They cruicial part of hurricane response and preparation is early planning and building relationships.Photo Illustration: POLICE, National Weather Service, SC Emergency Management Division

They cruicial part of hurricane response and preparation is early planning and building relationships.Photo Illustration: POLICE, National Weather Service, SC Emergency Management Division

When tropical storms and hurricanes threaten coastal areas, both state and local agencies must be prepared. A large part of the success or failure of an area’s dealing with a catastrophic storm hinges on planning well in advance and the development and refinement of those plans often span many years.

“It’s all about planning and relationships,” says Col. Neil Baxley, commander of the emergency management division of the Beaufort County Sheriff’s Office (SC) since October 2013.

His backstory relating to hurricanes starts back in 1979 when he was a young Marine at Paris Island, the main recruit depot for the eastern US, during Hurricane David. Later he supervised the evacuation of Hilton Head Island ahead of Hurricane Hugo in 1989. Moving forward, he led emergency management efforts during Matthew, 2016, and Irma, 2017, and has been instrumental in planning with other local and state agencies.

But how things operate now in Beaufort County was largely influenced by a 1999 hurricane.

Hurricane Floyd Lessons

In 1999 the area was impacted by Hurricane Floyd, resulting in the call for a full evacuation that was heeded by about 75% of the population. While much of the public left town, first responders remained.

“We housed the deputies in the detention center because we moved the prisoners out, moved them to Columbia. We housed them in a big multipurpose room and fed them jail food, which was not necessarily what they were looking for,” Baxley explains. “When it was over, there was so much complaining from the troops that I went to the emergency management director and said, ‘We have to do this better than what we just did.’”

Less than a year later, Baxley recalls, the upper South Carolina coast was threatened by a hurricane in Georgetown and Horry counties. State resources were deployed; however, lawmen were left manning traffic control points for more than 24 hours without any relief or supplies.

“The Red Cross rode around and gave them a lollipop and two bottles of water, and that was all they got,” says Baxley.

“I sat down in the state meeting and I said, ‘We have to do better than this.’ We cannot expect our people to be the solution to the problem when we don't treat them any better than this. I couldn’t do much to influence the state level plans, but I could do a lot to influence the Beaufort County plan, so I started working with the emergency management director at that time. And first off, we said ‘Let's solve the feeding problem.’”

Learn More: Disaster Preparation & Response Guide

Providing for Deputies

The sheriff’s office first made arrangements with local restaurants to help feed deputies during a storm, but none of those businesses at the time had generators. Baxley says the department also partnered with the local hospital, which had a generator and cafeteria. With all such elements of the feeding plan, there were written agreements and fee schedules.

“We said ‘If you will continue to feed us up until the storm gets so bad you cannot stay open, we will house your staff with our staff. We've got the power company and we'll get power restored back to you quickly so you can continue to feed us,’ same agreement with the hospital,” he details.

At the hospital, patients were evacuated but the department did not want to place deputies into patient rooms. However, the officers were simply housed in other hospital areas. The hospital agreement expired, so the sheriff’s office shifted to considering the local high school, and that is where deputies and other personnel were housed during Hurricane Matthew.

But the generator only powered emergency lighting and the IT system. Plus, every time someone exited a door, the alarm system activated. There was no air conditioning, no hot water, and no regular lighting. That meant it was time to find a better option.

The sheriff’s department worked out an agreement with a local church for housing deputies in the north end of the county. There is a full-service kitchen and the sheriff’s office installed a transfer switch so that a large departmental generator can be deployed and connected to fully power the facility. The sheriff’s office also can deploy the generator to the church in the event of winter weather, so it can serve as a warming shelter for area residents.

In the southern part of the county, deputies are now housed at the University of South Carolina Beaufort Campus and fed in the cafeteria – all arranged through written agreements including fee and reimbursement schedules. The department currently has more than 50 memorandums of understanding or contracts with organizations that will provide some type of support for the agency during a hurricane or related disaster.

“We solved the feeding problem; we solved the shelter problem. That takes care of our troops and that allows us to be the solution for everybody else's problems,” says Baxley.

This National Weather Service map shows the track and timeline of Hurricane Matthew.PHOTO: National Weather Service

This National Weather Service map shows the track and timeline of Hurricane Matthew.PHOTO: National Weather Service

Out-of-Town Location

The sheriff’s office also has agreements in Hampton County and Barnwell County to assist if first responders need to evacuate from Beaufort County. Over 3,000 people will relocate to Barnwell County and the command element and the policy group of all the municipalities, the mayors and county administrators, will shift to Hampton.

“We built a building in Hampton, adjacent to the Hampton emergency operation center, that we own. It’s a miniature emergency operation center, a miniature dispatch center, and a miniature government center,” Baxley explains. “That puts them about 40 miles inland, so it takes storm surge out of it completely and reduces the wind impact.”

