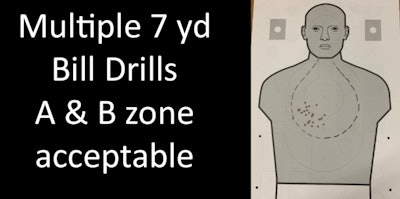

During presentations, Dawn Davis uses the above image to illustrate that a student’s shot placements are “good enough” when they land in the A and B zones of the target. An instructor should see this as a success and later can coach the shooter on moving the groupings toward the center of the target.PHOTO: Dawn Davis

During presentations, Dawn Davis uses the above image to illustrate that a student’s shot placements are “good enough” when they land in the A and B zones of the target. An instructor should see this as a success and later can coach the shooter on moving the groupings toward the center of the target.PHOTO: Dawn Davis

As a young officer Dawn Davis struggled on the range, but those struggles shaped how she approaches her job now as a lead firearms instructor at the Department of Public Safety Standards and Training (DPSST), Oregon’s police academy.

About seven years ago Davis retired from the Albany (OR) Police Department after 25 years of service and started working part time at DPSST in the scenario village as an evaluator and stayed in that role for about a year. Her goal was to get into firearms. When there was an opening to shadow a firearms instructor, she did and then trained to become one. She has worked exclusively in the firearms arena since, is one of only three fulltime instructors at the academy, was named the 2019 NRA Law Enforcement Firearms Instructor of the Year, and presented a class on improving your shooters at the International Law Enforcement Educators and Trainers (ILEETA) annual conference earlier this year.

“You’re an instructor because you're giving out some information, but then you're also a coach in that you're helping facilitate the learning of that information,” she says. “Here at DPSST, we’re striving to change the culture so that it is more of an investment in the instructors in how we deliver the information to our students. I think that culture really has an impact on not only who's working for you as your instructors, but how it's accepted by the students here.”

SHAPED BY STRUGGLES

The way Davis approaches her teaching methodology as a firearms instructor developed out of her struggles at the range when she was a young officer. The way she tells it, those were tough times.

“As a new officer, and somebody who hadn’t spent any time around firearms, for many years I was quite frustrated with the range. I was frustrated with the instruction that I received, and I dreaded going. I didn't like it and I felt quite a bit of shame surrounding my performance,” Davis says. “That was not conducive to me learning or getting any better and I just kept hearing the same things over and over and over again from the instructors.”

For a young Davis, the instructors kept using range language and terminology. She sees that as a detriment to teaching others to shoot and prefers common language that a new shooter can more easily grasp.

She said instructors would use words such as “smooth, stop jerking, stop slapping, and surprise.” An experience shooter may understand that lingo, but that does not mean every officer or student will grasp the words and how to take them as instruction.

“I didn't understand. It was a foreign language. If you don't speak that language, it's really hard to get any better and nobody explained the language to me at the time,” she says.

Davis says she is often asked what changed and when she started becoming a better shooter. She cannot pinpoint a single pivotal moment along that path, but the transition started when shooting became fun and there wasn’t as much judgment. For her, she relaxed and enjoyed shooting when at the range with fellow detectives that she worked with at her department.

“Once we started shooting just to have fun and I wasn't being judged for my performance but rather being given tips to make it better and I wasn't feeling that shame because I wasn't getting it exactly like how they do it, then I started getting better,” Davis recalls.

Earlier in her career she was at the range with an instructor, who now she has known for years, practicing 50-yard precision shots. Davis encountered a Phase 1 malfunction. She promptly and efficiently cleared it, but the instructor’s encouragement sticks with her to this day.

“After I cleared it, I heard him say ‘Beautiful, the gun did not move in your hand when you hit that Phase 1’,” she says. “I kind of felt like I had arrived at that moment.”

NO ASSUMPTIONS

Her transition from new shooter to confident shooter, including experiences of her struggle with those early instructors, stays with Davis now in her role at the academy as she teaches more than 600 individuals on the range each year. Most of those spend 60 hours with her.

“I'm on the range every single day with a bunch of different personalities and abilities. How we talk to them and how we perceive them just when first coming in, I think it's huge to make them want to come back,” she says. “When they're leaving a four-hour session, if they leave with a smile on their face, we've done something right. It doesn't necessarily mean that they were successful in everything that they did, but they knew that they weren't judged for it, and they were able to shake it off and know that ‘Hey, tomorrow's another day and we're just going to keep working on what we need to work on’.”

So, how does Davis approach instructing a shooter?

She said instructors should not pigeonhole students. Traditionally its easy for instructors to pre-judge whether someone looks like a good shooter or someone who will struggle. Davis says that is only human, but “leave it at the door.”

Sometimes instructors may think a female will not be a good shooter, but that assumption should be avoided. On the flipside, Davis says often a man will arrive at the range “all kitted out with his operator stuff” and instructors may think he won’t need as much attention. She says that absolutely is not the truth. Davis says just because someone has experience shooting does not mean they have good habits – they can always get better.

“So that's the first thing. Once that implicit bias is off to the side and once we establish an environment that doesn't limit our students, I think that how we deliver our feedback is hugely important,” she says.

