Every year the FBI publishes statistics for those officers who died in the line of duty the previous year. It includes data on officers killed both feloniously, and not.

It is a great tool and it validates and underscores the need for sound officer safety practices.

But it only gets part of the story.

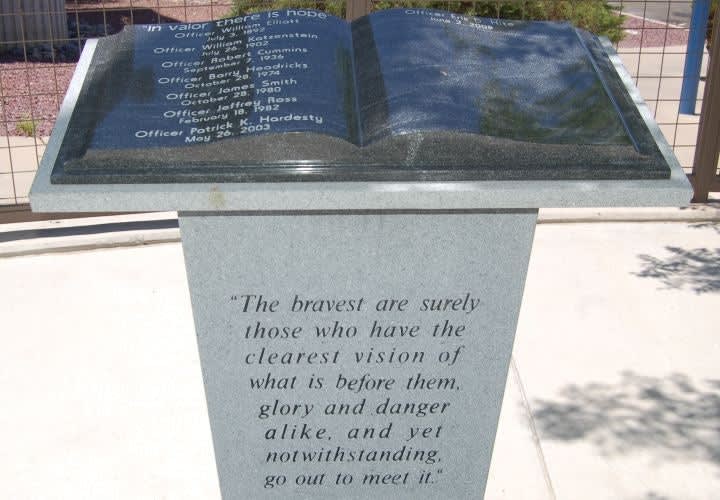

And the same is true about the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial. Every year names of officers killed in the line of duty are engraved into this beautiful Washington, D.C. memorial.

But you and I both know that many officers' names are missing. We've worked alongside them and we've seen them fall.

One has to wonder how many officers have been victimized on multiple fronts. Not just by the acts of assailants in-house and out, but by their subsequent injuries not being recognized as duty-related by the usual bean counters and paper-shufflers. How many of them have then ultimately succumbed to such injuries without their deaths being recognized as duty related?

And what of those whose deaths may or may not have been duty-related?

I can't help but think of two Los Angeles County Sheriff's deputies who worked at Temple Station. They both died of brain cancer in the prime of their lives. Coincidence? Perhaps. Certainly the L.A. County Sheriff's Department concluded as much despite the fact that the two men had worked a hazardous material spill in South El Monte a few years before.

How many cops have unwittingly been exposed to all manner of contaminants while ensuring the safety of others, diverting motorists and pedestrians alike from fire and accident scenes, all the while having ingested the kinds of substances for which those little warning placards are developed? And has every cop whose respiratory system was compromised while checking out a chemical warehouse or meth labs been covered?

What about the cops who perhaps didn't crash and die on their way home from work after working 24 hours straight only to run an errand the next day and get killed in a car crash because of fatigue?

And what about those who have seen too much pain and suffering and taken it too much to heart.

For every cop killed feloniously, there are three killed by their own hands. I think of Oklahoma City sergeant Terry Leakey who saved several lives in the aftermath of Timothy McVeigh's terrorist act but was unable to save his own. I think of a deputy I worked with who was one hell of a street cop and possibly the best dispatcher in LASD's history who, like so many other cops, killed himself shortly after his retirement. I think of the deputy who helped exposed a cover-up, only to blow his brains out in the station parking lot after years of ostracism and ridicule from his peers thereafter.

There are other threats — some that are not just endemic to our profession; some just now becoming known. Skin cancer has long been recognized as a dayshifter's bane. Recent studies have found higher rates of breast and prostate cancer among women and men who work night shift.

Yes, the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial is a laudable entity and is a most honorable way to acknowledge those whose deaths have been recognized as being in the line of duty.

But let's not forget our other brethren who work may have been less conspicuously gallant, but who have likewise paid the ultimate price years before their time.