Few law enforcement topics fire the imagination of the American public like the resolution of a cold case. Americans love a mystery, and no mystery is more enticing than a “whodunnit” from decades ago that remains unsolved. That’s why there are so many cold case books, TV shows, blogs, and podcasts.

10 Tips for Successful Cold Case Investigations

Building and maintaining an effective cold case unit involves assigning the right personnel, training them, and giving them the necessary resources and support.

The wall of cold case victims at the Fairfax County (Virginia) Police Department.

Fairfax County PD

Loosely defined as criminal investigations that led to no arrest and are no longer actively under investigation, cold cases used to be just cases long forgotten. The evidence was stored and no one involved was still alive, even the family members and loved ones of the victim had passed, and very few in law enforcement still cared. Except for notorious murders like the Black Dahlia or the disappearance of Jimmy Hoffa, cold case investigations that attracted public or even media attention were just not common.

But then about 30 years ago, DNA profiling became a practical investigative tool and the possibility of using the technology to solve decades-old cases became a very real thing. Today, advances in DNA profiling and other scientific forensic methods have made more cold cases solvable. And the popularity of genetic DNA analysis by people researching their genealogy has even been exploited to bring infamous criminals such as the Golden State Killer to justice.

These advances in forensic technology have made it more likely that cold case investigations will yield results and more likely that agencies that do not have cold case programs are considering starting them. But there are challenges to creating cold case units, not the least of which is the almost crippling shortage of officers at some departments. Still, a cold case investigation unit can benefit the community, the agency, and most importantly the victims and families of victims who feel forgotten.

POLICE contacted two former supervisors of effective cold case investigation teams—retired Major Ed O’Carroll of the Fairfax County (Virginia) Police Department and former Sheriff of Douglas County, Colorado, Tony Spurlock—to discuss best practices for starting and maintaining a cold case investigation unit. Here are their tips.

1. Getting Command Buy-In

Starting a cold case unit requires commitment from the top brass of your agency. You have to have that buy-in from the chief or sheriff or other top brass and administrators before you start allocating resources, including personnel.

Spurlock says he believes one good way to gain buy-in is to not characterize the program as a cold case squad. “You need to start talking to people about putting resources to bear on solving murders and sexual assaults, more than talking about cold cases,” he says. “When you start using words like that at the highest levels, it tends to get the attention of the people who write the checks.”

One problem with saying “cold case” is there’s no strict definition of the term, according to O’Carroll. He says he doesn’t like the term because “cold” implies unsolvable. “What we are trying to do here is apply new technology and new investigators to these cases. Some of them are solvable.”

2. Finding a Leader

Any special police unit facing a difficult task like trying to solve decades-old crimes needs a leader who can inspire the team. O’Carroll says a cold case unit’s leader needs to know the capabilities of forensic science as well as how to lead the team. “You definitely need someone who is creative and has the ability to empower others,” he says. The leader also needs to be able to communicate with the public and the media about the mission. “You have to talk about these cases to generate interest in the community,” O’Carroll explains.

Leading a cold case investigative unit is not easy, adds Spurlock. “You have to be someone who wants to work hard and who doesn’t need instant gratification. This is a long haul and you have to be tenacious.”

3. Building the Unit

There are different models that have been used to build successful cold case units. The Fairfax County Police unit had great success bringing back retired officers, sometimes even the officers who worked the original cases, according to O’Carroll. “Our retiree pool that worked homicides and sexual assaults cared about the cases then, and they care about them now,” he says. The retirees were in addition to the full-time personnel involved, including detectives. “About 25 years ago we launched a cold case unit with a supervisor, four detectives, an analyst and a volunteer,” he explains.

The Douglas County Sheriff’s Office cold case unit had the following personnel when Spurlock was in charge: one detective, a civilian investigative specialist, and a crime scene investigator who had other duties. He also enlisted civilian volunteers, including two attorneys, a doctor, businesswoman, and technology expert who worked in the cellular industry.

“That team was very interesting,” Spurlock says of the community members. “They looked at cases through their expertise, and it was incredible to sit and listen to them. They came up with ideas that were later put into action by the detective or the investigative specialists.”

4. Special Training

Even though cold case investigation units are usually staffed with veteran detectives who have experience working on homicide cases, O’Carroll and Spurlock say the job requires special training.

