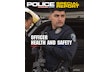

A GBI forensic biologist examines evidence for biological fluids.PHOTO: GBI

A GBI forensic biologist examines evidence for biological fluids.PHOTO: GBI

The Georgia Bureau of Investigation’s (GBI) crime lab, the second-oldest statewide crime lab in the country, receives more than 100,000 lab requests each year. With that level of caseload, the key to success is adopting technology to speed processes where possible.

The state crime lab, operated by the GBI Division of Forensic Sciences, first began processing evidence in 1952 and now has grown to include seven locations strategically placed around the state. The first crime lab providing statewide service was the Los Angeles Police Department forensic lab that opened in 1923.

“So, when you think about forensic biology, or DNA, any case that's going to need those services from those 159 counties, those are going to come to us. When we talk about drug chemistry, we're getting the overwhelming majority of those,” says Cleveland Miles, director of the GBI’s Division of Forensic Sciences. “We get about 110,000 requests a year. So that's a huge number of requests that are coming in and that's going to be everything from toxicology to blood alcohol, your drug identification requests, latent print examinations, firearms examinations, we're talking about all of those.”

Forensic Biology

The forensic biology section of the lab performs serological and DNA analyses of physiological fluids for the purpose of identification and individualization. The goal is to identify what type of body fluid is present and then, through DNA analysis, link that material to a specific person. In the most recently reported month, August, the crime lab received more than 4,000 forensic biology requests.

“We've managed to keep ourselves up to date when it comes to the testing of forensic biology. There's a lot of automation and robotics that are in the field now,” says Miles.

The GBI crime lab has robotic handlers to move liquids and samples through analysis processes and that is just a step in creating more efficient workflows and faster turnaround times.

“We're looking to develop a high throughput and that means processing a lot of samples at one time. We're developing a high throughput method for testing burglary samples, but we're also looking to move into doing the same thing for our sexual assault kits, to be able to test those in a high throughput manner, just so that we can stay on top of the caseload that's being requested of us,” Miles explains.

For collecting contact DNA, the lab has been using the M-Vac system for several years. After samples are collected, robotics and technology take over processes that years earlier were labor intensive for scientists.

When Miles first entered the field more than two decades ago, scientists still collected and used processes by hand to quantify the DNA. It took a long time.

“You would work this process to quantify the DNA, it would take you hours, it would take you three hours and you're constantly checking and going back and forth with the sample. It was a great process for what it was at the time,” Miles recalls. “Now it takes a quarter of the time.”

A lab scientist now can place the samples on an instrument, walk away, and come back later to check on them.

“A lot of things have gone towards automation, the technology has allowed us really to move the field further,” he says. “It allows us to do things efficiently and reliably. And so that's really what is happening for the field across the board, but especially in DNA.”

With more automation and faster turnaround times, the lab can attack case backlogs.

“Our sex assault kit backlog has steadily decreased over the last two years. That was really a big point for us to try and get backlog under control,” says Miles.

While the lab is focused on getting the high-throughput method into place and hiring and training new scientists, it is also outsourcing some of the workload to other labs.

Cold Case

In September, the GBI identified who killed Stacey Lyn Chahorski. The decades-long case was solved in collaboration with the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s crime lab, which had access to resources past what the Georgia crime lab could offer.

The body of the missing Michigan woman was discovered by deputies in northern Georgia in December of 1998. More recently, the GBI contacted the FBI about the possibility of using a new type of genealogy investigation. With that technology, her identity was uncovered in March of this year. The same tech also revealed her killer.

Henry Fredrick Wise was identified through genealogy DNA as Chahorski’s killer. However, the truck driver and stunt driver died in a 1999 car accident at Myrtle Beach Speedway, SC. He had numerous arrests before his death, but in those days DNA was not collected.

The FBI used Othram, a lab specializing in this advanced testing, and received positive results on June 13, 2022. The GBI began to interview family and obtained DNA swabs for comparison to the profile created through genealogy DNA and identified Wise.

“It's great when we're able to partner with law enforcement agencies to really take a look outside of the normal box, and to partner with other agencies and laboratories to try and get an answer and get some of these cases solved,” Miles says.

A GBI trace evidence scientist uses a microscope to view paint samples.PHOTO: GBI

A GBI trace evidence scientist uses a microscope to view paint samples.PHOTO: GBI

Latent Prints

Examiners in the latent print section of the GBI crime lab specialize in analyzing impressions produced by the ridged skin on human fingers, palms, and soles of the feet. They have various techniques at their disposal including use of chemicals, powders, lasers, alternate light sources, and other physical means to detect and analyze latent prints.

“A lot of our latent print examiners are going digital and so those are some of the new technologies that are in place that we offer. We have quite a caseload in latent prints, but we have the ability to really handle it better than in some of the other departments because we have staffing that's appropriate for the caseload that's coming in,” he says.

