot in defeating that.

Shermer: We've got to think way outside of the box. I know it's a big catch phrase.

We've still got to do the basics of protecting and serving. But there's so much going on out there in the world that affects even local agencies, you've got to think about the partnerships you've got to form, not only with other police departments, but also with fire and EMS and emergency management, also private security consultants.

The old days of doing your own thing are gone. And the days of the police being responsible for everything? That's over with. People have got to step up to the plate and be part of it. Citizens sometimes have to police themselves. They can't expect the police to do everything.

Vann: With all that's going on, I think this nation needs to start paying a salary to police officers like their life depended on it. But that's just a hope. I don't know that I see that happening.