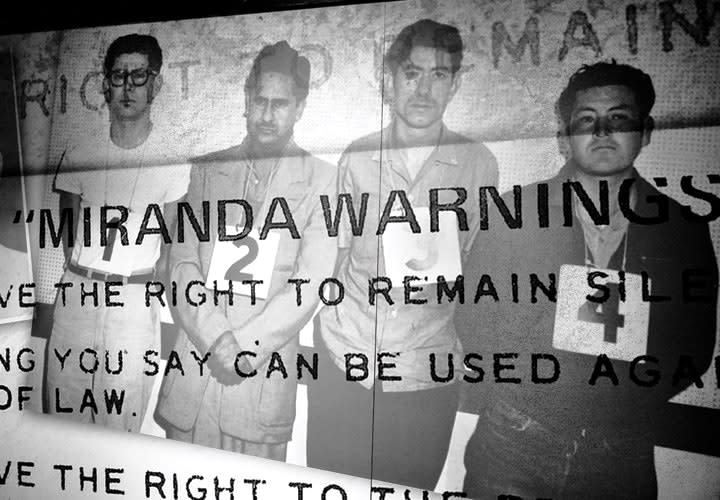

Officers on the job before 1966 knew that the right to remain silent was guaranteed by the Constitution, but no officer from that era ever thought it was his job to remind offenders of their rights. That changed with the arrest of Ernesto Miranda in March 1963 and the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision that followed.

No American law enforcement officer ever used the words, "You have the right to remain silent," before 1966.

Officers on the job before '66 knew that the right to remain silent was guaranteed by the Constitution, but no officer from that era ever thought it was his job to remind offenders of their rights. That changed with the arrest of Ernesto Miranda in March 1963 and the subsequent appeals of his conviction that resulted in the landmark U.S. Supreme Court decision Miranda v. Arizona.

Carroll Cooley was a fairly new detective working for the Phoenix Police Department back in 1963. He was assigned to investigate the violent assault and kidnapping of a young woman on her way home from work. Ernesto Miranda was a convicted criminal who was out of prison and on the streets of Phoenix. Tracking down leads on a car brought Cooley to the parolee's doorstep.

Miranda was linked to the crime and brought to the police department for an interview. During the interview, he admitted to the assault and kidnapping. Miranda was convicted of kidnapping, rape, and armed robbery. He was sentenced to prison. Case closed. At least that's what Cooley thought.

The Supreme Court

During the early and mid-1960s era of policing, arrests were made, confessions were obtained, and cases were prosecuted without giving a second thought to telling arrestees about their Fifth Amendment and Sixth Amendment rights. Officers were supposed to respect the rights of the accused; that fact was never in question. What did come into question was whether officers had a responsibility to tell suspects of their rights.

Miranda was literate, educated to the 8th grade, and volunteered his confessions knowing the consequences. Defense and appellate lawyers would argue to the contrary.

Miranda's arrest and conviction set forth a judicial process that lasted for more than three years. In 1966, Miranda v. Arizona was one of four cases that were brought before the U.S. Supreme Court dealing with custodial interrogations. All of the cases brought into question the rights of the accused and the responsibility of officers to advise the accused of their rights.

On June 13, 1966, the Court ruled that Miranda's confession could not be used against him because he was not advised of his right to remain silent, right to counsel, and what would happen if he talked. At Miranda's second trial, his confession was not used. But he was convicted a second time and sentenced to 20 to 30 years in prison.

Miranda was paroled in 1972, and he began selling autographed Miranda warning cards for $1.50. Arrested numerous times for driving violations, he eventually lost his license. He was also sent back to state prison for a parole violation, after he was arrested for possessing a gun. On Jan. 31, 1976, following his release from prison, Miranda was fatally stabbed during a bar fight in Phoenix.

Refining the Law

Of course the death of the man named Ernesto Miranda did not end his case's impact on law enforcement procedures. "Miranda Warnings" are ever changing in their application and interpretation just like every other aspect of a police officer's job.

Police implementation of Miranda warnings has changed over the years. When officers first got their marching orders to "read them their rights," they read the rights to everyone they questioned. Stop a man on the street to ask what he's doing, read him his rights. Everybody gets their rights read. That's the way it was in the mid '60s. Officers felt they were talking suspects out of a confession rather than trying to get one.

Thankfully, that's changed. Year after year, the application of Miranda rights has grown more refined. Miranda has now been defined to apply when two conditions are met. It must be a custodial interview and questions must be asked about the crime. Of course, "custody" is subject to judicial interpretation.

Miranda Today

In a recent case in Maricopa County, Ariz., a judge ruled in favor of a defendant whose attorney claimed that his Miranda rights were not read to him prior to a confession.

Detectives were investigating a teenager's claims that an adult touched her inappropriately. Like many other cases of this nature, a great deal of the case relied on the interviews of the victim and the accused. The detectives wanted to hear both sides of the story to see if a crime was committed. They did a non-custodial interview at the adult male's home. The interview did not result in an arrest, but it did result in the suspect's partial admission to the crime. After an interview with the victim, the detectives developed probable cause and arrested the suspect. Post-arrest, they read him his rights. He exercised his right to remain silent, requesting an attorney.

In a pre-trial hearing, the defense asserted that the detectives should have read the suspect his rights before the first interview; therefore the confession was not admissible. The prosecution argued the custody pretext was not met. The judge ruled for the defense. Without the confession, the case was never prosecuted.

This case is an excellent example of what officers face every day when weighing Miranda issues. If you get back to the basics of what the 1966 Miranda decision was all about, you'll remember that the defense claimed Ernesto Miranda was not educated enough to understand his rights, so the officers should have made sure he understood his rights before questioning. The recent Maricopa County case involves an accused with many years of college and there was no question as to his understanding of his rights.

Cases like the Maricopa County case have helped to refine the application of Miranda for officers. Miranda issues frustrate officers, but they adapt their processes to take into account new judicial interpretations that strengthen or weaken Miranda issues. Most officers take solace in the fact that they are only one part of the greater judicial process and, like the officers policing in the 1960s, they follow the rules and do their part to put criminals in prison.

The exact Miranda warnings were never defined by the Warren Court, but the concepts were clear. You have to tell accused persons of their right to remain silent before they are questioned in a custodial interview. You have to tell them what will happen if they choose to talk. The accused must be told that they can have an attorney with them during questioning to help protect their Fifth Amendment rights. They must be told that if they are indigent, they can have an attorney appointed for them free of charge.

Mark Clark is a 27-year veteran police sergeant. He has served as public information officer, training officer, and as supervisor for various detective and patrol squads.