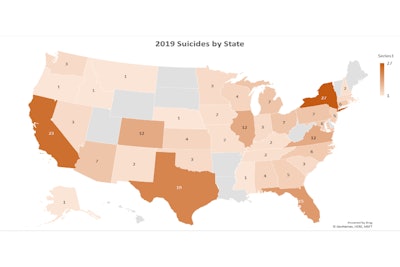

In total, 39 of the 50 American states suffered at least one police officer death by suicide in 2019.Image courtesy of Blue H.E.L.P.

In total, 39 of the 50 American states suffered at least one police officer death by suicide in 2019.Image courtesy of Blue H.E.L.P.

For the fourth consecutive year that such data has been collected, more American police officers have been reported to die by suicide than all other line-of-duty deaths combined.

According to data released by Blue H.E.L.P.—an organization that tracks police officer suicides while simultaneously seeking to prevent such tragedies from occurring—228 American police officers died by suicide in 2019.

By comparison, 132 police officers were killed in the line of duty this year.

Gunfire was the leading cause of line-of-duty deaths, with a total of 47 officers feloniously murdered in this way. Vehicle incidents caused 45 deaths in 2019. Sixteen officers died by heart attack and 11 succumbed to 9/11 illness. Other causes of death included drowning, heat exhaustion, and training accidents.

This is a substantial decrease in duty deaths in comparison to previous years—indeed, a decrease of 20% compared to 166 in 2018, 175 in 2017, and 175 in 2016.

While duty deaths declined in 2019, the number of reported police officer suicides—including active-duty and recently retired—increased significantly. Compared to 228 in 2019, there were 169 reported suicides in 2018. The number of reported suicide deaths was 168 in 2017 and 143 in 2016.

Demographic Data

Of the officers who died as a result of suicide in 2019, approximately 90% were male and 10% were female.

Veteran officers with between 20-25 years of service were most susceptible to suicide, with 59 deaths in that demographic segment.

The overwhelming majority of officers to die by suicide in 2019 were Caucasian, with 187 suicide deaths among whites. Twenty reported deaths were Hispanic and 13 were African American.

The state of New York had the highest number of deaths by suicide with 27, followed by California with 23 and Texas with 19 police officer suicides. Florida reported 15 deaths by suicide.

In total, 39 of the 50 American states suffered at least one police officer death by suicide in 2019.

Continued Analysis

Although there appears to be an increase in police officer deaths by suicide, the numbers reported here do not necessarily indicate an increase in suicides. They do, however, indicate an increase in reporting to Blue H.E.L.P.

Karen Solomon, co-founder of Blue H.E.L.P. said, "While it's disheartening to see these numbers rise, we can't be sure that suicides are on the rise or if they are being reported more accurately. We've been lucky to have the support of the families and departments, they've been in contact almost immediately after a suicide for support and to let us know about their loved ones."

Solomon added, "We are looking forward to reducing these numbers in 2020, offering more support to the families and continuing to raise awareness. Blue H.E.L.P. is devoted to this cause and we are grateful for the outpouring of support, domestically and internationally, we have received."

Blue H.E.L.P. co-founder Steve Hough said, "As 2019 closes, we are thankful for those who have taken the time to report officer suicides across the nation. We at Blue H.E.L.P. understand the importance of maintaining these statistics and will continue urging others to report information."

Hough continued, "In 2019, Blue H.E.L.P. collected more data than any previous year which indicates their families, friends, and co-workers are willing to move beyond the stigma of suicide and mental health to provide us data which may help others in the future."

Blue H.E.L.P. is the only organization in the country that collects law enforcement suicide data and regularly supports families in the aftermath. Individuals and agencies can report the tragic suicide deaths of officers at the Blue H.E.L.P. website.

2020 Vision

"They say hindsight is 20/20," said Jeff McGill, Blue H.E.L.P. co-founder. Blue H.E.L.P. wants 2020 to be the year of hindsight for law enforcement officers, agencies, and supporting organizations. 2020 should be the year that we look back and realize that suicide is the biggest threat we face and we should respond accordingly

Moving into the year 2020, Blue H.E.L.P. plans to prioritize sharing information about the ways in which officers and organizations are working to prevent police officer suicide.

"Unfortunately, Blue H.E.L.P. has become the bearer of bad news, reporting on the numbers of deaths by suicide," said BlueH.E.L.P. public relations advisor Doug Wyllie. "It's time to take it to the next level and start telling the stories of officers who sought out and received help to resolve their crisis as well as agencies that have worked to remove the stigma of getting that help."

"Success stories need to be told—they exist, and they can help police officers, agencies, and organizations continue to change the culture in law enforcement in positive ways," Wyllie added.

In 2020, Blue H.E.L.P. will continue to seek out success stories of resilience and survival.

In 2020, Blue H.E.L.P. will continue to improve the availability of mental health resources for officers across the country and to normalize the treatment of post-traumatic stress symptoms.

In 2020, Blue H.E.L.P. will continue to provide unprecedented support for families who lose an officer to suicide including retreats, honor dinners, and emotional support.

If you or someone you know has ideation of suicide or is approaching crisis, please know that the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (1-800-273-8255) provides 24/7, free and confidential support for people in distress. Safe Call Now (1-206-459-3020) offers those services specifically for first responders.

On a website maintained by BlueH.E.L.P.—an organization that tracks officer suicides while simultaneously seeking to prevent such tragedies from occurring—a first responder need only enter a few data points—such as their location and what kind of assistance is needed—and the individual will be provided with a list of options for help from a searchable database dedicated to helping first responders find emotional, financial, spiritual, and other forms of assistance.