Non-cops might generously color such cognitive powers as acts of "intuition;" others less taken with the idea of extra sensory perception are more apt to dismiss them as some form of "profiling." By any name, Investigator Christopher Scallon had it working for him the night of April 15, 2007.

A cop's mind is a tricky thing. In a split-second it can recognize those situations wherein things have somehow deviated from the norm. Accustomed to rapidly digesting and analyzing information, it is not shy about divining reasons for disruptions of the routine.

Non-cops might generously color such cognitive powers as acts of "intuition;" others less taken with the idea of extra sensory perception are more apt to dismiss them as some form of "profiling."

By any name, Investigator Christopher Scallon had it working for him the night of April 15, 2007.

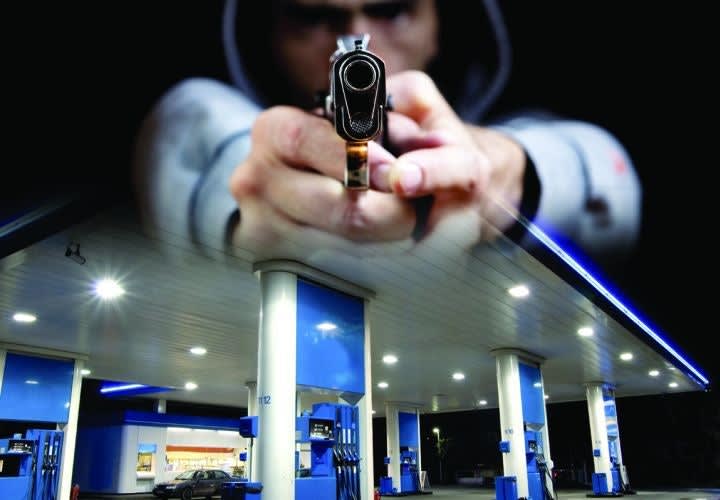

The off-duty Norfolk, Va., police officer had pulled into a Shell gas station in a bid to fuel up his car before driving to meet his girlfriend in nearby Newport News. Scallon had intended to park near the front doors so as to get in and out as quickly as possible, but found a group of people congregated near the doors. Normally, the 10 o'clock hour found the doors of the Shell Station at Granby Street and Taussig Boulevard locked and employees conducting transactions from beyond the pane of a bullet-resistant window.

Maybe they're just having a smoke break or something, Scallon thought as he parked the car nearby.

Still, something wasn't kosher. There wasn't anything that he could readily put his finger on, but it was undeniably there. Something wasn't quite right.

Having experienced such sensations before only to find some latent suspicion confirmed, Scallon found himself evaluating the postures and attire of those gathered: The man standing with his back to him in the hooded sweatshirt (not a particularly warm night)…no hands up in the air…no looks of palpable fear…

All the same…

In Progress

Draping his jacket over his gun, Scallon stepped from his ride. As he approached the front doors, he heard one of the men outside the store yell what sounded like a nickname.

In response, the guy in the hoodie spun around and spotted Scallon. The investigator could now see that the man, Paris Wynn, was also wearing a bandana and carrying something in his hand. Clad entirely in black, Wynn's eyes were the only part of him visible through the bandana and they grew large upon seeing Scallon. Wynn suddenly pushed the clerks from outside to inside the store.

Realizing he'd probably happened upon a robbery in progress, Scallon gave chase. Years of working narcotics had conditioned Scallon to the inherent threats associated with plainclothes attire. Muscle memory kicked in and his chain-tethered badge came out of his left front pocket. Tossing it around his neck, Scallon yelled, "Police officer!" as he crossed the store's threshold.

That was enough for Wynn. He pointed his gun in Scallon's direction and fired.

The door jam next to Scallon pinged with the impact of Wynn's bullet. Leveling his own Glock 9mm Model 17 on the gunman, Scallon aimed for center mass. He squeezed the Glock's trigger. The round center-punched Wynn and caused the robber to stagger backward.

Wynn retreated down an aisle. Scallon pushed a bystander behind the cashier's counter. Then he tried to track Wynn as the man darted back and forth down the aisle a row over.

The store's shelving units were only about four-and-a-half-feet tall and barely constituted concealment, let alone cover. Save for the obscuring potato chips and other foods occupying the shelves, the two men could see portions of one another through the slats. Still, that was more protection than what the front of the store afforded Scallon.

Worse, Scallon knew that there was another possible threat outside of the store. Someone outside had yelled to warn Wynn. Scallon didn't know where that person was or what his intent might be, but he did know that he could be targeted through the store's plate glass windows, which offered him no concealment. But rather than be distracted by the possible whereabouts of the man who'd shouted to Wynn, the investigator resolved himself to committing his attentions to Wynn.

