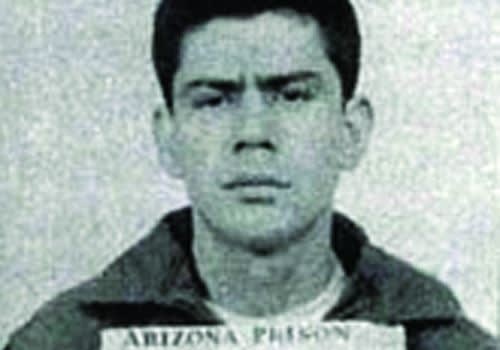

The genesis of the Miranda warnings can be traced to March 13, 1963, when Ernesto Arturo Miranda was arrested by officers of the Phoenix Police Department for stealing $4 from a bank worker and for the kidnap and rape of another woman. He already had a record for armed robbery, as well as a juvenile record that included attempted rape, assault, and burglary.

The police took him into custody and transported him to a police station. At headquarters, the victim of the sexual assault was unable to identify Ernesto Miranda as her attacker. The police brought Miranda to an interrogation room, where they questioned him about the crimes.

At the time, Miranda was 23 years old, indigent, and had not completed ninth grade. At the beginning of the interrogation, Miranda expressed his innocence. After about two hours of interrogation the police emerged with Miranda's signed confession to the crimes. The interrogation techniques used by the police were quite mild, and there were no objectionable methods used that might have rendered the confession "coerced" in the Due Process sense.

At the trial, Miranda's defense team moved to suppress the confession on the grounds the suspect had not been made aware of his Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination. The confession was admitted into evidence and Miranda was convicted of rape and kidnapping and sentenced to 20 to 30 years imprisonment on each charge, with sentences to run concurrently.

The case was appealed to the Arizona Supreme Court, which affirmed the trial court's decision. The Arizona Supreme Court's decision was heavily predicated on the fact Miranda did not request a lawyer.

In 1966, the U.S. Supreme Court reviewed the confession and the officer's testimony. Miranda's confession was written on pages that contained the words, "this confession was made with full knowledge of my legal rights, understanding any statement I make may be used against me." Despite this, it was clear that Miranda had never been verbally advised of his right to counsel or his right to have a lawyer present during his questioning. The police never told Miranda of his right to not be compelled to incriminate himself.

The Supreme Court decided in a 5-4 ruling that without these warnings all statements Miranda made were presumed to have been compelled by the inherently coercive atmosphere of custodial interrogation, and the statements were therefore inadmissible under the Fifth Amendment. The Supreme Court went on to say that the very nature of a custodial police interrogation is intimidating and a suspect must be advised of his rights to counterbalance this intimidation.

The Supreme Court reversed the lower court's decision and remanded the case for re-trial. Ernesto Miranda was retried for the crimes. The confession was not admitted into evidence. And it didn't matter; he was convicted and sentenced to 20 to 30 years in prison. In 1975, he was paroled.

Upon release, Miranda hung around bars in rough parts of Phoenix. On Jan. 31, 1976, a bar fight broke out; Miranda was fatally stabbed. When the police apprehended a suspect, they advised him of his rights per Miranda. The suspect exercised his rights and made no statement. No charges were ever filed in the stabbing death of Ernesto Miranda.

Related:

Miranda Warning Issues