The girlfriend was provided with a “burnout phone.” A burnout phone is one that would be operational for a few months before being burned out. By that time the bill would have grown to many thousands of dollars, which they had no intention of paying.

In part one of this blog, I discussed the steps my unit had to take to set up a wiretap on phones in unit 1750 of the Los Angeles County Jail. Our target was a Mexican Mafia shot caller.

As I discussed earlier, wiretapping operations are labor intensive. And we needed lots of help for our surveillance of the phones in unit 1750.

We borrowed some electronic monitoring equipment from the FBI. We also borrowed personnel from the jails, court services, OSJ, JIU, Metro, and Fugitive details. I was assigned as the sergeant and supervisor along with three of my prison gang detectives. Monitoring began on March 20, 1996.

At first this money and manpower drain fueled some department opposition to our groundbreaking attempt at a state wiretap. And my own experience suggested that wiretaps should be of short duration or they get too big and complicated. But soon we had mountains of intercepted communications and lists updating the "green light" hit list, which would lead to the prevention by jail staff of at least 44 attempted jailhouse hits.

We also began intercepting on the wire a daily "court list" of loyal Sureños and the courts they would appear in. The gang members and their attorneys would request court orders for civilian court clothing. This would commonly be granted by the judges. Mexican Mafia associates would send a seamstress to buy the gangster pants and shirts suitable for a court appearance. The seamstress would use a steam iron to press a quantity of tar heroin between two sheets of paper and then cut the packages to fit the seams, collars, and cuffs of the clothing. She would then re-stitch the whole thing up and present the pressed and cleaned clothing to the inmate's girlfriend or attorney.

The morning of the inmate's next court appearance the clothing would be examined by the bailiff—who would notice nothing unusual—and given to the inmate. The Sureño gang member would be escorted to a cell to change clothes.

The inmate would then do a quick stripping of the dope out of the hidden seams, balling it up and "keestering" it up his anus before putting on his new court clothes. This dope would later be delivered to trustees working the returning court lines and passed up to the Mexican Mafia gang members in unit 1750 or one of their shot callers.

This court-ordered civilian clothing exchange was responsible for a large part of the drugs entering the jail system. Once we understood the system they used, and the Sureño court list, we seized more drugs in the relatively short duration of the wire than the entire staff of jail and court deputies had recovered in 20 years.

Dirty Attorneys

Not all of it was found on inmates.

On Aug. 28, 1996, in a capital death penalty gang murder case, an attorney attempted to hand his Sureño gang member client some legal papers in a Torrance, Calif., courtroom. Based on the wire-intercepted Sureño court list, we had pre-warned the bailiff that someone would attempt to pass drugs that day.

While inspecting the paperwork the bailiff found a lump of tar heroin pressed between two legal pages that had been carefully glued together. The attorney was arrested for possession of heroin.

Dirty Deputy

In another case we set up a video surveillance camera on a courtroom holding cell for women inmates because we expected drugs to be delivered there. Instead we caught a court deputy having sex with an inmate.

It worked like this; gang-related women held in the women's Sybil Brand jail facility would call (on an unmonitored phone) the court deputy's desk. They would tell him that they had a new girl who wanted to have sex with him. They would give the deputy the inmate's booking number, and the court deputy would request her for a court appearance in his court. Since she really did not have an appearance she would remain in the holding cell until she was alone. The deputy would have sex with her in the cell and leave the payment, a small amount of drugs for her and the girls at Sybil Brand. That was the end of his career.

Communicating Threats

We also found that inmates were routinely using the county phones to call and intimidate witnesses in their own cases or for their homeboys' cases.

They would call the county inmate information system to obtain information or locations of rival or targeted individuals in the jail system. We were intercepting so much criminal information that the case expanded to several more lines. The department bosses who had been reluctant to back the state wire now insisted that the wire not be shut down.

Herculean Task

The California wiretap procedure required us to report in writing to the presiding judge all pertinent calls for his review and assessment every 72 hours. The meticulous attention to detail, the labor needed to monitor and transcribe the many hours of tapes, and the expense of overtime and equipment maintenance became overwhelming as the additional lines multiplied. We could have indicted hundreds of gang members, but the logistics of this huge prosecution was mind numbing.

The most important wire interceptions involved the Mexican Mafia's "green light" lists also known in the jail as "hard candy lists." These were inmate transcribed hit lists, giving each intended victim's name or gang moniker and his street gang affiliation.

