Violent, pre-fight media melees, profane press conferences, and the illegal out-of-the-ring antics of superstars seem to be the only way to get the sports fan's attention these days.

When boxing first became popular in America, 19th-century gamblers, bamboozlers, and side-show swindlers flocked to the sport, sensing that they were on to something profitable. Fights became festivals and a cause for celebration that was challenged only by public hangings. And for the next century or so, prize fights remained the greatest spectacle in American and international sports.

But today, with ultra-violent video games, WWF, Extreme Fighting, and the horrors of the nightly news, boxing is not as spectacular as it once was and it needs its own side shows to pique fan interest. Violent, pre-fight media melees, profane press conferences, and the illegal out-of-the-ring antics of superstars seem to be the only way to get the sports fan's attention these days.

So when your city hosts a prize fight, it attracts a spectator demographic that can be a cop's worst nightmare. Blood-thirsty sports fans, who aren't satisfied until they take to the streets, bars, and hotels with their unruly and dangerous behavior; professional and freelance prostitutes targeting tourists; and the local one-percenters hell bent on teaching the Tinseltown crowd a thing or two about bar-room brawling are all part of the tapestry of contemporary boxing.

In June this circus rolled into western Tennessee, eschewing Vegas because challenger Mike Tyson was no longer eligible for a Nevada boxing license. But a huge question mark hung over the event: Could Tennessee law enforcement handle the Tyson freak show that was heading for the Memphis Pyramid?

The men and women of the Memphis Police Department had experience with crowd control, but they hadn't seen the volume of potential mayhem that comes with Las Vegas-style boxing. But they made adjustments to their crime-fighting style, and after being awarded the Lewis-Tyson fight by default, they prevailed-in spite of the fact that it was a last-minute endeavor. And the schedule gave them very little time to make preparations.

Measure for Measure

"They put me and Inspector Larry Godwin together to start working on this thing in early May, and we pulled it off," says Officer Robert Skelton of the Memphis PD. "It went absolutely wonderfully. We're in the process of putting the after-event report together, and the only problem we encountered stemmed from the crowd being so large on Front Street (outside the Pyramid), that we needed a better plan for the contraband checks. We had eight metal detectors across the front of the building, and we actually needed about 12."

Balancing the need for heightened post-9/11 security with a need to seat the crowd by 10:15 was one of the biggest problems faced by the Memphis PD. The fight was broadcast on cable TV in the United States and on a number of satellite feeds worldwide, so there was no way to delay its start. With ticketholders stacking up at the doors and the clock ticking, the security check was accelerated and the fans were in their seats in time for the opening bell.

In addition to the metal detectors at the gates, the police employed other high-tech security tools at the Pyramid. And they were able to piggyback their surveilance efforts onto the equipment supplied by the cable TV team.

An FBI agent was stationed in an HBO production truck, "so we had cameras that we could use to zoom in on something anywhere in the building," says Skelton.

Tales of the Tape

While ''Officer Friendly'' and ''Johnny PIO'' led the media to believe everything was well in hand, the boys in black behind the scenes were gropin' and scopin' high and low. And that wasn't just during fight night. The pre-fight hoopla was also a cause for concern.

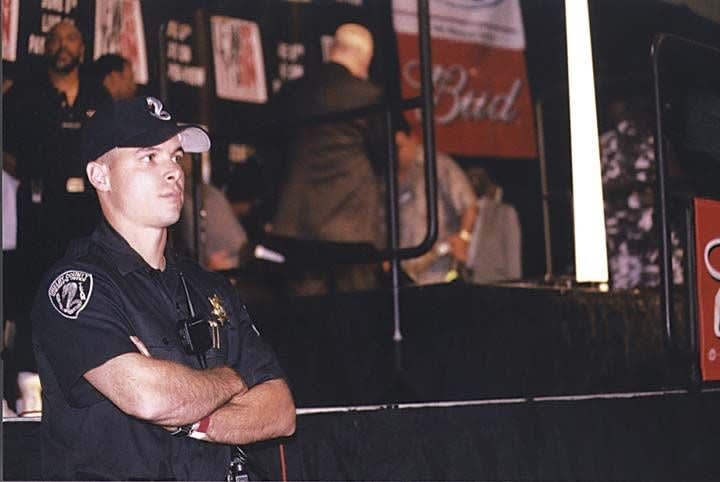

Given the pre-fight melees that have taken place during past Tyson press conferences, the Shelby County Sheriff's Department SWAT team took no chances with ''Iron Mike's'' weigh-in at the convention center. Officers were in full battle fatigues, and didn't hesitate to get in the faces of hundreds of feisty photographers and reporters from all over the world, who were pushing boundaries and challenging limits.