Baxley credits his predecessor and mentor, the previous emergency management director who served 31 years, with pushing to get approval for the facility to be built in Hampton.

“Frankly, we've seen some other agencies that have an alternate plan, but it's nowhere near as robust as ours,” Baxley adds.

The department even inked new deals this year for churches to provide housing in Hampton County. For those evacuated to Barnwell County, housing would be provided through the school district and agreements are in place for school cafeterias to feed first responders. The sheriff’s office even has local agreements with fuel vendors in those counties so deputies can refuel and respond back to Beaufort County following a storm.

Dispatch and EOC

The dispatch center operates within the primary building at the Beaufort County Sheriff’s Office and can continue operation through a Category 3 hurricane. In the event of a Category 4 or 5 hurricane, dispatch would be evacuated, and services would then be provided from the building in Hampton, explains Capt. Adam Zsamar.

Either Baxley, or Zsamar in his absence, will activate the emergency operations center (EOC) on a limited basis after a storm is named and the National Hurricane Center and National Weather Service indicate the storm is likely heading for South Carolina.

Learn More: How Cellular Networks Keep First Responders Connected When It Counts

“At a point in time where it really looks like it's probably going to threaten South Carolina, we start daily conference calls with all the coastal directors and state emergency management and all the emergency services function (ESF) partners at the state level,” says Baxley.

When the EOC is activated all needed personnel and ESF partners are brought into “the big room.” Zsamar runs the EOC and briefs Baxley, who in turn keeps the sheriff informed. The sheriff is then the one to relay information to local government officials such as the city council chairman and the county administrator. The policy group comes together to decide whether or not to ask the governor to call for an evacuation of the county.

Beaufort County officials work in the EOC during Hurricane Hermine in 2016.PHOTO: Beaufort County Sheriff's Office

Beaufort County officials work in the EOC during Hurricane Hermine in 2016.PHOTO: Beaufort County Sheriff's Office

Key Assets Relocated

The sheriff’s office fields two helicopters, and the local mosquito control element has one helicopter and an OV-10 Bronco. If under threat of a tropical storm instead of a hurricane, like earlier this fall, none have to be relocated.

The key to whether they need to evacuate is storm surge, since Baxley explains the airport was built out of the marsh. During Hurricane Matthew, nearly all buildings at the airport were under water. When needed, aircraft will be flown out to the airport in Columbia to avoid storm surge and any strong winds.

All the sheriff’s office maritime assets are pulled from the water and moved to an open field, slightly more inland near the Marine Corps Air Station, and anchored down. If the storm threat is even more severe, boats will simply be taken over to the Hampton County Sheriff’s Office, 40 miles inland.

Rescue Vehicles

Agencies often pull personnel and regular patrol vehicles off the road when winds reach tropical storm force at 39 mph. However, BCSO is still able to respond with specialty vehicles acquired through the Department of Defense’s 1033 surplus equipment program.

The sheriff’s office has two LMTVs that are used for high-water rescues and four Humvees, two of which are up armored, and several generators. The department also has an MRAP, which weighs about 14 tons Baxley says. Both the Beaufort Police Department and the Bluffton Police Department each also have a Humvee and a high-water vehicle.

“Those vehicles allow us to keep patrolling. So, we pull the Ford Explorers and the Dodge Chargers off the road at sustained 39-mph winds. But then we put officers into the Humvees and we go back out there. And if the National Guard has deployed to Beaufort County, which they usually have, we'll put deputies in their Humvees and we'll continue patrolling as long as we safely can,” Baxley explains.

“It's not a level of response that we would have on a normal day, but it is a continuing response, as conditions deteriorate,” Baxley adds.

During Hurricane Matthew deputies were only off the road for about nine hours, however during Hurricane Irma there was no lapse in response. The deputies just transitioned to the Humvees and LMVTs. Those surplus military assets can make a difference not only in patrolling the county, but also in saving lives.

In one case Baxley shares, a caller reported her spouse was having a heart attack in an area impacted by a four-foot storm surge. An ambulance could not respond into the area, so deputies used a Humvee to transport the heart attack patient back to dry ground and an ambulance. The man survived.

“Had we been five years earlier, there's nothing we could have done for him for probably 24 hours and probably he would not have survived,” Baxley explains.

Hurricane Matthew left damage across parts of Beaufort County, SC.PHOTO: Beaufort County Sheriff's Office

Hurricane Matthew left damage across parts of Beaufort County, SC.PHOTO: Beaufort County Sheriff's Office

Evacuation Improvements

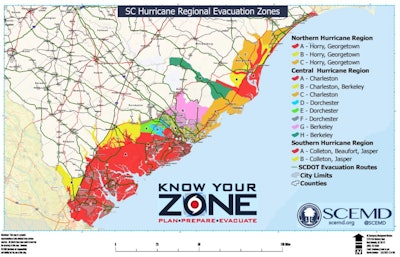

The evacuation plan now in place for coastal South Carolina has its roots in evacuation difficulties ahead of Hurricane Floyd in 1999.

