Training simulators see widespread use in law enforcement today, but they have grown to be more than just a shoot/don’t shoot drill. The true value of immersing officers into a simulation now is far more impactful, whether teaching officers de-escalation or improving their communication skills with fellow officers.

Best Practices for Training with Simulators

Simulators are no longer just firearms practice for officers. The provided courses can teach duty to intervene, de-escalation, dealing with mental health calls, even facing infectious diseases, or interacting with individuals on the autism spectrum.

Modern training simulators allow use of red dots and other sight systems.

VirTra

How departments use training simulators can vary widely, but the main objective should always be to use, or design, simulations that are matched to the training needs of the agency.

Training Objectives

“I've dealt with certain organizations that would like to use this for nothing more than getting judgmental decision-making on the use of force. I get other organizations that want to use it as a full-on training tool. So, it's going to come down to the organization and what their needs are,” says Steve Holmes, a trainer at Ti Training.

Lawrence Kehoe, training content specialist at MILO, points out that many departments simply invest in a simulator and then never use it to its full potential. He stresses officers need to be trained on a broad range of skillsets and scenarios to get the best value from the investment.

Simulators are no longer just firearms practice for officers. The provided courses can teach duty to intervene, de-escalation, dealing with mental health calls, even facing infectious diseases, or interacting with individuals on the autism spectrum.

“The utilization of the simulator is far more than shoot/don't shoot, if it's being done, right,” says Lon Bartel, vice president of training and curriculum for VirTra.

Some training content has now been developed to include the chain of command between officers and supervisors. The supervisors may be in the simulation, or might be off set and in communication with the officers in the scenario.

“They'll pull the supervisor in, and they will say, ‘OK, now your officer has been involved in this situation, what are your responsibilities as a supervisor for making sure that all the necessary responsibilities are taken care of on that scene?’” explains Holmes. “So, they're basically teaching their supervisors what they need to be doing and how they need to be communicating during possible critical incidents.”

How does a department determine what those other training options should be? They can be varied. First, look at what training is needed within the department and then devise training, including simulator sessions, around those departmental goals.

Holmes says he tells police departments to review their use-of-force incidents, their critical incidents, possible policy violations and things of that nature, and then draw from their experiences and past training to craft where the agency needs to go with simulator training.

“I don't think there's any career in the world where you're asked to do so many different things, and you're expected to be perfect at every single one,” explains Kehoe. “Sometimes you physically need to control people, you need to fight, then you're a social worker five minutes later, and then you're taking care of a small child, and then you're doing CPR, and then you're doing crisis intervention. You could be doing all that within a few hours. You have to have a well-rounded training regimen for your agency just because you don't know when each incident will occur. You have to be ready for all of them.”

Instructor Prep

The instructor, or trainer, drives the simulation and must gauge it both to fit the level of the specific trainee/officer and at the same time achieve the departmental training goals. The role is one of crafting a game plan, challenging the trainee, stepping in to coach as needed, and following with a good debrief to help the trainee learn.

“I acknowledge that the only absolute about human performance, is it varies. Somebody could just be having a bad day. But as a coach, it's my responsibility even on their bad days to get the best performance out of them,” Bartel says.

He suggests approaching training as a crawl, walk, run progression – challenging the officer just enough, but keeping the scenario and stimulation to the appropriate level of where they are along that continuum.

It is crucial for the instructor, according to Holmes, to have clear goals and objectives put into place and make sure they have a strong understanding of the subject material prior to starting the simulation. He also suggests instructors should reinforce positive behaviors they see in the trainees.

Amanda Williams, cognitive division manager at MILO, points out the instructors need to become familiar with each scenario and know the various branches and all the outcomes before running the simulations for trainees.

“Just fire up the system and sit at the desktop or tablet and you can play it through and just click each branch and see what the outcomes could be,” Kehoe suggests. “Spend time and have a plan.”

An instructor monitors a trainee's interaction during a simulation.

MILO

Simulation

Every good instructor running a simulation knows the trainee must be challenged, and through that learn.

“How I give you your prebriefing really helps me as the instructor to drive that arousal in your sympathetic nervous system,” says Bartel. “If I want to raise you up a bit, less time/more info; go. If I want to bring it down, I give you the info, maybe I'll hand it to you on a card, you can read it, you can ask questions. And again, where are we on the crawl-walk-run spectrum with this particular trainee?”

