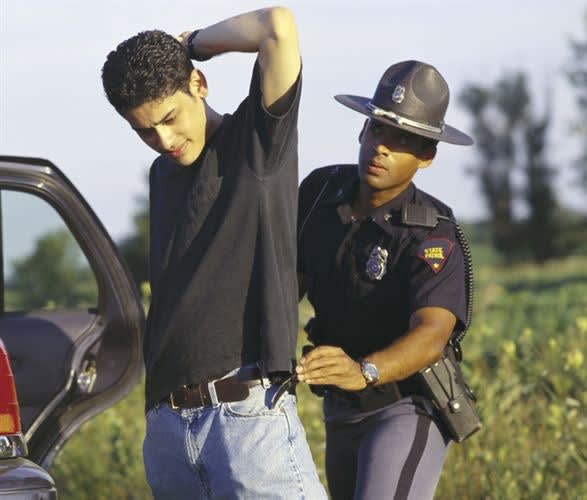

Patting down a suspect is serious business and you can never be reminded enough of the hazards of doing it poorly.

Some of you reading this article may immediately shut down, thinking, "I'm a veteran cop. I know everything to know about searching suspects." But I'm here to tell you that attitude can get you killed. Patting down a suspect is serious business and you can never be reminded enough of the hazards of doing it poorly.

One of the major causes of line-of-duty deaths among American law enforcement officers is the presence of undiscovered weapons on suspects. Here are just a few examples of tragedies that have resulted from poor searches:

Two state troopers were murdered by a drunk driving suspect after they removed his handcuffs to administer a breath test. The officers had missed a handgun concealed on the man's person.

A patrolman was killed by a pistol shot fired from the back seat of his patrol car by a prisoner he had searched inadequately before transporting.

An officer was slain in a jail cell while preparing a prisoner for transport to another holding facility. From his clothing the inmate produced a handgun that had apparently been missed by multiple searches.

In an era in which virtually every peace officer has been exposed to the vital principles of officer safety, no member of our ranks should die at the hands of someone who should have been safely in custody. Yet, as the preceding examples reveal, it does happen. And most of the time, the means of the officer's death was present because of an inadequate search of the person in his custody.

Safe Searching

Regardless of the type of search you are carrying out, several cardinal rules apply.

First, whenever possible the search of a person should be carried out under the watchful eye of a cover officer. It is this officer's responsibility to come quickly to your aid if resistance develops. In addition, the second officer provides psychological deterrence and may prevent trouble from developing.

Second, officers normally should follow the principle of "handcuff first, search second" when taking an individual into custody. Although special circumstances call for special responses, the fact remains that an individual who is properly secured by handcuffs is less likely to hurt the searching officer. But remember, handcuffs are temporary and fallible restraints that can be (and have been) defeated, and great care must be exercised around handcuffed people.

Third, searches of people, even so-called "pat down" searches, should only be executed by an officer wearing protective gloves. There are a number of good patrol gloves on the market that feature material to shield against lacerations and pricks by blades and needles and protection against body fluids. The key is to choose gloves that offer some degree of protection yet are not so thick and bulky so as to make it impossible to feel weapons and other items through them.

Fourth, before beginning any search, ask the subject if he has anything on him that could get him into trouble. He should be asked specifically if he has needles or blades. One veteran street cop I know uses the same speech to accompany every search: "I need to know if you have anything on you that might hurt me. If I get hurt by something you said wasn't there, we're both going to be sorry." That's all he says. The subject is left to decide for himself the officer's meaning. Of course some people will lie and only a truly foolish officer would throw his searching caution to the wind after being assured by a street mope that he is "clean."

Fifth, it is worth remembering that not everything that looks innocent truly is. Survivalist magazines and catalogs are full of ads for cutting instruments and firearms disguised as pagers, ballpoint pens, belt buckles, credit cards, and other benign items. (For more on these disguised weapons, see "Hidden Threats," Police, August 2002.)

