Photo: Bryan McKean

Photo: Bryan McKean

Not since 9/11 has any one criminal incident shaken the American people like the Newtown, Conn., massacre of elementary school students and their teachers at Sandy Hook School. Consequently, the threat of active shooters is on the minds of both the public and law enforcement. And perhaps now that so many people in law enforcement and the public are looking for ways to prevent active shooter attacks, it's time to rethink the way that we respond to these attacks.

When I first became a police officer, I viewed responding to an active shooter event, especially at a school, as the most stressful and significant thing that I would ever possibly experience. I spent hours researching the subject as a whole by researching previous events, both in the U.S. and abroad.

After I became an instructor for my department, I expanded my research by polling officers and agencies from across the country. I have also had the privilege of attending some great training offered by some very reputable trainers and training groups.

Based on my research and training, I am of the opinion that the standard "quad," four-officer response is not only ineffective, but impractical. In fact, the only incident I know of where an attacker was stopped by a four-officer or more team response was the 2003 incident at Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio.

In all of the incidents I have researched, once the shooters were confronted by an armed response, no other innocents were killed. In each of these incidents, with the exception once again of the Case Western Reserve University shooting, the initial armed response met by the attacker consisted of one or two officers or civilians.

That's why my agency started with a two-officer response when it created its active shooter response program. In addition, the training encourages any officer who is willing to go in solo to do so. The single-officer response that ended the 2009 Carthage, N.C., nursing home shooting and the reaction by a single, off-duty officer that helped stop the 2007 Salt Lake City Trolley Square Mall shooting are excellent examples of how one officer can make a very big difference.

The Sacrifice Question

Since my agency has started this training, there have been three questions commonly posed by participating officers.

One of the most pressing questions that we in the law enforcement community must answer about active shooter response involves the sacrifice of officers to save endangered civilians. In other words, in an active shooter incident, are losses of police officers acceptable?

The short and long answer to this question is an emphatic no. But if that's true, how can we encourage single-officer response to such a dangerous situation?

Despite what you might think, single-officer response is not the same as sacrificing an officer to save innocents. A single officer on scene has advantages when engaging an active shooter that tip the odds in that officer's favor.

Officer vs. Shooter

You have been trained to deal with active shooter incidents. In most cases, the active shooter is not a trained combat operative. You have been trained and you can use your training to take the fight to him and foil his plans for mass murder.

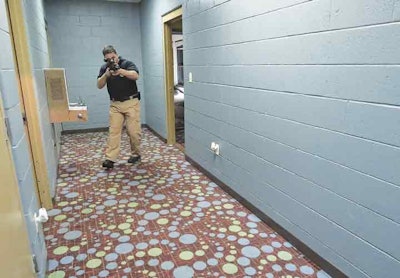

If you have received the proper training for responding to an active shooter, then you should know how to search a building for a shooter without unnecessarily exposing yourself to fire. Tactics such as corner rounding, sometimes referred to as slicing the pie, bounding, and use of cover and concealment are practical skills that we all should have and should be refining on a regular basis.

One great way to practice these techniques and tactics is in force-on-force training. Many agencies, especially those that are progressive, make force-on-force training with airsoft guns, Simunitions, or paintball guns an integral part of their regular training schedules. The benefits of this type of training are well known, and if your department doesn't provide it, then find some of this training on your own. It's the kind of experience that can really make a difference when the bullets are real.

Another advantage that you have over most active shooters is the quality of your weapons. Long guns, especially patrol rifles or carbines, have become much more prevalent in today's police arsenal. A long gun is a force multiplier that allows a trained single officer to put accurate fire into targets at greater distances than those afforded by handguns. Remember, distance favors the trained shooter.

Even your duty pistol has many inherent advantages over the usual handguns preferred by active shooters. Double-stack magazines allow you to carry enough ammunition to stay in the fight long enough to prevail. As a professional, you have probably also taken the time and effort to customize your pistol to meet your needs. Accessories like adjustable grips, night sights, laser sights, and tactical lights increase your confidence and will help you put accurate fire on a target under stress.

You are also probably better with your chosen weapon platform than the average active shooter. This not only includes accuracy with multiple shots under stress, but also reloads, transitions, and malfunction drills.

Another advantage that you can bring to a fight with an active shooter is the ability to make hits at greater distances than generally practiced on shooting ranges. Look at some of the hallways, gymnasiums, cafeterias, and parking garages in your patrol area. What is the range from one end to the other? To end an active shooter incident, you may have to make a shot with a pistol at more than 75 feet or with a rifle at more than 150 feet. So practice shooting at these distances.

Your body armor may also make the difference in a confrontation with an active shooter. And hopefully the bad guy won't have armor, although in recent incidents, active shooters have worn both ballistic vests and helmets. If you encounter an armored shooter, you will have to change your approach to targeting. Shoot where he doesn't have protection. One really strong target is the hip. Hardly anyone thinks to protect it; it's a substantial target, almost as big as center mass; and hip and pelvic wounds are extremely painful and capable of incapacitating a threat.

Finally, the biggest advantage you have over the bad guy is that you can call for backup and other cops are on the way to help you. No one is coming to help him. Yes, there could be more than one shooter, but the cavalry is coming to help you. Backup will be arriving on scene, and it will consist of trained, highly motivated officers who are ready, willing, and able to help you. You may have gone after the shooter alone, but you won't be alone for long.

The Cost of Waiting

One question that all officers have to answer for themselves is how long will they wait for backup before engaging an active shooter.

I believe the answer to this question is: However long it takes me to get my rifle and my go-bag out of my trunk.

During an active shooter incident, you are dealing with a very brutal equation: Time taken by first responders equals casualties. One of the largest body counts from an active shooting incident so far is the Virginia Tech University incident of 2007. Depending on which after-action report you read, the attacker shot an average of eight people and killed two every minute. We have to get in quickly and end the killing.

Friendly Fire

One of the most important questions I have been asked by a student during active shooter training is about the potential for blue-on-blue casualties. If first responders are going into the same building at different intervals, and even different entry points, don't we have to be worried about "friendly fire?"

Yes, friendly fire or crossfire situations are always a concern. This should be addressed in training, through both force-on-force and tactics training.

As officers, it is a given that we are responsible for every bullet that comes out of our guns. That means that we must be sure of our target, but also what's beyond it. You can't just open up on the first person who has a gun; you have to make sure that he or she is not a cop before pulling the trigger.

Knowing your target is just one aspect of having the right mindset to end an active shooter attack. You have to think like a hunter and drive toward the threat.

You also have to keep in mind that the active shooter is a hunter, too, and he is driving toward his prey. Active shooters are relentless in the pursuit of victims, and they usually don't stop until taken down by bystanders or confronted by police, which usually results in them surrendering or committing suicide.

When you think about responding to an active shooter incident, consider what you would want responding officers to do if such an incident were to happen where your children go to school or where your spouse works. Would you want that officer to wait for backup or go in after the threat?

And ask yourself what are you willing to do on your own, outside of the training provided by your agency, to ready yourself to prevail during such an incident? It's rare that any of us receives the amount of training from our agency that we want or need. Budget considerations and departmental priorities limit training, so it's up to each of us to train on our own time and on our own dime.

J.D. Lightfoot has served as a police officer in the Midwest for more than 10 years. He has worked as an active shooter/deadly force instructor for his department since 2008.