“The mission on cold cases is different than anything else,” O’Carroll says, explaining that what makes it different is the forensic aspects of the job. “Technology is advancing. In just five years, science has gotten much better at giving us answers. Five years ago we did not have genetic genealogy. So we have to train to make sure we know what the laboratory can and can’t do.”

Training is also critical for civilian personnel and volunteers working cold cases. “We had five volunteers and we sent them each to different training,” Spurlock says. “I was even able to get them into basic homicide investigation training at the Colorado Bureau of Investigations so they would understand how law enforcement functioned.”

Spurlock adds that he sent the Douglas County SO’s crime scene technicians and evidence collection and analysis personnel to the most cutting-edge training available. “And that made all the difference because of what they learned and the contacts they made,” he says.

5. Case Selection

On average a little more than 50% of homicide cases in the United States are solved. That means any law enforcement agency that has been operating for more than a few decades has a sizable backload of inactive cases. So one of the first tasks faced by a cold case unit is determining which cases will get their attention.

Selecting cases for additional investigation is not about going after the most controversial or heinous crimes. It’s about choosing the ones that can be closed. “We focused on homicides and rapes,” O’Carroll says. “We had about a hundred unsolved homicides and about 600 unsolved rapes or sexual assaults.”

Four detectives and a support team cannot investigate 700 cases at the same time and accomplish anything. So the Fairfax PD’s cold case unit had to develop a formula for deciding which ones could be closed with further investigation. O’Carroll says the formula for determining which cases to pursue included availability of physical evidence for DNA, the total amount of evidence on file, and the availability of witnesses.

Spurlock says Douglas County used a similar kind of cold case triage. “We did a chart on every case that had physical evidence that could be used to extract DNA or there was some other kind of physical evidence such as fingerprints,” he explains. The cases were then assigned categories based ranked one to three, with three being the most likely to be solved.

6. Older Cases Can be Solved

When selecting cases for further investigation, both Spurlock and O’Carroll say that age of the case should not be a primary consideration. “Going by age is just not a good idea,” Spurlock says. “You want to go with the solvability factor.”

He explains that the “solvability factor” on two of Douglas County’s cases was very high, and one case was 35 years old and the other 40 years old. “Those are the ones we started with right off the bat, and we were able to solve them using DNA.”

7. Be Creative

Age shouldn’t be a primary concern when picking cold cases to investigate. But if the goal of your investigation is to charge the perpetrator, then you do have to be aware of the statute of limitation for the crimes you are investigating. That’s why so many cold cases tend to be about murder. In most jurisdictions, there is no statute of limitations for murder. The statute of limitations can be more complicated when it comes to rape and other violent sex crime and sexual crimes against children.

Fortunately, the statute of limitations is not always an insurmountable hurdle to investigating a case, identifying a perpetrator, and charging that person. Cold Case investigators have to look at all the elements of the case and be creative in their pursuit of solving the case and seeking justice for the victims.

Spurlock says the Douglas County cold case unit was once able to get around the Colorado statute of limitations on sexual assault by going after a serial rapist on another felony charge.

“We had a string of sexual assaults for about six months in 1995 in different jurisdictions. It took a couple of years for us to make sure that they were all the same or similar, then the case went cold,” Spurlock says. “When we looked at reopening them we realized we were up against the statute of limitations. The detective painstakingly read the file and found something that wasn’t documented in the original investigation. In one of those cases, the suspect moved the victim from place to place, which constitutes kidnapping in Colorado. That gave us the ability to pursue the case.”

Spurlock says the suspect has now confessed to a multitude of rapes in 1995. He is pending trial. “The DA can’t prosecute him on the rapes, but is prosecuting him on the kidnapping and extenuating circumstances.”

8. Starting from Scratch

Both O’Carroll and Spurlock say the best practice for investigating a cold case is to treat it like a crime that just happened. They argue against shortcuts. “You are starting this case from scratch,” Spurlock says. “The only difference is you don’t have a crime scene to drive to.”

Another major difference between a cold case investigation and a current crime investigation is that the original investigators become witnesses, if they are still alive. “As investigators we have a hard time stepping away from another detective’s work and then redoing it. We need to be adaptable enough to do that,” O’Carroll says.

Sometimes the original detectives join the team that is redoing their investigation. “They cared about the case then and they care about it now,” O’Carroll says. “If they are still alive, contacting them is part of our case vetting process.”

9. You Will Need Help

Very few law enforcement agencies have the resources to investigate cold cases without any assistance. It is likely you will need to work with other agencies surrounding your jurisdiction. You also may have to work with agencies outside of your area.