The best way to avoid becoming a victim of such a weapon is to let your imagination run wild when it comes to examining the items carried by the subject you are searching. For example, all neck chains may have a stabbing or slicing device at the end of them. All belts may conceal a stabbing instrument or handcuff key. Check them carefully.

Finally, every law enforcement officer should realize that there is no magic number of times that a person should be searched. An individual who is taken into custody should be searched immediately upon his physical arrest, searched again before being placed into a vehicle for transport, and searched yet again before being taken out of handcuffs for booking and incarceration purposes.

Generally speaking, each search should be more detailed than the last. But you must rely on your own common sense and safety judgment to tell you if still more detailed searches are needed.

"Pat Down"

The terms "frisk" and "pat down" are not particularly accurate in describing the technique of searching a suspect, as they tend to give the impression that the search is perfunctory. Don't ever take a search so lightly.

To perform a good pat-down search, let the subject to be searched know what you expect of him. Announce your intent to search in clear terms. What's said will vary from one situation to the next, but many officers simply state in a firm but courteous fashion, something like, "I just need to check you for weapons here. Turn around and face away from me. Spread your legs and interlace your fingers atop your head for me, please.

Different subject control systems put different "flourishes" on what happens next. In one often-used technique, the officer approaches the subject from the rear to within touching distance and grasps the person's interlaced fingers with his weak hand. The subject is then arched and pulled backward somewhat so that if resistance occurs the individual can be pulled quickly to the ground while the officer backs off to produce whatever force option appears indicated by the threat level.

The idea is to pull the subject back enough so as to have him off-balance. While the subject's fingers are clasped with your weak hand, reach around with your strong hand from the subject's rear and search that side of his body. Clothing is patted and gently squeezed for anything that appears out of place. (Hopefully, you have already visually scanned the party for any out-of-place bulges or visible weapons, such as a knife in a scabbard or a holstered handgun.)

Complete the search down the entire side of the subject's body, working from his head to feet. When the search of that side is complete, switch hands without losing control of the subject. You should now be using your strong hand to clasp the subject's interlaced fingers while your weak hand checks the other half of the subject's clothing and person, front and rear. Any weapon or other dangerous item encountered should be removed and secured in your belt. The search then continues for additional threats.[PAGEBREAK]

Full Custody Search

Anyone taken into custody for any reason must be searched. That's rule number one of the arrest process.

Many of the precautions and techniques of the "pat down" search apply here, too. But the position of disadvantage in which the subject is placed may vary, as some felony or high-risk arrest tactics call for the individual to be proned out or directed to kneel, at least initially.

Regardless of the subject's position, work from the subject's rear under the surveillance of a cover officer. Once again, be careful to keep your own balance by not reaching too far around the subject. But keep the subject off-balance throughout the process. And always remain alert for a sneak attack from even the most "compliant" individual.

Every full custody search is conducted systematically. The search targets are weapons, evidence, and contraband. Begin the search with the subject's headgear and hair and progress downward to his or her feet. The inside and outside of a hat or cap should be checked, as should the subject's hair. Remove jackets and other overgarments (coats, sweaters, vests, etc.) and check all shirt collars. A thorough search proceeds inward from the outer garments to those closest to the skin.

Pay very careful attention to chains or cords around the subject's neck. Always remove them and check for any attachments such as razor blades.

While keeping an eye on the individual for obvious irregularities, such as bulges under clothing, run your hands along the outside of his or her clothes. Empty the pockets. Pat folds in the clothing and squeeze them gently to probe for hidden items.

Now continue down the subject's front, sides, and back. Pay special attention to the armpits, small of the back, and groin area. Experience has demonstrated that the groin is often one of a veteran criminal's favorite hiding places for weapons or contraband. He assumes that many officers will be reluctant to search closely in the crotch of another man's pants.