Bartel expects to see heart rates and respiration rates rise and the trainee’s voice may increase in both volume and pitch. Those are all indicators he has achieved sympathetic arousal in the trainee. The key now is to make sure that arousal is at the correct level to challenge but not overwhelm.

“You've got somebody who's a brand-new recruit and possibly never even handled a firearm, never been involved in some kind of a critical incident, or even a debrief; you're going to handle them differently than you're going to handle a 20-year veteran of a police department,” explains Holmes.

As the simulation progresses, the trainer listens and then adjusts the scenario based on the trainee’s approach. Maybe it's a new officer, so there's definitely a route that you could go down, that would be more applicable to building their confidence and building on the things that they're doing, right.

“You don't help them,” says Kehoe. “You let them figure it out on their own, and then try a different approach. So that alone is stress-inducing, but then that's where they learn because they're now attempting a new approach that they hadn't previously thought of, so maybe next time when they're out in the real world, they can try that other thing. And maybe that's the key that unlocks it and what makes it work.”

As an instructor, Kehoe says he wants to amplify that stress level in training and points out mistakes can surface in a simulation rather than in a real-world scenario out on the streets. But training in a simulator is not just about making mistakes and learning from them.

“You want to build on the wins. That's the important part. You want to really pump up and build confidence on the things that were done well, because attitude is a huge part of it,” Kehoe adds.

Training simulations can involve the use of a variety of weapons, less-lethal options, or no weapons at all.

MILO

Pause

While some trainers prefer to let trainees work through resolutions of anything they face in a simulation, there are times when immediate intervention is needed.

“You can also have the instructor in the middle of it pause and start using some type of Socratic questioning so that we don't have people fail at a specific juncture and then compound the failure because we keep letting them go. The first moment of a mistake, pause,” suggests Bartel. “You can literally correct the behavior at the earliest possible convenience in a simulator.”

He provides the example of someone making entry from a doorway. As they pie the corner, they take a huge step with their right foot as they're moving, left to right, to a point where that would literally be a target indicator to a threat in the room.

“Pause! That is such a severe mistake that I don't want to let it continue on. They’re at crawl stage still,” says Bartel.

In this situation, the instructor would lead the trainee through breaking down how he approached that threshold evaluation and looking for threats. As the officer scans for outlines, body parts sticking out, etc., what is the severity of his exposing himself to a threat? In the real world, an officer would want to mitigate his body sticking out. Did he do that?

The trainee gains a memorable learning moment when the instructor leads the student through this discussion.

Williams likewise sees some errors can be glaring enough for the instructor to hit the pause button, but an alternative is to tag the error and address it later in the debrief. The choice would be in the hands of the instructor.

“Well, let's say they put their finger on the trigger too early, you can tag that and ask, ‘why did you do that?’ You can pause it and ask them, or you can ask later when they're finished,” says Williams.

Debrief

The training scenario is over, and whether an instructor paused the simulation or not, it is now time to continue the learning during the debrief. This is where the ability of talented instructors can shine as they tactfully lead the trainee to discover what they need to learn from the just-completed exercise.

“The most valuable part of this is the debrief after, what the officer is going to take out of it, and what they're going to either learn from what they've done right or what they may have potentially done wrong,” says Holmes. “Usually, you want to leave it a little open ended. So, you give the officer an opportunity to speak and explain why they did what they did, how they observed what they did, and talk about what their reasoning was for why they did what they did.”

The debrief typically starts with simple questions. “What did you see, what did you hear?”

“That question tells me as the instructor what their arousal levels were,” points out Bartel, explaining that a trainee’s answer could include a few items or as many as 15 or more. Was the arousal level so high that they focused on one element, but missed others?

Next, the instructor may ask something like, “What did you do, and why?”

“This is where the preconceptions start to come out,” says Bartel. “And those preconceptions that could be wrong are devastating in law enforcement.”

Time in the simulator is all about choices. The instructor during debrief can question those choices while guiding the trainee to self-discovery of what they did, did not, or maybe should have done. More importantly, the trainee must learn to articulate why they did or did not do something.

“As the instructor, I'm not going to give you the answer. I'm going to question you into your own discovery of where you may have made a mistake, or could have improved, or whatever else it is. And that takes a lot more practice, a lot more time,” Bartel explains.