Another aspect of cold case investigation that may require you to seek assistance is that they can be expensive. DNA testing can be particularly pricey for cash-strapped local law enforcement agencies. Fortunately, there are resources that can help pay the bills. O’Carroll recommends Season of Justice and the Sherry Black Foundation.

Season of Justice is a nonprofit that provided funding for investigative agencies to help solve cold cases. It provides grants for advanced DNA analysis solutions such as genetic genealogy and next-generation sequencing.

The Sherry Black Foundation was created in 2017 by Heidi and Greg Miller as a way to share knowledge that they learned after the murder of Heidi’s mother, Sherry. The Foundation holds symposia to train investigators in evidence analysis, investigative techniques, and crime assessment. It also will consult on cases and will help investigators understand laws governing genetic genealogy investigations.

Major Ed O’Carroll of the Fairfax County (Virginia) Police Department (now retired). O'Carroll supervised the agency's cold case investigations unit.

Fairfax County PD

10. Victims and Survivors

Reopening decades old murder and sexual assault cases can be difficult for the investigators, the victims’ family and friends, and the victims themselves. Sometimes the survivors and victims are less than thrilled with the effort your agency has put into their cases and they can be upset about it. So you will need investigators who can empathize with them. “You have to be ready to deal with more than a decade of anger at the police department because they feel forgotten,” Spurlock says, adding that even if they are not angry, you are reopening their wounds when you reopen the case.

Cold case investigations can be especially emotional for victims of sexual assault, adds O’Carroll. “Recently, I met a woman who was brutally raped 25 years ago,” he says. “She shared with 248 people at a conference that she went 15 years without hearing from the police department that supposedly cared about her and her case.” He adds, “One of the things we have to remember is that it’s the victims’ case.”

Spurlock says despite the fact they may be angry that the police have not contacted them after the case went cold, reopening the case and solving it can help them find peace. “Survivors and victims are wondering if the bad guy is still out there and whether they are in danger even 20 and 25 years after the crime. So if you can solve it and tell them the guy is deceased or in jail that brings them great relief.”

And it’s not always about finding the bad guy. One of the most successful cold case investigations in Fairfax County was identifying a suicide subject with genetic genealogy 25 years after her death. “We gave her back her name,” O’Carroll says. “The brother of the deceased wept when we told him. He had always wondered what happened to his sister.”

Law enforcement officials who have questions about starting a cold case investigative unit can contact Ed O'Carroll, retired major Fairfax County (Virginia) Police Department at edocarroll@yahoo.com.

More Investigations

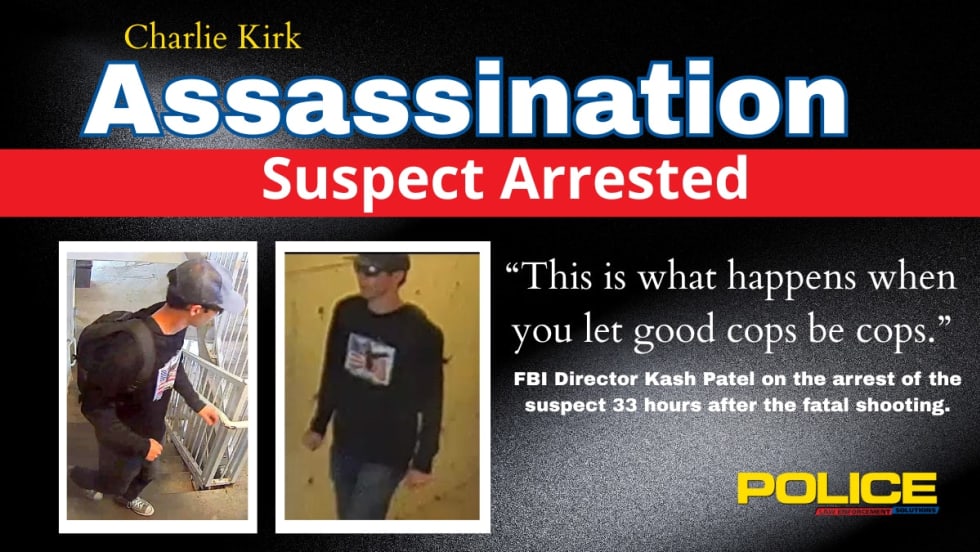

Suspect Arrested in Charlie Kirk Assassination

Authorities arrested a 22-year-old Utah man for the killing of Charlie Kirk just 33 hours after the assassination in what FBI Director Kash Patel called a historic time period. “This is what happens when you let good cops be cops,” Patel said.