A full coastal evacuation from the Savannah River to Little River on the North Carolina state line was ordered. All the evacuation traffic headed inland and hit choke points all over the place based on the signage that existed at the time, points out Baxley. However, there had been no traffic snarl in Beaufort County, it was all inland.

“It was an absolute disaster where it took 22 hours to drive to Columbia, which is normally a two-hour drive,” he explains.”

As a result, the governor at the time, Gov. Jim Hodges, tapped a state patrol captain who had been out of state on vacation at the time of the evacuation. That person, who did not participate in the evacuation and could take an objective look at it, was appointed traffic czar.

He worked with officials in Beaufort County, and the other counties, to review maps and better understand the traffic flow as it evacuated from the coastal areas. After research and many meetings, that first traffic czar and others realized the best option was to create evacuation routes that would funnel all traffic from the four evacuation zones to Interstate 20.

“Then we took routes that went from the coast to I-20, parallel routes so that they would never have an intersection where they crossed. We came up with seven parallel routes; two routes out of Beaufort County, three routes out of Charleston County, and two routes out of Horry and Georgetown counties,” says Baxley.

“Then we figured out how many traffic control points we had to staff, how many small towns with stoplights or whatever, and it now takes about 3,000 law enforcement officers to make that happen,” Baxley adds.

A lot of resources are tapped to staff evacuation routes. Baxley explains other agencies such as the department of natural resources, South Carolina Law Enforcement Division, the state forestry division, and troops from the National Guard operating under the supervision of law enforcement, are deployed along the evacuation routes.

Signage and state highway maps all have the evacuation routes marked. Baxley points out apps and cell phone maps do not provide the evacuation route. The first big evacuation since the debacle of the 1999 Hurricane Floyd evacuation was during Hurricane Matthew in 2016.

The new plan and keeping traffic flowing parallel to reach I-20 proved to be successful.

Coastal South Carolina is divided into four evacuation zones with all routes leading to I-20.PHOTO: South Carolina Emergency Management Division

Coastal South Carolina is divided into four evacuation zones with all routes leading to I-20.PHOTO: South Carolina Emergency Management Division

“We're now under our third czar, but each one of them came up through the ranks under the one that preceded them and so the plan continues, unabated. We just continue to work on it and massage it. We meet in the spring each year and go over the plan again across the state. Everybody has that opportunity to have an input,” explains Baxley. “I'll stack what we're doing up in emergency management in South Carolina against any of the other 49 states.”

However, according to Baxley, the public is not heeding the evacuation orders like they did years ago. During Matthew there was only about a 50 % response and the following year during the Hurricane Irma evacuation it dropped to about 35%.

Learn More: Essential Strategies for Fleet Preparation and Protection During Hurricane Season

Controlled Re-Entry

“After every major storm of the past, I guess going back to Hurricane Andrew, we have made it a point sometime in the six to eight months after the storm to pay a visit to the impacted area, talk to law enforcement, talk to the emergency management directors, and get their honest lessons learned,” says Baxley.

Hurricane Katrina hit Louisiana in August 2005. Baxley recalls when he visited the area months later, in October, he still had to pass through numerous checkpoints. You had to have the right pass or credentials to go through those checkpoints.

“I took all this in, I took pictures, I took notes, and came back and we built a plan based on what we saw there and what we saw in Monroe County, FL, down in the keys,” he explains.

Beaufort County’s reentry plan allows those doing search and rescue and saving lives to return – that means law enforcement, fire, and EMS basically. The Incident Re-Entry Pass System prioritizes public safety workers as tier one, essential personnel as tier two, and support personnel as tier three. The fourth and final tier is for businesses, residents, and property owners. Passes are renewed every two years for those who qualify.

According to the department, first responder personnel, who are directly affiliated with the response efforts of Beaufort County, are not required to carry Incident Emergency Response Passes. But they must be in uniform and have their proper agency and/or law enforcement credentials.

Requests for Incident Emergency Response Passes and Incident Re-Entry Passes will only be accepted from Jan. 1 through April 30 of each year. They expire after two years.

Beaufort County is comprised of multiple islands and that may make it more difficult during evacuation, but the flip side is return access is very easy to control. Re-entry points, for the entire county, can be sealed with just seven checkpoints.

The general public is only allowed to return when one key element is in place and operational.

“We have two hospitals in the county and a third hospital in Jasper, right outside of the county, that services Beaufort County. We have to have an operating emergency room before we'll let the general public come back in,” Baxley says.