Every victim or witness had heard the stories in the ghetto about gang retaliation against those who were foolish enough to snitch on gang members. Most of these stories were only urban legends that grew with each telling. Some were absolutely true. Gangs do target witnesses.

Taking a criminal gang case to court involves many special considerations that could imperil the case. All the legal and procedural issues common to other criminal prosecutions remain, but added to these are the particular problems associated with gangs. It's also an officer-safety issue.

One of the original motivations for the establishment of dedicated gang units in Los Angeles was the lack of successful prosecutions experienced by the regular detectives. These non-gang detectives operated with an understanding of the legal system as it applied to the people living in the normal American culture. The problems occurred when this same legal system was applied to people of other cultures, especially when applied to the deviant criminal gang culture.

The first problem they often encountered was the lack of witnesses willing to be witnesses in court. Even the victim of the gang could develop amnesia, or even deny that the known perpetrator was involved. Sometimes this was due to cultural distrust of police and the legal system that emigrated along with the witness from another country. But harder to overcome was the accepted drug and gang cultural commandment of "Thou shall not snitch." I remember that when trying to convince a witness to trust the system in these gang infested communities the reply would often be, "You go home at night, but we have to live here."

Every victim or witness had heard the stories in the ghetto about gang retaliation against those who were foolish enough to snitch on gang members. Most of these stories were only urban legends that grew with each telling. Some were absolutely true. Gangs do target witnesses.

In many gang trials, the witnesses are often required to sit outside the courtroom in the hallway. This is also a popular area for gang members to threaten witnesses verbally or non-verbally. This was especially true at the Los Angeles East Lake Juvenile Court. I'm sure that numerous gang criminal cases were lost when witnesses were intimidated by gangs in the court hallways.

Sometimes these intimidating threats are delivered by telephone, sometimes directly to the victim, but more often to the witness's friends and family. Unscrupulous defense attorneys share the names and phone numbers and other information gleaned from police reports and discovery paperwork with their clients or the defendant's family. Copies of these reports and transcripts are used as "death warrants" in gang culture against the victim and witnesses.

Another problem was the confusing bureaucracy of the system and the rude beauracrats that expected everyone to know what to do. As officers of the court, prosecutors, and gang detectives, we understand the general procedure and methods of our judicial system. Hell, even the gang members understand how it works. But to the average law-abiding citizen the judicial bureaucracy is a frightening mystery.

In the field, avoid drawing any attention to anyone who is cooperating in any gang investigation. When you get a chance, before the trial, explain to the witness if the witness will be required to appear in court, and how many times. Offer the witness a witness relocation or protection program if available. Also tell the witness the truth about what you can and can't do. If you promise something, keep your word. As a gang investigator, your reputation will soon reach the ears of the community you serve. Keeping your word will build the trust that will convince others to come forward.

When the eventual court date comes, a good gang cop will make sure that the witnesses is familar with the location of the court, where to park, a safe way to get there, another person accompany them, your cell phone number, and has the victim assistance contact information. If necessary, pick them up and deliver them yourself.

Remember, you're also a witness, and your security must also be a consideration. Don't let your guard down because you're in the familiar and seemingly secure venue of the courtroom. When leaving your driveway on the day of an important gang trial, you should scan your neighborhood. Beware of where you park your car and who follows you as you walk to the court elevators.

During the federal RICO trials against the Mexican Mafia in Los Angeles, members of the radical Brown Berets and other gang activists demonstrated against the police in front of the courthouse. We had to walk past this Mexican Mafia support group to enter the courthouse.

Although LAPD and LASD officers were part of the Metropolitan Violent Gang Task Force and carried federal identification, we were required to lock our weapons in gun lockers before entering the federal courthouse. The FBI and other federal agents were not required to disarm. This was an insult. The local gang members rarely recognized any federal agents, but they most certainly recognized us. The LAPD and LASD officers complained to the FBI about being disarmed, but this requirement continued.

During the trial, FBI agents told us to keep our weapons and intervened with the federal court officers, allowing us to remain armed. As we sat in court, I noticed many more FBI agents and several extra bailiffs. A clear ballistic plastic partitan partially shielded the audience from 13 Mexican Mafia defendants.

This trial was one of the most high-security trials in Los Angeles history. On this day, there was even more tension. We later found out that the federal agents had received information that the Eme defendants had a gun smuggled into the federal detention facility. They feared a possible courtroom takeover or escape attempt. We weren't told about this until much later, but this was the reason we weren't required to check our pistols that day.