Read More →

More Than 7,000 Tips Provided to Kirk Assassination Investigation

More than 7,000 tips were provided to the investigation by the day after the assassination of Charlie Kirk on a Utah college campus on Wednesday. The FBI has not received that much help from the public since the Boston Marathon bombings.

Read More →

Idaho AG Will Not Pursue Charges Against 4 Officers Who Fatally Shot Nonverbal Autistic Teen Armed with a Knife

The Idaho Office of the Attorney General has concluded its investigation into the fatal officer-involved shooting that killed a 17-year-old teen who was armed with a knife. Officers did not know the teen suffered from developmental delays, autism, and other conditions.

Read More →

The Role of Forensics in Disaster Victim Identification

Heidi Sievers, of Columbia Southern University, explains disaster victim identification and how scientific work bridges critical gaps when visual recognition, one of the least reliable methods of identification, is rendered impossible by the conditions of the disaster.

Read More →

Crimes Against Children Detective Named June 2025 Officer of the Month by NLEOMF

The case began in March and culminated with multiple search warrants and arrests on June 10, 2025. This case ran between Virginia and New York with multiple victims throughout the United States.

Read More →

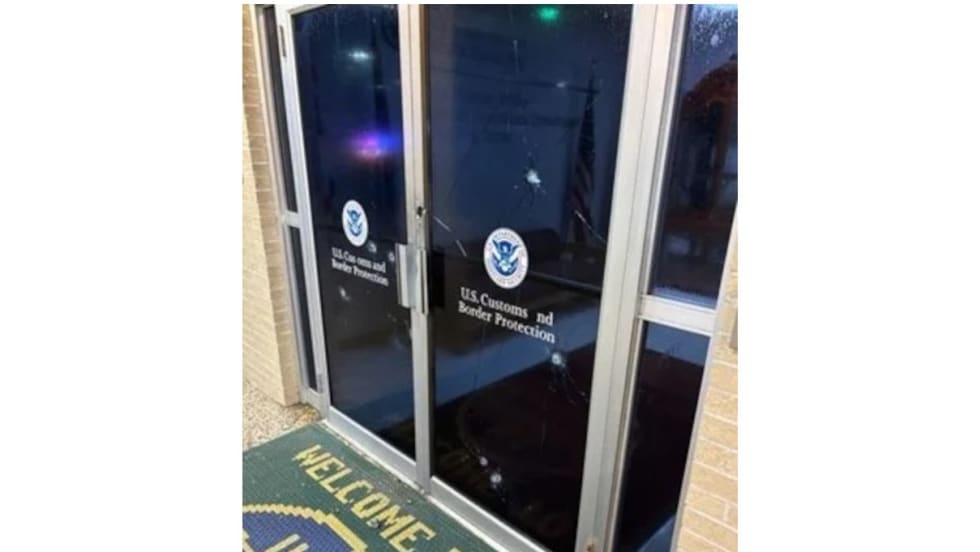

2 Officers Injured in Attack at Texas Border Patrol Station

A McAllen Police officer was shot in the leg during the attack. A Border Patrol officer and a non-sworn employee were injured, according to a Department of Homeland Security.

Read More →

Multi-State Law Enforcement Operation Rescues 70 Human Trafficking Victims

The operation involved the execution of 25 search warrants and disrupted business at 26 “illicit massage businesses,” the Human Trafficking Training Center reports.

Read More →

2 Ohio Officers Shot During Traffic Stop, Suspect at Large

According to the Franklin County Sheriff’s Office, the suspect has been charged with one count of attempted murder and two counts of felonious assault.

Read More →

DOJ Rescues 115 Sexually Exploited Children, Arrests 205 Offenders

“The Department of Justice will never stop fighting to protect victims — especially child victims — and we will not rest until we hunt down, arrest, and prosecute every child predator...,” Attorney General Pamela Bondi.

Read More →

Louisiana Lieutenant Killed by “Friendly Fire” While Executing Search Warrant

Lieutenant Allen “Noochie” Credeur, 48, was searching for a suspect wanted over a stabbing incident Monday afternoon around 1:30 p.m. when he was hit and mortally wounded by friendly fire, the department says.

Read More →