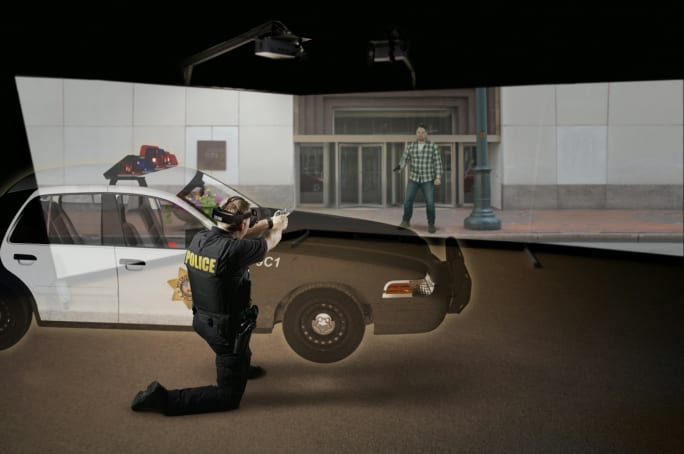

Simulators that allow officers to move, or take cover, add to the realism of the scenario,

Ti Training

Use It

Some departments purchase training simulators and for whatever reason may not use them as much as planned or may use them in just a narrowly limited type of training. There can be scheduling challenges to get officers, or trainers, in for the simulations. Maybe the trainer who was the one to spearhead the simulator focus has now moved on or retired. Whatever the challenges, don’t let the investment go to waste.

“Utilize it as frequently as you can and utilize it to its fullest potential. Don't go in and treat it like a video game. Make the officers take it seriously and give the understanding that so many of these scenarios that we're dealing with in here come from real world experiences,” recommends Holmes. “Instill in the officers as they're going through it that these experiences have happened to other people and it could potentially happen to them, so learn from the experience.”

“I always say, with this, the sky's the limit. It comes down to your creativity as an organization and what your goals and objectives may be,” he adds.

More Patrol

Safariland Solis Rethinks Concealable Duty

What if Level I retention didn’t require a full duty rig? Safariland’s Solis delivers trusted ALS security in a streamlined OWB platform built for administrative and plainclothes professionals who need protection without the bulk.

Read More →

K-9s Play a Critical Role in Finding Missing Persons

Real-world scenarios show that a tracking canine can detect and follow a human track several hours after it was made.

Read More →

Garmont Tactical’s LE Boot Lineup

In this video, we get a look at the latest law enforcement boots from Garmont Tactical, both for men and women. Kyle Ferdyn, sales manager, showcases four of the latest boots.

Read More →

Avon Protection Launches EXOSKIN-S2 High-Performance CBRN Protective Suit

With the commercial availability of Avon Protection’s EXOSKIN-S2, users now have increased options for their protective suit requirements across the spectrum of CBRN threat environments.

Read More →

Versaterm Acquires Aloft to Unlock a New Era of Drones for Public Safety

Versaterm has acquired Aloft, an FAA-approved Unmanned Service Supplier (USS) that specializes in real-time airspace intelligence and flight authorizations.

Read More →

Versaterm Launches Innovation Summit for Public Safety Drone Operations

The two-day DroneSense Innovation Summit by Versaterm will bring together public safety and industry experts to define best practices for scaling drone operations.

Read More →

What Makes a Good LE Boot?

Learn what makes a boot good for police officers as POLICE visits with Kyle Ferdyn, of Garmont Tactical, who explains the features of boots and why each is needed in an LE boot.

Read More →

Folds of Honor Opens Scholarship Application for Children and Spouses of Fallen or Disabled Service Members and First Responders

The application period for the Folds of Honor scholarship program is now open through the end of March. Scholarships support students from early education through postsecondary studies, easing the financial burden for families who have given so much in service to others.

Read More →

Team Wendy Now on GovX: Faster Verification and Discount Access for Eligible Professionals

With GovX verification now integrated directly into the Team Wendy checkout experience, eligible customers can confirm their status in just a few clicks and have the discount applied automatically.

Read More →

5.11 Debuts 2026 Footwear & Apparel at SHOT Show

5.11 showcased new apparel and footwear products during SHOT Show 2026, including new color options for the A/T Boa Lite Mid Boot and the Founder’s Jacket.

Read More →