Ernesto Miranda's story began over a dozen years before his untimely death in the downtown skid row section of Phoenix, AZ, only a few blocks from where his story ended. It is presented here by the police officer who made the investigation and arrest, and took the confession later ruled inadmissible as evidence by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Since the Court's 1966 decision requiring the Miranda Warning, much has been written on the case's judicial points; however, even police officers and attorneys who work with the results of the decision know few of the details of the actual crime and investigation.

Ernesto Miranda's story began over a dozen years before his untimely death in the downtown skid row section of Phoenix, AZ, only a few blocks from where his story ended. It is presented here by the police officer who made the investigation and arrest, and took the confession later ruled inadmissible as evidence by the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Crime

The crime involved a shy, 18-year-old woman who had just finished her shift at the Paramount Theater in Downtown Phoenix on March 2, 1963, at 11:45 pm. She boarded a bus for her home located in northeast Phoenix. She exited the bus at 7th Street and East Marlette. She had just started the five-block walk home when a car pulled up slowly from behind and stopped just in front of her.

The suspect got out of the car and grabbed her, pressing a sharp object against her throat. He ordered, "Don't scream; don't scream and you won't get hurt." He forced her into the back seat of the car and tied her wrists and ankles with rope. He drove off as she cried and begged him to let her go. He would only respond, "Be quiet. Just be quiet and I won't hurt you."

Twenty minutes later, he arrived in a deserted area northeast of the city and raped the young victim. He then stole four dollars from the victim and turned to her, stating, "Whether you tell your mother what happened or not is none of my business, but pray for me." He drove her back to town where she ran to the home of a family member to report the crime.

The Investigation

Uniformed officers responded, took the necessary reports, and contacted detectives who took the initial report. The next morning, a five-year veteran in the Crimes Against Persons Detail, 27-year-old Detective Carroll Cooley, was assigned to investigate the rape case. Cooley began with a routine interview with the victim, who provided a description of a Mexican or Italian male with dark curly hair combed back, about 25 years old, of average height and build, wearing a white T-shirt and blue jeans. She stated the car was an old four-door sedan, light green with light beige upholstery with vertical stripes, paint brushes on the floor, and the smell of turpentine in the car.

The investigation produced few results. A week passed with no substantial leads or possible suspects. Detectives noted similarity between the victim's description and those of other attacks in Downtown Phoenix.

The victim continued to work at her job, but now had a family member meet her at the bus stop to walk her home. A week after the attack, while waiting to walk the victim home, the male relative saw an old light-colored sedan with a single occupant drive slowly back and forth by the bus stop several times. He noted a license plate number of DFL-317. When the victim stepped off the bus, her relative pointed to the car parked on the dark side street to see if that could be the suspect's car. They walked toward the car and the victim thought it might be the same one, but the driver started the car and sped away. The male relative called the police, who discovered the plate was registered to a 1958 Oldsmobile; however, the relative was sure the car he had seen was a 1953 Packard.

On March 11, Detective Cooley had the MVD pull all their records on all Packards with the license number beginning with the "DFL" prefix. He found one registered in Mesa just one digit off from the number reported by the male relative. The next day Detectives Cooley and Young drove to the address of the registered owner, Twila Hoffman. The home was vacant, but neighbors stated the people who had lived there were Ernesto Miranda and his wife Twila.

They had moved out a few days earlier. The neighbors noted that they used a truck marked "United Produce" to haul their items away. The detectives checked Miranda's name with the Mesa Police Department and learned he matched the suspect's description. They also learned he had a juvenile record of assault with intent to commit rape in 1956; a juvenile arrest in Los Angeles, CA, for robbery in 1957; as well as an arrest and conviction for auto theft in Tennessee in 1959 that resulted in a one-year sentence to federal prison.

The detectives returned to Downtown Phoenix and stopped at the United Produce Company where they learned that Ernesto Miranda was employed there as a dockworker on the evening shift. United Produce did not have Miranda's home address, but they knew he had just moved. They had loaned him one of their trucks to move his family from Mesa to Phoenix. On Wednesday, March 13, the detectives continued their investigation by going to the Downtown Phoenix Post Office to see if Miranda had filed a change of address card. Their efforts paid off; they now knew where to find Miranda.