It's no secret that a lot of boxing fans like to fight as well as watch fights, and the Tyson weigh-in-like most of his publicity events-brings out this fury.

It doesn't help that the Tyson crew does nothing but add gas to the fire. One of the Tyson troublemakers is Stephen "Crocodile" Fitch. Crocodile, who has become a staple at these staged fiascoes, looks like a weird combination of Meadowlark-Lemon and Mr. T, but muscle bound, and a lot meaner. He generally mills around the media area juking and jiving with journalists before the events, and then just before Iron Mike arrives, he turns up the volume and the vitriol; at times directing it at specific members of the press.

"He [Crocodile] is one of Mike's boys... he comes to all these things," said a SWAT team member, as three or four of his colleagues moved toward "the croc."

While the SWAT officers refused to divulge the intelligence they had on Crocodile, anyone who saw the Tyson press-conference-turned-near-riot in New York last winter, may recall a husky fellow dressed in camouflage fatigues who landed his share of punches on members of the opposing camp. That's Crocodile, and in Memphis, the police kept a very close eye on him.[PAGEBREAK]

Ring Riots

Mike Tyson's ring antics attract no less disturbing behavior than his pre-fight bluster. When he bit off a piece of Evander Holyfield's ear in Las Vegas in 1994, the referee stopped the fight, triggering a riot in the arena.

Tyson's history of being a magnet for violence was one of the reasons why planners concentrated a good portion of the security response inside the Pyramid arena on the ring itself.

Preparing for any rumble in the stands, the Memphis PD actually organized a small cache of riot gear under the ring. "We had 12 riot shields and some other things there, and the main reason was because we had the mayor and the governor on the floor, so in the event of a bad situation, we wanted to be able to protect them and the fighters," says Skelton.

As for officer presence, the department put together two ring-walk teams, which consisted of seven officers each, as well as three six-officer teams, and one eight-officer team charged with responding in the event the ring was rushed.

"One of the six-officer teams was responsible for getting the mayor and the governor out of the building, if something happened," Skelton explains.

Another issue police had to deal with was the negotiation with the camps. Skelton explains that the boxers and their entourages tend to ask for a lot of things that adversely impact security, such as having too many members of a fighter's entourage at ring side. "You just have to say 'no,'" he says. "But we handled it diplomatically, and I think everyone left with a real good feeling."

Although by all accounts the Memphis security was effective and the event went off with few visible hitches, not everyone was thrilled with the idea of pulling so many Memphis cops off counter-terrorism duty to babysit a couple of overpaid brawlers and the celebrities who could afford ringside seats.

For the cops involved, the general attitude toward the babysitting duties was boredom. But they performed their duties with professionalism and efficiency.

Kathy Benton, K-9 agent with the ATF, is a prime example. Benton was charged with sweeping the Sam's Town Hotel arena, where Lennox Lewis held a press conference and brief training session for hundreds of journalists. Although she was cordial, it seemed like "the luncheon" detail was a yawn for Benton and her K-9 partner "Yahtzee," who had the unenviable task of sniffing out explosives in a space where the aromas of prime rib and roast duck ruled the room.

But bored or not, Benton and her dog took the job very seriously, as did the other agents on the detail.

Safety and caution were the watchwords of the entire operation. Before Yahtzee could even do her job, ATF agents did a walk-through to make sure the room was safe. "We have to look for glass, sharp objects...anything that might be harmful to her," says Benton.

At the end of the event Benton reported no hits from Yahtzee's sensitive and trained nose.

Ladies of the Evening

Prizefights attract a lot of men with money. Consequently, the greatest challenge, even in post-9/11 America, for the law enforcement officers who police the host cities is prostitution and the associated crime that it brings.

To make matters worse in Memphis, the region is economically depressed and some local ladies believed that servicing the fight fans was a way to make some easy money.

Prostitutes were everywhere before and after the fight. And not just the local talent. Women came in from Chicago, San Diego, New York, Los Angeles, and of course, Vegas. Add to this the local girls who headed to Beale Street after their full-time jobs at burger joints and strip clubs to spend the rest of the night working the once-in-a-lifetime international crowd and you had a major headache for the Memphis PD.

Spread Thin

As most other police agencies have discovered when their cities play host to a major sporting event, the Memphis PD quickly learned that there are not always enough officers to go around.

To counter this problem, Memphis PD director Walter Crews had a lot of "Gang Unit" T-shirts printed up, and passed them out to every auxiliary officer he could muster.

After it was all said and done, a Memphis PD PIO said everything went better than planned.

Tom R. Arterburn is an independent journalist based in St. Louis, Mo.