Inventory and bag the items recovered during the search and place them out of the subject's reach. Separate the subject from all pocketknives, pens, lighters, belts, ties, keys, medications, and footwear. Be sure to check shoes and boots for hidden compartments or weapons. The contents of wallets should be tallied, not only to protect the officer from allegations of theft but also to reveal hidden razor blades, needles, and bindles of drugs.

And don't ever rush through the search process. It simply will take as long as it takes to do the job right. Your life could depend on it.

Every officer who assumes custody of a prisoner is wise to search him anew, no matter how many times he may have been searched before and in spite of another officer's pronouncement that he is "clean." Not every officer is as careful with searching techniques as you should be.

Getting Personal

While beneath-the-clothing searches normally should be executed by an officer of the same gender as the person being searched, that does not preclude an arresting officer of the opposite gender from conducting a pat down for weapons. Remember, there is a big difference between a pat and a grope.

Likewise, the officer who has arrested a member of the opposite sex is not precluded from promptly retrieving a hidden weapon which he or she has good reason to believe is present. In addition, purses, handbags, and fanny or waist packs must be placed beyond the reach of their owner and searched in detail. Once more it is worth recalling that not everything that looks harmless really is. A careful inquiry now could save time, embarrassment, or blood, later.

Practice Makes Perfect

It is not possible for you to learn everything there is to know about searching by watching a video or reading a magazine article. To be effective, your searching routine must be practiced and critiqued under the tutelage of a skilled, patient instructor.

Effective searching techniques, like many skills called upon in the law enforcement field, are at least to some extent motor skills. And motor skills tend to fade with the passage of time unless they are practiced. Hands-on training and periodic practice in the right way to do a search is a must for any officer intent on staying safe on the street.

Handling prisoners is one of the more dangerous things that you do on a regular basis. Skipping a search or doing a poor search can result in tragedy. But by searching carefully and systematically the immediate surroundings, clothing, and persons of those you arrest or detain, you can dramatically reduce the likelihood of you or a fellow officer being killed or seriously injured while on duty. All it takes is the application of sound judgment, attention to detail, and the technical skill required to look carefully for trouble. In a profession where oftentimes routine can be dangerous, getting into a very systematic and thorough routine when it comes to searching can mean all the difference in the world.

Strip Searches

You must be careful to follow your jurisdiction's laws and your agency's regulations before having a prisoner remove all of his or her clothing for a search for weapons or contraband.

Before any search can commence, you must be able to clearly delineate why you feel the subject may be concealing weapons or contraband under his or her clothing or within his or her body. You have to have more than a "hunch" that this is the case.

The search must be conducted in a private place out of view of others or camera surveillance. And it should be carried out by two officers of the same gender as the subject being searched. If an object is seen or suspected within a body cavity (with the exception of the subject's mouth), it is to be recovered only by a medical professional or the subject.

Finally, be sure to document your reasons for the search and keep records of what you find.

Prisoner Handling Checklist

Follow all of the basic officer survival guidelines that you observe for any kind of contact with a potentially dangerous individual.

Never be lured into a false sense of security by an apparently docile, cooperative prisoner.

Follow careful weapon retention practice any time you are in the presence of a prisoner-yours or another officer's.

Keep your subject at a physical disadvantage throughout the handling process.

Follow correct handcuffing practices with your subject.

Always keep looking for the next threat, whether it comes in the form of an undiscovered weapon or an associate of your subject showing up to interfere.

Do not allow family, friends, or associates of your prisoner to come into physical contact with him once he is in custody.

Never forget that experienced criminals can be very innovative in finding ways to hide weapons.

Remove from your prisoner's custody anything with which he might hurt himself or someone else.

Always search the prisoner area of your police vehicle both before and after a transport.

Learn from your every experience with a prisoner to get better and safer for the next one. Never stop learning.

Gerald W. Garner is a long-time member of the POLICE Advisory Board and a division chief with the Lakewood (Colo.) Police Department. The 33-year veteran holds a master's degree in administration of justice and writes often on officer safety topics. His six books include two on officer survival.