Moving down the aisle, Scallon fought for his balance, sliding on the blood-slicked floor. The balancing act didn't stop there, for the investigator was simultaneously determined to keep Wynn from not only getting to the front doors but also to two employees behind the counter. There was no way that Scallon was going to allow the man to take them hostage or somehow allow them to get caught up in the crossfire.

The dangerous game of cat and mouse continued, with Wynn darting back and forth between the aisles, angling for a means of somehow putting the officer down or getting by him through the store's only exit, the front door. Periodically, the suspect would pop up over the top of an aisle to squeeze off a round at Scallon who'd return fire with greater accuracy. At least, that's what he thought.

And yet the SOB wouldn't go down.

Buttonhook

That the suspect might be wearing body armor crossed Scallon's mind. But Scallon also knew that if the man had been in a vest he probably wouldn't be sliding around in his blood.

With each passing minute, Wynn's determination became more desperate, his willingness to take the fight to the investigator more brazen. A mere aisle now separated the two men, and Scallon knew that he'd have to do something to end this. He'd committed himself to closing the gap just as Wynn moved to his right.[PAGEBREAK]This is my chance. Get hurt trying, or get hurt doing nothing.

Scallon planned to buttonhook the man around the aisle end. But as he made his move, so did Wynn, who reached blindly around the shelf and fired at him.

So much for that plan, Scallon thought.

Collapse

Scallon backed off from the corner and Wynn went on the offense, rounding the corner on him. It would prove a fateful

decision.

From aisle to aisle; from moment to moment; from shot to shot, Scallon had felt a steady surge of adrenaline course through him. But at that instant when it most counted, seeing Wynn's head come into view, he found his grip surprisingly firm and steady. Devoid of any shakiness and with slow deliberateness, Scallon lined up his sights on the gunman's face and squeezed the trigger of the Glock.

The round struck Wynn directly below his nose and his head jerked back

violently.

Scallon had fully expected the man to collapse in a heap. Instead, Wynn began to run wildly around the store.

Figuring that Wynn might still try to charge him again, Scallon now opted for the protection of the cashier counter. No sooner had he than Wynn staggered up the middle aisle. Some 10 minutes after the first round had been fired, Wynn stumbled directly in front of the counter where he collapsed, pulling down a potato chip rack on top of himself.

Making the Approach

Scallon came up over the counter and repeatedly challenged the downed suspect.

"Raise your hand!"

With each command, Wynn silently raised his hand up only to drop it back down. Scallon figured that Wynn was genuinely having difficulty holding his hand up given the number of bullet wounds he could now see on the man's body, but he wasn't going to take any chances. Continuing to demand that Wynn keep his hand raised, Scallon accepted a store phone from an employee with his free hand.

Scallon advised a police dispatcher that he was an off-duty officer and had just been involved in a shooting then described his attire and location before handing the phone back to the employee.

Minutes later, a fellow Norfolk officer arrived on scene.

Even with the benefit of better visibility, Scallon wouldn't have expected the uniformed cop to have recognized the bearded man in a Brooklyn Cyclone jersey and knew that the blood soaked floor and heavy gun smoke in the air would only give the officer more pause to enter. Holding up his badge, Scallon yelled through the window that he was the u/c police officer and for the officer to join him.

Once inside, the two officers made a cautious approach of the downed suspect, with Scallon providing cover. He told the officer to get some gloves on before cuffing the injured Wynn whose torso moved with the uncertain jerkiness of a newborn, his state of lucidity still in question.

As Wynn was handcuffed, other units arrived en masse. Scallon walked over to the site of the last exchange of gunfire. Spotting Wynn's discarded sidearm lying there, he felt some momentary peace of mind: He knew beyond any certainty of a doubt that Wynn had been armed when he shot him.

Upon surrendering his own firearm to arriving officers, Scallon found that there was only one round left in the chamber; he'd expended some 17 rounds during the firefight.

Despite emptying his own revolver, Wynn had fortunately missed his target each time. Fighting paramedics all the way, Wynn was transported to the hospital where he later died.

Eleven of Scallon's shots had struck Wynn, 10 in vital organs. The first shot had also proved to be the fatal one, but Wynn just didn't realize it. The balance of his rounds were likewise significant, with his last shot entering Wynn's nose and exiting at the back side of his ear.[PAGEBREAK]Coping With It

With his partner in crime, the 23-year-old Wynn had been responsible for a series of robberies throughout the Norfolk region. The two men had taken turns as look-out and robber. Less than an hour earlier, the partner had himself been the gunman on a robbery at another Shell station on Tidewater Drive; he was to have been Wynn's getaway driver had Wynn succeeded in getting past Scallon. Detectives would clear some 30 robberies between the two men.