FEEDBACK

Feedback is vital, but feedback does not only come from the instructor. Extrinsic feedback, intrinsic feedback, and broadband feedback are all part of leading a shooter to become better, Davis says.

Extrinsic feedback comes from the outside. That is not only where hits land on the target, but also feedback provided from an instructor.

Intrinsic feedback is what the shooter feels. When shooters can start self-diagnosing, they are on the road to improvement. However, Davis cautions that intrinsic feedback can become detrimental when a shooter focuses too hard on feeling what they are doing as they shoot. A balance of feeling what they are doing and shooting naturally works the best.

She recalls her early shooting days when in her head she constant heard “sights and trigger, sights and trigger.” Davis says she was so focused on trying to achieve the perfect front sight picture that it caused her to move the gun too much while firing and other components of her shooting suffered.

“So, we have to find that balance between when I can feel that I'm in that sweet spot and I can just press the trigger steady, consistent, straight to the rear,” she says.

She explains bandwidth feedback is when you accept that “good enough is good enough” such as when shooting multiple Bill drills at seven yards. Often during presentations to other instructors, Davis will share several images of targets to illustrate her point.

If she tells her students placing shots in the A and the B zone is good, then if that is where they land their shots, she has to be good with that. If she tells them A/B shots are good, then it is good enough even if the shots are a little off center. An instructor can make notes and help the shooter later refine the impact area and groupings.

“You have to be careful what you practice, because that's what you're going to learn. So, if you spend all your time moving that trigger very slowly to the rear so that you can have that tight group, what are you training your finger to do?” she says. “We don't have the time or the luxury to look at sights, nor will we focus on sights if somebody's trying to kill us. We're going to focus on that threat.”

When more experienced shooters shoot Bill drills, she encourages them to miss. With that, she means for them to push past their speed limit even if that causes an occasional shot to miss the A/B zone.

“When I talk about speed, I'm talking about the rate at which we can make combat effective shots,” she says. “In law enforcement we absolutely are going to be successful without being perfect. We don't have the time or the luxury to spend a lot of time getting that sight picture and pressing that trigger as slow as possible to the rear so that we can have that perfect shot. We're training our police officers to shoot to save lives, their own or somebody else. That happens very quickly. We don't get a timeout.”

DELAY COMMENT

Davis uses the WAIT acronym, which stands for Why Am I Talking? That acronym serves as a reminder for an instructor to pause, or wait, before addressing a student when they complete a drill.

Davis hopes instructors will delay providing feedback or coaching after a shooter finishes and relaxes. She says too many times as soon as the shots are fired, the instructor is too quickly in a student’s ear. Davis says it is better to delay comment and watch for the student to re-holster, relax their shoulders, let out a deep breath, or provide any other signal that shows they are complete with the drill and ready to receive feedback.

“Now they can accept what you have to say. If you just start talking, they're still in the moment that they just shot,” she says, as she continues to explain how the student should do most of the talking. “It is just like a police interview? We should be hearing more from them than they hear from us.”

BLOCK TRAINING VS RANDOM SPACE TRAINING

Davis says most firearms training in law enforcement is geared toward shooting qualifications. In her state, that course of fire begins at the 25-yard mark and moves in to the 3-yard distance. But no shooting they ever could face on duty follows that example.

“But truly, that does not set them up for success. Where the true test comes in is on the street. So, we want to get rid of that block training, you spend a certain amount of time shooting from each one of those stages until it appears that your shooter has mastered it. It's the illusion of learning,” she says.

Davis equates this regimented approach to training as cramming for a test and an instructor may think they have fixed a shooter, but if the student returns several days later to shoot the same drill performance may not be the same.

“It’s a qualification course. It's not what's going to happen out on the street. So, let's actually go into random and spaced training and some contextual interference so that they have to solve these problems mentally. So that's what we're doing now and we're still teaching all the skills that would be included in the qualification, but we're doing it in a different way,” Davis explains.

When she first became an instructor, students would spend eight hours a day for five days on the range early in the academy. She said that was too much for them to absorb and there were no sleep cycles for them to encode and solidify what they learned into their brains. Now they have shifted to random and spaced training in which they may focus on only one or two drills and then move on to something different.

“Their brains are constantly being engaged in different ways, even though we're including the stuff that they've already learned,” she says.

Every manipulation of the handgun and every draw should become System 1 thinking, thereby making all actions automatic and intuitive.

“So, we randomize what they do at different yard lines. Oftentimes, we'll ask them to do different courses of fire at a distance that’s further away and/or closer, and sometimes it's both, than they'll ever see in the qualification course,” she says.

There is an easy illustration she tends to use as she compares shooting to basketball. No basketball player gets better at free throws by standing in one place and only perfecting their shot from that one location on the court. A would-be hoops star will practice at various ranges and angles from the basket and not just take shots constantly at a measured distance from the free throw line.

“You put the traditionally-based-trained and the random-space-trained free thrower together and you'll find that the one who did random practice, and with contextual interference, is going to get more free throws than the ones who've just practiced at the free throw line,” she points out.