The Arrest and Interrogation

The detectives went to Miranda's new address on West Mariposa and drove up to see a light gray 1953 Packard parked in the driveway with plate DFL-312. Cooley noted the interior matched the description provided by the victim. A woman, Twila Hoffman, answered the door. She explained Miranda was asleep and went to wake him. Several minutes later Miranda came to the door and the detectives asked if he would come down to the police station so they could talk to him. Miranda agreed to go to the station, and rode in the back seat of the car unrestrained and was not under arrest.

At the main police station, Miranda was taken to the Detective Bureau and placed in the interview room with a two-way mirror for viewing line-ups. Detective Cooley began the interview. He explained to Miranda that another victim identified his license plate as being involved in the crime. Miranda denied knowing anything about the incident and claimed to be working that night at United Produce. Cooley continued talking with Miranda for over 30 minutes about his past record for assault. He stated that Miranda may need psychiatric help and was the suspect in these cases. Miranda insisted he was innocent.

Detective Cooley asked Miranda if he would consent to being viewed by the victims in a line-up with several other men of his general description. Miranda agreed after the officers told him they would take him home if none of the victims could identify him. Detective Young brought in three prisoners from the City Jail to stand in the line-up while Cooley began to locate the victims. Only two victims could be located on such short notice.

The victims arrived at the station shortly before 11:30 am. Miranda was told he could choose his position in the line by selecting one of the four large-numbered cards that would be worn around their necks for identification. He chose #1, the first position in line. The victims were unable to positively identify the suspect. One victim believed that if she could hear his voice, she might be sure. Cooley went in and told Miranda that he was identified by the victims. At that time Miranda responded, "Well, I guess I'd better tell you about it then."

Miranda confessed to both crimes and to using a nail file to conduct the assaults. The detectives asked if he would give them a written statement as to his actions. He agreed and was given a standard form. His written confession covered one kidnapping/rape/robbery of the 18-year-old victim. Since attempted rape could not be established in the other case, it would be the responsibility of the robbery detail, and they did not want to risk jeopardizing Miranda's successful prosecution by opening his written confession to attack because of the mention of other, unrelated crimes.

After completing the statement, the first victim was brought into the room and Miranda was asked to state his name and whether he recognized the woman. He stated his name and said he did recognize her. After leaving the room, the victim stated she was positive Miranda was the man who had raped her. She was sure the moment he spoke. The same occurred with the second victim. Detective Cooley told Mr. Miranda that he was under arrest for kidnap, rape, and robbery, and he was handcuffed and booked into the fourth-floor city jail.

The detectives didn't consider Miranda to be under arrest until this time. The U.S. Supreme Court disagreed, assuming the arrest to have been made at Miranda's home. Prior to his verbal admissions, they would have had difficulty justifying holding Miranda if he had demanded that they either charge or release him.