A keestered jail knife or "shank" is often called "hard candy" because, according to a gang member I once interviewed, "it looks like a Baby Ruth candy bar when it first comes out." But it is "hard" and intended for the murder of those listed on the "hard candy list."

Legal Liabilities

There were also some legal liability issues that arose. The officers working the wire room often had to take immediate action when gang members inside or outside of custody talked about acting on the green lights. However, this intervention could not expose the fact that a wire tap operation was the source of this information.

This is where the legal term "wall" or "Chinese wall" comes from. We would often hand off these situations to the Prison Gang Surveillance Team, giving them only very limited information to protect the wire. They would then develop "probable cause" to initiate a traffic stop or parole search of either the intended victim or the suspects in order to prevent the hit.

Defense discovery in these handed off cases was thus legally "walled off" from the wiretap. We became very creative in making these interventions seem like accidental or just unlucky circumstances. We used the jail bureaucracy, ruses, and outright lies to stop impending murders and attempted murders. But sometimes—a very few times—we were too late.

Three Way and Burn Out Phones

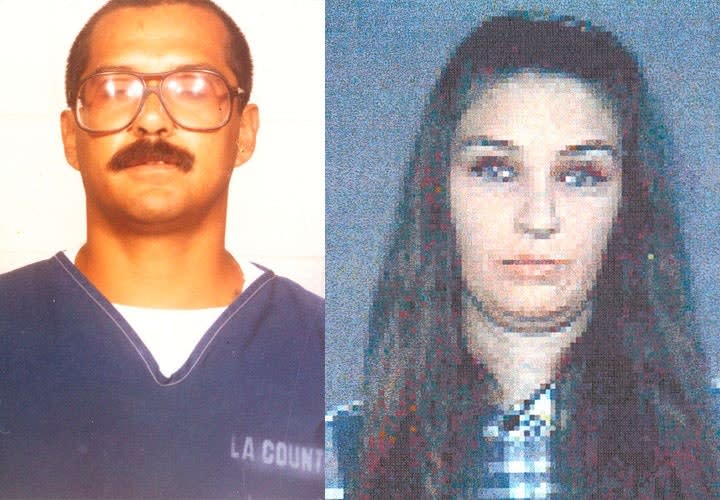

The primary suspects soon were identified and linked in a web of intercepted criminal conspiracy communications. At the center of the web was a lowly Sureño inmate's girlfriend, Anna "Banana" Reed.

Anna was a third party conduit to this criminal communication system. She linked the gang members inside to those operating outside. This is called a "three way."

She was provided with a "burnout phone." A burnout phone is one that would be operational for a few months before being burned out. By that time the bill would have grown to many thousands of dollars, which they had no intention of paying. When the phone was burned out she would receive another number.

All telephone calls from the county jail at this time were collect calls. "Anna Banana" was instructed to accept all incoming collect calls. The Mexican Mafia-affiliated inmates and associates all over the jail system were given Anna's telephone number to report in. Frank "Bosco" Marquez from Varrio Norwalk, who was at that time a Mafia associate, was Anna's primary contact in the jail. Bosco was housed in 1750 with Mexican Mafia member Luis "Pelon" Maciel from El Monte Flores.

Anna also had contact with shot callers at Pitches Detention Center and with Mexican Mafia members Daniel "Popeye" Roman and George "Huero Caballo" Gonzales in Pelican Bay State Prison. Mexican Mafia members on the street who were also intercepted were Armando "Perico" Ochoa, Robert "Robot" Salas, Juan "Topo" Garcia, Mariano "Chuy" Martinez, and associate Albert "Babo" Juarez.

Mi Vida Loca

Several of the females involved in this wire tap case were from the Echo Park area and you can see what they looked like by renting the movie "Mi vida loca" (1993). Director Allison Anders compiled her script from anecdotes from real girl gangs. She also cast genuine "gangbangers" in the film.

No Sunset

As a result of this state wiretap case, there were many convictions of gang members from many different gangs, with Frank "Bosco" Marquez and Anna "Banana" Reed receiving the bulk of the time and many multiple life sentences.

Also, the Los Angeles County Board of Commissioners finally capitulated, and an inmate telephone monitoring system compatible with the California Department of Corrections system was installed and activated in L.A. County jails. In addition, our case prevented "The California Wire Tap Act" from being sunsetted out of existence.