First, let me say that the experiences or tactics described in this article will not apply to every situation law enforcement encounters. There are simply too many variables for a given technique to ensure officer safety or the safety of anyone directly or indirectly involved in a given scenario. These are my personal experiences as a law enforcement officer.

Embracing Empathy

Within any officer’s response repertoire should rest a sincere level of empathy for the person in the encounter, be that person a victim or offender. Mental health awareness training will help any officer recognize the signs of a given mental illness or neural disorder. However, such training does not a mental health professional make.

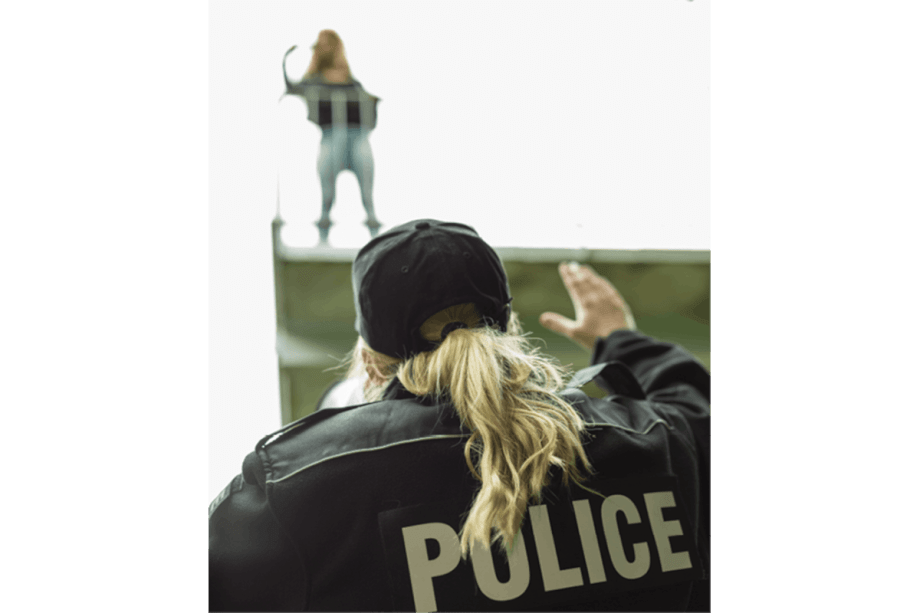

So, what standard exists that will empower every officer with the proper approach to a confrontation arising from an allegedly emotionally disturbed offender? Empathy remains a primary tool. While I served in law enforcement, I encountered multiple instances where I faced an alleged offender or victim with a possible mental health issue.

If dispatch advised that the offender may be mentally ill, my first step was to request that the offender’s counselor meet me near the scene for a brief conference before I proceeded with the call. Quite often, the counselor could share methods he or she knew might defuse the situation. However, counselors are not always available at a moment’s notice, which leaves the officer to face the situation alone.

Staying Calm

This leaves the officer with the need to develop a heightened sense of situational awareness that incorporates one’s ability to recognize inherent red flags (warnings of impending dangers) and awareness of non-verbal clues (body language) that will help bring calm to the situation. This requires that the officer remain calm in the situation as well to ensure that he or she does not allow personal emotions to overwhelm their control.

During my career in law enforcement, such encounters were numerous. My approach to each remained unique to the immediate challenge. One event included a teenage boy who destroyed his home’s interior and exterior with a baseball bat. Instead of making it to the scene immediately, I asked dispatch to invite a mental health counselor to meet me at the scene. The counselor explained to me that the boy loved the sheriff motif of the Old West and that since my deputy sheriff’s uniform resembled the uniform of a cowboy lawman that I may be able to use that alone to resolve the situation. The approach achieved the desired results. I walked toward the bat-wielding teenager while whistling a popular western song. When I was near the offender, he stopped beating the bat against the house. I shared that I was looking for criminals in his area and asked if he had seen any. During the conversation, I motioned for the counselor to join us, defusing the situation.

In another situation, I encountered a resident who was, at times, a threat. Approaching with caution and control in the least threatening manner offered the true solution. Late one evening, I was dispatched to a desperate call from the owner of a local all-night diner. A man had shoved all the tables to the outside walls while patrons huddled in a corner together. He had stripped to only his jeans and bare feet as he danced to a song on the jukebox.

I entered and watched as he moved around. He stopped dancing and stood staring at me. I returned his smile and made no move against him. Finally, he asked, “What’s up, Goodson?” I told him that I liked his choice in songs but encouraged him to gather his clothes and follow me outside so that the customers could return to their meals. His aggression returned as he gathered his boots and shirt and followed me outside.

As we approached the patrol car, he dropped his clothing to the ground. He squared off, ready for a fight. I asked, “What are you doing?” He announced, “I am getting ready for our fight. We are going to fight, right?” I told him that it was too cold to fight and that all I wanted to do was to take him to the warmth of his home, which was only a few miles away. He agreed that he was freezing, entered the rear of the patrol car, demanding that I take him home. I obliged and released him to his parents.

These scenarios only touch the surface of the encounters I have experienced during my career in law enforcement. Does this column offer ready solutions to any given encounter? Not hardly.

Instead, my intent is to focus on immediately assessing each encounter check our own emotions with the understanding that our body language or non-verbal clues may set the tone for the situation. If we can master our own emotions, we are afforded the opportunity to bring resolution where, otherwise, none would exist.

Barry Goodson is a former Marine and law enforcement officer who teaches criminal justice at Columbia Southern University. He is the vice president of the Human Trafficking Investigations & Training Institute and an administrative trainer for the Department of Homeland Security Bomb-Making Materials Awareness Program. Goodson is the author of “Country Cop: True Tales from a Texas Deputy Sheriff.”