The Miranda Decision

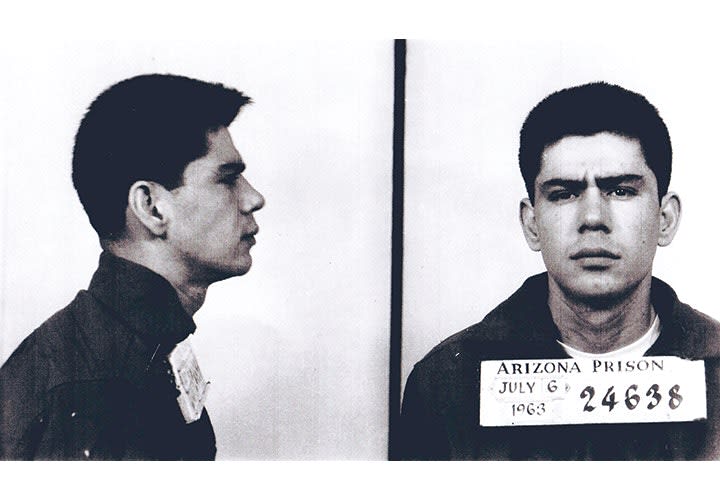

Miranda was tried in Superior Court June 18–19, 1963, based on the face-to-face identification, and part of his verbal confession was admitted as evidence. He was convicted and sentenced to 20–25 years on one incident and sent to the Arizona State Prison at Florence. Within a week, he was tried on the second incident and was sentenced to 20–30 years in Arizona State Prison. Two years later, a court-appointed lawyer appealed the case to the Arizona Supreme Court. He charged that Miranda's constitutional right to legal counsel in one case was denied. The court ruled that since Miranda hadn't asked for an attorney to assist or represent him at the time he was questioned by police, and since there was no legal requirement that he be advised of his rights to such counsel, the conviction would be upheld.

After the failed appeal, John J. Flynn agreed to try to have the case reviewed by the U.S. Supreme Court at the request of the American Civil Liberties Union. The court agreed to a review in October 1965. The U.S. Supreme Court reviewed three other cases that involved the same type of issues at the same time. The resulting decision was actually based on the Court's review of all four cases; however, since Miranda v. Arizona was the first case listed, it became generally known as The Miranda Decision. The U.S. Supreme Court returned the case to Maricopa County Superior Court for retrial. Miranda's conviction in the first original trial was not included in the appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court; therefore, the court's ruling was not applicable to that case. He still faced a 25-year prison sentence regardless of the outcome of his new trial.

The other case was tried and the judge ruled that the victim's identification of Miranda was inadmissible on grounds that she had not been completely positive when she initially viewed the line-up. However, the jury found him guilty a second time and again the conviction was based heavily on his own admission and confession.

Miranda was sent to Arizona State Prison to serve both sentences concurrently. He remained incarcerated there until he was paroled on Monday, April 28, 1975.

The End of the Line

The story did not end there. Miranda began hanging out at the old Deuce, the Downtown Phoenix area where wholesale product markets were once the hub of the area's commercial activity. He made money by selling Police Miranda Warning Cards, which he would autograph for one dollar. But his life ended on January 31, 1976, shortly after 6:00 p.m. at the Amapola Bar, 233 South Second Street. He was playing cards at the bar with two other individuals. A fight erupted and Miranda was stabbed in the chest with a long-bladed knife.

The suspect was later located and read his Miranda rights for the murder of Ernesto Miranda. The circle was complete; the suspect became the victim and his own original case influenced the interview of the suspect that killed him.

Robert Demlong retired as a commander with the Phoenix (AZ) Police Department and now serves as treasurer and co-curator of the Phoenix Police Museum.

More from The Phoenix Police Museum

The Phoenix Police Museum exists to educate the public about the history of the Phoenix (AZ) Police Department through a positive learning environment. It is free to attend, although donations are accepted. Exhibits include "Miranda, You Have The Right To Remain Silent," which looks at the story of Ernesto Miranda and the origins of the Miranda warnings; "Technology Changes Through The Years;" and the "Children's Dress-Up Station" that lets kids wear a real Phoenix Police uniform and get "sworn in" as a police officer, complete with sticker badge.

In October 1993, the Phoenix Police Museum started as a small exhibit at the Historic City Hall, 17 S. Second Ave. With the assistance of Cindy Myers from the Phoenix Museum of History, a temporary six-month display was created. The event was enthusiastically received. The Arizona Humanities Council funded a study of the artifacts which demonstrated that the museum had ample material existed to open a small museum.

Barrister Place was selected as the permanent site of the museum. Through generous donations from Motorola, the area was painted and re-carpeted. Home Depot, Store #455, donated construction material for the creation of exhibit areas. The Phoenix Police Department provided phones and an alarm system. Volunteers prepared the exhibits including a mock-up of a 1910 city street and an old jail cell. The opening of the first exhibit in the Barrister Place location was on Friday, Oct. 6, 1995. In 2012 the museum moved to its current location at Historic City Hall, which was the home of the Phoenix Police Department from 1928 until 1975.

For more information about the Phoenix Police Museum visit https://phoenixpolicemuseum.org/