A GBI forensic chemist performs an extraction looking for the presence or absence of an illegal drug.PHOTO: GBI

A GBI forensic chemist performs an extraction looking for the presence or absence of an illegal drug.PHOTO: GBI

Forensic Chemistry

The primary function of the chemistry section, which had 3,902 requests in August, is to analyze evidence to determine the presence or absence of controlled substances. The state crime lab chemists then also provide expert testimony to the courts and supply the courts and other state agencies with factual drug information.

Examiners identify substances submitted by law enforcement, determine purity of cocaine and methamphetamine when required, identify THC in oils and food products, and incinerate drug evidence as requested by law enforcement.

“We have, as you can imagine, quite a lot of drugs that come to our laboratory for testing — that's going to be fentanyl, methamphetamines, cocaine, heroin, the whole gambit,” Miles says.

But past testing drugs, another key function of the forensic chemistry team is testing fire debris from suspected arson cases. At a fire scene, a fire investigator will collect an evidence sample of debris, carpet, wood, etc., and package it into an airtight container such as a sealed jar or metal can.

Once at the lab, examiners will extract any volatile components that may be present in the fire debris sample. The extracted sample is then analyzed on a Gas Chromatograph Mass Spectrometer (GCMS).

Firearms

The firearms and toolmark section’s examiners provide scientific support to all law enforcement personnel. Capabilities include determination of the type of firearm that a bullet or cartridge case was fired from, whether a bullet was or was not fired from a suspected firearm, whether a cartridge case was or was not fired in a suspected firearm, whether a tool found in a suspect’s possession was or was not used to cut, scrape, pry, or pinch evidence material seized from a crime scene. Examiners also can find the original serial number of a firearm or other metal object after the number has been obliterated, if gunpowder is present on a victim’s clothing or on other evidence that may have been the target of the suspect, and the distance from the muzzle of the firearm to the target at the time the firearm was fired. However, for the later, the firearm must be present for testing.

In the firearms department, the GBI has hired what Miles terms as a good bit of staff over the last year and a half. But technology is also making firearms analysts' tasks easier.

“One of the things we're doing with firearms is moving to 3D imaging,” Miles says. “That's really going to help our process. What that allows for us to do is have that record of this evidence without actually having the physical evidence.”

Miles provides an example of how this all works. If someone is stationed at a lab in the western part of the state and working with someone in the main lab in Atlanta, that digital scan can be shared.

Toxicology

The toxicology examiners provide state and local law enforcement officials and medical examiners with vital information about human biological samples and specifically whether drugs, alcohol, or poisons may have played a role in the commission of a crime or a death.

Medical Examiners

The medical examiner’s office provides complete forensic pathology services to 155 of Georgia’s 159 counties for deaths which qualify as coroner cases under the Georgia Death Investigation Act.

Autopsies are conducted by GBI medical examiners at the headquarters lab in Decatur and in the regional crime labs in Macon and Pooler. Staff consists of forensic pathologists, death investigation specialists, and administrative staff.

“We have full time doctors, we have some part-time doctors, that perform the autopsies for our medical examiner's office. We are in the process of recruiting and hiring additional doctors that are needed,” Miles says.

Judicial Obligations

Examiners and scientists are typically under a subpoena from some county in Georgia every workday of the month, says Miles. Think of it this way, he explains. If a chemist releases 70 reports a month, the corresponding court cases build up fairly quickly.

“The great thing about it is a lot of times you're not having to go in to testify, but you will provide testimony pretty much on a regular basis. We have a great relationship where we work with district attorneys’ offices, or whomever subpoenas us, to try and work out a schedule to allow for the scientists to be there to testify,” he says. “I will tell you that we've had some scientists who've had to go to three different counties in one day to testify, myself included, from time to time. It doesn't happen often, but it can happen.”

But, that leads to another advantage of having the crime lab locations scattered across the state of Georgia. Typically, if court travel is required, the court is usually nearby.

Crime Scene Specialists

Although not part of the crime lab, the GBI does place nationally certified crime scene specialists around the state in the agency’s regional offices. They are special agents like their peers, but with a duty assignment specialized in gathering evidence at crime scenes. Two are stationed at each field office with the number of crime scene specialists increasing to four at the office in the Atlanta area.

GBI Special Agent Daniel J. Burlingham, left, and GBI Special Agent Carl D. Murray provide specialized crime scene skills to assist fellow agents and local agencies in their assigned region of Georgia.PHOTO: Wayne Parham

GBI Special Agent Daniel J. Burlingham, left, and GBI Special Agent Carl D. Murray provide specialized crime scene skills to assist fellow agents and local agencies in their assigned region of Georgia.PHOTO: Wayne Parham