Looking back, Scallon recognizes where both his undercover work and a willingness to take off-duty action worked in his favor.

"I always had my badge on me, and if I ever had to pull my gun out, I automatically yelled, 'Police officer!'" the investigator reflects. "If only for the fact that not everyone knows that I'm a police officer, I want to make it completely clear that it's not two bad guys shooting it out with each other."

The incident left a dramatic impact on Scallon nonetheless. "I wasn't hungry for seven days after the shooting, as I went through the whole gamut of emotional problems," he says. "I lost 50 pounds [and I] became hypersensitive. People couldn't understand that flippant comments like, 'Good job, killer,' would bother me. I'd spent my entire life trying not to harm people, but the nature of the job is that eventually you may have to. They couldn't understand why I would feel bad for killing someone who was trying to kill me. That was a conflict that I had with myself and with other people who were trying to be supportive. They'd say, 'You did a great job.' I don't think that I did a great job; I did the job that was required. I think it was just, but there was a lot of inner turmoil."

Required by the department to see a doctor, Scallon met with a psychiatrist who said he understood what he was going through. The investigator immediately resented the overstated empathy.

"I hadn't talked to anyone about the shooting, so how could he understand?" Scallon asks rhetorically. "The man had never been involved in a shooting, but said that he'd been around a lot of people who have."

Scallon told the shrink off. "You have no clue what you're talking about and I don't want to talk to you," Scallon told him.

Later when a female psychiatrist-who'd likewise said that she knew what Scallon was going through-also admitted that she had never been involved in a shooting, Scallon's response to her was unprintable.

Scallon left the office angrier than when he'd gone in. He resented being obliged to talk with someone who hadn't been in his shoes, and questioned the credibility of anything that the two might have to offer.

Eventually, Scallon did receive help from someone who could give it: A fellow officer who had engaged a suspect who'd also killed the officer's partner.

"We met at a location away from the police department, in plain clothes," Scallon recalls. "We talked for three hours and not a bit of it had anything to do with the police department. It was just a nice chat and it felt good. He told me to call if I ever wanted to talk again."

The officer gave Scallon a piece of advice before leaving. "You need to see a doctor or you're going to explode."

Scallon respected the officer's opinion and, armed with new insight, acted on the advice. It paid off.

These days, Scallon knows that the unique dynamics of his particular shooting had a lot to do with his emotional response to it, including his hair-trigger temper and his touchiness.

"If the shooting had been over after a couple of seconds, I would have had symptoms, but not as bad. The prolonged shooting-anything over 10 seconds-causes you to go into survival mode. After the shooting, I took off my jacket and was numb. I didn't know if I was hurt, only that I felt emotionally drained. Coming to terms with all this helped clear my head."

Scallon says he is appreciative of the assistance that he has received since the shooting and the department's willingness to have him discuss the matter candidly. And in retrospect, he knows that some of his acting like a jerk was even cathartic as it allowed him a release until he was willing to recognize more appropriate channels for dealing with the shooting.

A letter to police Chief Bruce P. Marquis from the Commonwealth's Attorney Jack Doyle summed up Scallon's heroic

actions:

"Only when Wynn responded by opening fire upon the investigator in the presence of two innocent civilians did Investigator Scallon resort to deadly force," Doyle wrote. "Investigator Scallon should be commended for his bravery and dedication in putting himself in harm's way confronting this armed robber."

For his courage under fire, Scallon received his department's Medal of Honor, as well as the Virginia Public Safety Medal of Valor. He has since been promoted to sergeant and continues to serve the citizens of Norfolk.

What Would You Do?

Put yourself in the shoes of Investigator Chris Scallon. You're wearing street clothes and you've come upon a robbery in progress at a business. Now ask yourself the following questions:

When contemplating a robbery being committed in your presence, are you philosophically inclined more toward taking action or merely being a good witness? What factors determine your decision to transition from one to the other?

Whether or not you currently work in an undercover capacity, do you feel that you've taken adequate precautions to make yourself identifiable to arriving law enforcement personnel in similar situations? Do your off-duty activities often put you in jurisdictions where you do not know any of the local officers and they have no idea who you are?

Investigator Scallon made a conscious decision to position himself between the suspect and the employees. Would you have done the same, or opted for the cover of the counter in the first place?

A vast majority of officer-involved shootings take place within a matter of seconds. This one transpired over the course of 10 minutes. Do you feel that you would be emotionally and physically capable of dealing with the immediacy of such an incident? How do you feel you would react in its aftermath? How important is it to you to be able to communicate your experiences to others?