Because trials are supposed to be public, family members, gang members and other sympathetic gang supporters usually attend the trial. Our primary cooperating witness, Mexican Mafia member Ernest "Chuco" Castro's brother, Eddie "Deadeye" Castro, sat in the first row in front of the witness stand and "mad dogged" his brother as he testified on the stand. This was an unspoken death treat in any gang culture but the U.S. attorney didn't object, and the judge allowed it.

During the Mexican Mafia RICO trials in January of 1996, I was living in San Bernardino County. My personal vehicles were registered to a sheriff's facility, and my address was a post office box in La Mirada. If you called the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department and asked for me, they would have told you that I didn't work there.

But one day while I was at a doctor's appointment a brand new white Mercedes pulled into my driveway and a suspicious couple approached my front door. The woman was Latina and well dressed, but the male was a short thug-like Latino with a pock-marked face. They knocked and asked my wife if Sgt. Richard Valdemar lived there.

My wife played dumb and after deflecting their questions told them they should go to the police station if they wanted to talk to a policeman. Behind the screen door and behind her back she held a loaded pistol. They left angry and confused, but they left.

Later we found out that the male was Isaac Gillen, a paralegal and an investigator for the Mexican Mafia. He was admitted to the California Bar in May of 1998, but was indicted in the June 2009 federal 18th Street gang indictment. The superseding federal indictment charging Gillen as a co-conspirator alleged that he laundered money, maintained business partnerships with gang members and deposited over $27,500 in accounts of gang members housed in a supermax facility in Florence, Colo. He is now an inmate himself.

The suspected source of the leak of my personal information was the wife of Mexican Mafia member Mariano "Chuy" Martinez's wife who worked as an administrator in the Kaiser Permanente health-care system. Although my personal information was dutifully shielded by LASD, the department faithfully updated this information to my health insurance plan every six months.

Sometimes threats are made against the jurors, judges or the district attorney. In this modern information age, identifying information and addresses and phone numbers are obtainable by almost anyone.

I spent lots of time in courtrooms as the investigator or the gang expert, but the Compton Courthouse was one of the worst. In one incident, a defendant who had been released on his own recognizance (O.R.) showed up in court and passed through the metal detectors at the doors. But inside the courtroom he produced a homemade sharpened wooden dagger and attacked in a wild frenzy. The court deputies managed to subdue him but not before he inured several people.

In another courtroom incident, a Mexican Mafia associate and Tortilla Flats gang member nicknamed Midget was seated and handcuffed at the defense table. He was somehow able to remove a small razor blade that had been secreted under his eyelid. He slashed the face of his defense attorney "because he could not reach the prosecutor," he said later. His true motivation was to "catch another case" to delay his transfer to state prison. He wanted to stay in the county jail in order to find and "hit" some enemies of the Mexican Mafia. This is called "putting in work" and would enhance his standing with the EME when he finally made it to state prison.

After this incident, I was sent to brief the court deputies and district attorneys about how this could have happened and why? The DAs thought that the Mexican Mafia had threatened them because of their prosecution of gang members under California's three-strikes law.

I took copies of the Sureño's reglas. These are 29 jail-house rules set by Mexican Mafia shot callers regulating the conduct of Southern California Latino gang members. All gang members are required to memorize these reglas. Rule number 24 reads, "Mandatory to 'pack' dulces (slang for knives) to court, all homies under 30 years old. All blasting (stabbing) must be reported, ASAP, no ifs ands or buts. If courts are hot, that should also be reported." This meant that every loyal Sureño, under 30 years of age, was required to pack a weapon to court.

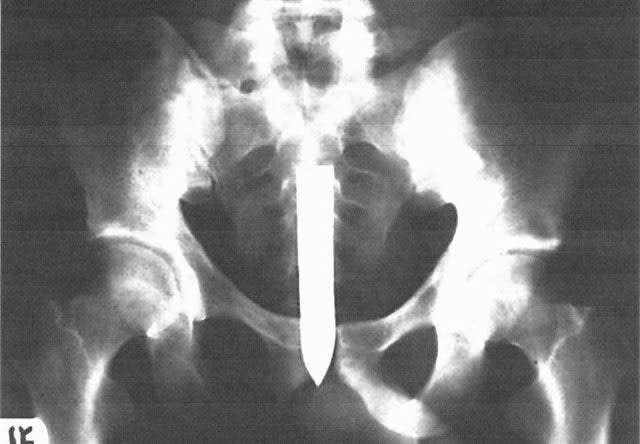

I also brought an x-ray of a sizable dulce shank packed in a Latino gang member's rectum. Gang members believe the courtroom is potentially a very dangerous place.