Over the past 12 months, our country has felt the impacts of the “Defund the Police” movement – and now it seems, we are at an impasse on what comes next. Congress failed to pass a bipartisan police reform bill last fall, and municipal leaders who made aggressive decisions to defund law enforcement efforts without a plan for what came next are now backtracking. The debate has been over-simplified and politicized by both sides of the aisle.

Opinion: In the Post-Defund the Police Era, Restoring Public Safety Requires “Precision Policing”

Our nation’s law enforcement officers are faced with new challenges and are expected to perform as if these challenges do not exist, on even tighter budgets. That is why we’ve adapted the Precision Policing framework to today’s reality by launching Precision Policing 2.0.

Now that advocates from each side of the divide have had their day, and given the rise in violent crime nationwide, we must put politics aside and band together to hold common-sense conversations about the public safety solutions needed to best support modern police departments. This means that America’s policing strategies must be dynamic enough to meet the realities of the 21st century – increasing accountability, developing robust programs to support officer wellness and training, and implementing technology to streamline and improve how agencies operate.

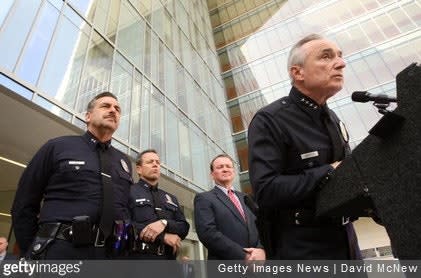

As Police Commissioner of the New York Police Department and Chief of Police of the Los Angeles Police Department, I guided and witnessed the positive results of a realigned policing model that bridges the police-community divide –working as partners, not adversaries in the communities that need it most to drive down crime rates. The common-sense approach we launched in New York City, and had great success with, we called “Precision Policing,” a wholistic strategy focused on data analysis, neighborhood coordination, and non-enforcement intervention.

But today, our nation’s law enforcement officers are faced with new challenges and are expected to perform as if these challenges do not exist, on even tighter budgets. That is why we’ve adapted the Precision Policing framework to today’s reality by launching Precision Policing 2.0.

Over the last year, I worked with a team of current and former police department leaders, community anti-violence leadership and the University of Cincinnati’s Public Safety Research Center to publish a white paper outlining the key principles and practices of this strategy. It is a step toward police reform needed nationwide.

To help resecure community trust and accomplish the stated priorities of most social justice advocates, police departments will require strategic, pinpointed increases in funding, not fewer financial resources. Instead of cutting off funding or allowing police leaders to direct their resources to securing advanced weapons and vehicles often deployed by frontline soldiers in warzones, tax-payer dollars should be geared toward tactics that benefit communities including data tracking systems, crime reduction-technology, expanding incident reviews, officer mental health programs, and implementing training courses – including for de-escalation. Precision Policing 2.0 can provide a critical framework for police leadership to deploy those expanded resources geared at rebuilding public confidence and safeguarding our communities more effectively.

The Four Pillars of Precision Policing

First,evidence-based crime and disorder prevention. Data shows that most crimes occur in concentrated areas by a small number of offenders. If police can zero-in on these perpetrators and hot-spot areas, they can develop a systematic analysis of the crimes and thus tailor their response. Today, technology makes it easier to access the latest data and research to determine if crime and disorder prevention strategies are effective, and then initiate new research if not enough evidence exists to support a strategy.

Second, community engagement and protection. When officers and community members work together, trust begins to be restored. The many ways to drive engagement include community meetings, strategic advisory groups, and ad hoc community input. This can be as simple as having an officer walk through a neighborhood, reminding community members to lock their doors and cars if there has been an uptick in break-ins.

Third, transparency and accountability. Rebuilding community trust in law enforcement requires transparency and accountability so that citizens know that police officers are operating appropriately and that they are responsible for their actions. Ways to achieve this include local government review, open data, body-worn cameras, incident reviews, and public policies.\

And finally, officer performance, safety, and wellness. The official motto of many departments is “To Protect and to Serve.” That starts with officers maintaining a healthy frame of mind both on and off duty. Most of the issues brought forth by defund supporters can be directly tied to gaps in funding for officer training. While all officers receive basic training at the Academy, most are not given the opportunity to take additional instructional courses throughout their career – including critical de-escalation training needed to combat the gun violence epidemic. Access to adequate financial resources would allow police leadership to implement advanced training programs for experienced officers – including training to improve police with our more vulnerable community members, including the homeless, those with mental disabilities, and those impaired by narcotics.

While law enforcement in the United States has been evolving for the last 50 years, we still have a long way to go to fully meet the needs of our modern society. I would argue that we have little choice but to seek the improvements offered by the Precision Policing 2.0 strategy. Now more than ever, law enforcement agencies must have access to the resources needed to implement strategies that have proven successful to improve the safety of our dedicated officers and reestablish trust with those they are sworn to protect.

William J. Bratton served as commissioner of police in New York City (1994 to 1996 and 2014 to 2016) and Boston (1993–1994) and chief of the Los Angeles Police Department (2002 to 2009). He is co-author, with Peter Knobler, of “The Profession: A Memoir of Community, Race and the Arc of Policing in America.”

More Blog Posts

Preventing Heat Injury in Police K-9s

In the relentless heat of summer and even early fall in some parts of the country, officers face the important task of protecting their K-9 partners while working in sweltering temperatures. Recognizing changes in a dog’s behavior is the key.

Read More →Why Your Agency Needs to Attend the ILEETA Conference

ILEETA is a complete resource for trainers to address trainers' needs. Its mission is to enhance the skills and safety of criminal justice practitioners while fostering stronger and safer communities.

Read More →IACP 2023: New Training Products

Technologies for improving law enforcement training and training management were some of the highlights at this year's show.

Read More →Initial Results Released from MSP 2024 Police Vehicle Testing

The 2024 pursuit-rated vehicles--all pickup trucks or SUVs, including two battery electric models the Chevrolet Blazer EV AWD and Ford Mustang Mach-E--were put through their paces.

Read More →Officer Safety Considerations Related to Alternative-Fuel Vehicles

As more alternative-fuel and hybrid vehicles hit the road, police and other first responders need to understand that they are no more dangerous than conventional vehicles. However, there are certain safety considerations every cop should know.

Read More →Garmont Working to Grow LE Market Presence

Garmont Tactical has found wide acceptance by military boot buyers, but now the company is trying to better respond to the needs of police officers. Many cops now are not fans of 8-inch boots, so Garmont is adapting.

Read More →Publisher’s Note: Our Commitment to You

Through our magazine and website and our Police Technology eXchange event, we promise to provide you with information and access to resources to help you do your job safer and better.

Read More →10 Tips for Responding to Mental Health Crisis Calls

The Harris County Sheriff's Office is a model for other agencies that want to learn about crisis intervention and mental health crisis response. Sgt. Jose Gomez shares the story of their programs and provides 10 tips for mental health crisis call response

Read More →5 Things to Know When Buying Concealed-Carry or Off-Duty Holsters

Mike Barham, of Galco Holsters, shares five important considerations to keep in mind when you buy off-duty concealed or plain-clothes carry holsters.

Read More →10 Tips for Reviewing Use-of-Force Reports

While the burden of accurately reporting use-of-force situations is on an individual deputy or officer, the person reviewing those reports shares in the responsibility of making sure the reporting is done properly, with clear details included.

Read More →