Pointing out that the purpose of Miranda procedures is to neutralize the compulsion felt by a suspect in custody facing obvious police interrogation, the court said that an undercover situation does not present this same risk of coercion, since the inmate is unaware he is talking to the police:

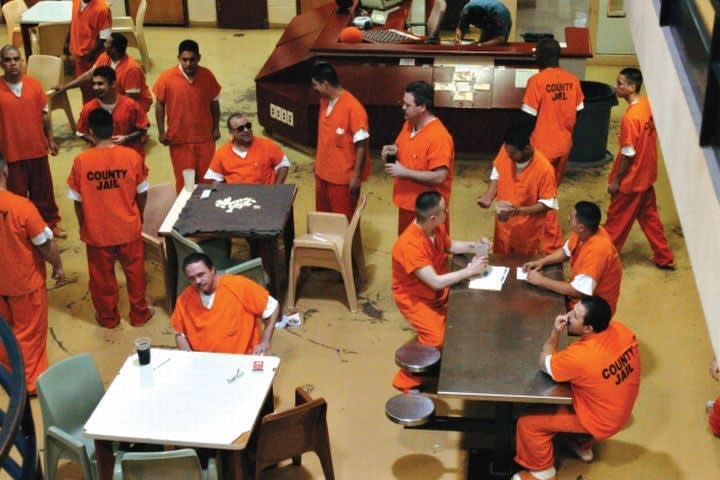

“The use of undercover agents is a recognized law enforcement technique, often employed in the prison context to detect violence against correctional officials or inmates, as well as for the purposes served here. The interests protected by Miranda are not implicated in these cases, and the warnings are not required to safeguard the rights of inmates who make voluntary statements to undercover agents.

“We hold that an undercover officer posing as a fellow inmate need not give Miranda warnings to an incarcerated suspect before asking questions that may elicit an incriminating response.”

Applying the ruling of Perkins, other federal courts have also upheld the practice of using undercover agents to conduct unMirandized interrogation of inmates. In a federal case in Iowa, the U.S. Court of Appeals pointed out the obvious: If the undercover agent had to give the Miranda warning before conversations began, “the whole purpose of the undercover operation would be destroyed.” (U.S. v. Johnson) In a Wisconsin case, the Court of Appeals noted that, “Planting informants is not an unconstitutional method of collecting evidence for use in criminal trials.” (U.S. v. Kontny)

State courts, too, have applied the Perkins rule, e.g., People v. Williams (California), Norrid v. State (Texas), and Commonwealth v. Boggs (Pennsylvania). Some states refuse to follow the U.S. Supreme Court rule, citing state constitutional due process or self-incrimination grounds under which criminals may be given greater protections than under the federal constitution. See, e.g., Walls v. State (Florida). Before using the Perkins technique, it is advisable to check with a local prosecutor or legal advisor in your jurisdiction to be sure there are no limitations imposed as a matter of state law.