Two recent events—the Boston Marathon bomber manhunt and the Cleveland kidnappings—illustrate the complicated relationship between the Bill of Rights and effective crime fighting. Essentially, because of the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution, you are damned if you do and damned if you don't. And the public has no sympathy whatsoever for your precarious position.

There was a time in Colonial America when the authorities could break into anyone's home in search of criminals or, more likely, revenue. The king's tax collectors accompanied by the king's soldiers would barge into people's dwellings and businesses without warrants and take inventory of their belongings and merchandise to ensure that the appropriate excise tax was paid on said goods.

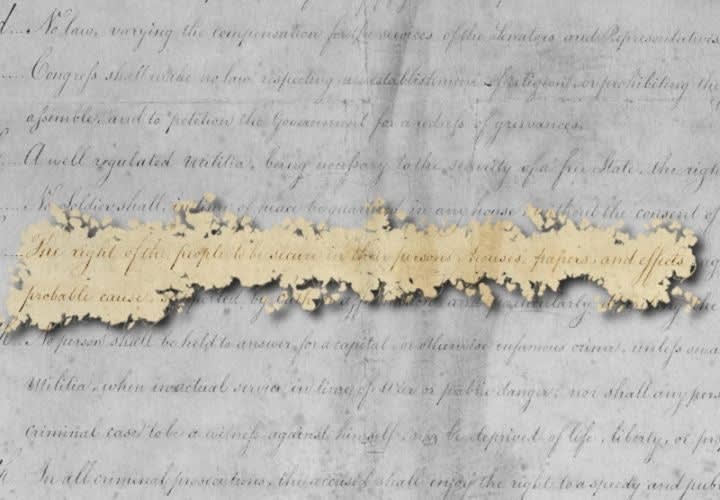

A sense of outrage regarding the king's authorities and their warrantless searches carried over after the American Revolution and was the impetus for the Fourth Amendment to the Constitution. The Fourth Amendment prohibition against warrantless search and seizure is one of the fundamental rights of all Americans. It's also the grounds for many "civil rights violation" lawsuits filed against law enforcement officers, agencies, and the government entities that employ officers. The Fourth Amendment comes into play in bad searches and bad arrests.

Quite frankly, the Fourth Amendment can be a hindrance to crime fighting. It's the reason that a bad search can lead to evidence against a suspect being thrown out of court. It's why you can't just search a guy's car at a traffic stop when every fiber of your body tells you that he is up to no good. It's also why the police in the Boston area and the city of Cleveland are being criticized for the ways they handled the manhunt for the Marathon bombers and the investigation into the abductions of three young women.

Former congressman and Libertarian hero Ron Paul has slammed the methods that law enforcement agencies used in the manhunt for the second Boston Marathon Bombing suspect. Paul argued that law enforcement ordered a lockdown of Boston and its suburbs and systematically violated the Fourth Amendment with searches of homes and businesses. But his argument does not stand the accuracy test. The lockdown was actually voluntary and the searches were conducted with the appropriate constitutional permissions. Still, Paul and his ilk believe that what happened in Boston after the bombing smacked of a police state.

The Cleveland kidnappings present an even more complicated portrait of how the Fourth Amendment hinders crime fighting and opens you up to criticism, regardless of your actions. As almost everyone knows from media coverage, three young women were reportedly kidnapped and held as sex slaves for more than 10 years. Neighbors of the suspect blame police for failing to follow up on complaints about the house. They say they informed police that they heard banging inside the supposedly empty home, that they saw its single known resident bringing in lots of fast food, that the house's windows were covered with black plastic, and that they saw naked women on leashes in the backyard.

There is no evidence that the Cleveland Division of Police received these complaints or that the house or its owner were on the radar of detectives investigating the kidnappings. But let's suppose that the house was an investigative target and the complaints were investigated. It's doubtful that it would have made any difference. Only one of these complaints, the one about naked women in the backyard, likely would have resulted in a warrant from a lenient judge. The others taken singularly and with no other evidence would probably have not met the hurdle of probable cause.

Critics in Cleveland believe the police should have done something. Critics of the Boston PD and other agencies involved in the bomber manhunt believe they did too much.

And it all comes down to the Fourth Amendment, one that you swore an oath to defend, regardless of how difficult it makes your job. As Americans we wouldn't have it any other way, except when our loved ones are the victims of criminals. Then we'll scream at you and ask you why you didn't do something.