Let's take a look at some overlooked and undervalued areas of training and program development that departments and agencies can start to implement immediately to reduce training injuries.

In the beginning of my career as a training officer at the police academy, my primary goal centered around one word, output. For one hour, three times a week, I required every recruit to put out as much effort as was humanly possible. Warm-up and stretching was minimal, and my program lacked planning and attention to technique and gradual progression. My training sessions resembled the disorganized workouts of a rookie personal trainer.

Throughout the next few years of training, I witnessed numerous recruits from every academy class sustain a variety of injuries. These injuries included painful shin splints, pulled hamstrings, strained abdominal walls, torn knee ligaments, and a handful of heat exhaustion cases. I soon began to realize that there had to be a safer but equally demanding way to produce better outcomes with academy recruits while taking precautions to prevent injury.

After speaking with friends and colleagues in agencies and departments across the country, I learned the academy setting was not the only location where safer police training techniques were needed. Law enforcement agencies across the country are searching for ways to reduce training injuries among their officers and encourage their officers to adopt more healthy lifestyles. Programs implemented in these departments are made with great intentions but often times they need fine-tuning.

Let's take a look at some overlooked and undervalued areas of training and program development that departments and agencies can start to implement immediately to reduce training injuries.

Own Your Results

If your officers are experiencing injury rather than gain from their regular training programs, then, as a training officer, you have to ask yourself these two primary questions: What am I doing wrong? How do I fix it?

Complete ownership of your fitness program is what I am proposing. Every injury that happens during your training session is yours to own. If you take responsibility for your quality of training, the effort taken to reduce injury and increase benefit will greatly improve your final product and will be apparent at the end of your training programs.

So here are a few concepts or "take-aways" that will guarantee you produce better overall results and make department heads happier with you for not destroying their recruits and officers, who are hard to find, hard to train, and hard to retain over a 30-year career.

Educate Yourself

First, educate yourself in your profession as a trainer. Read and study as many books as you can find, and attend as many conferences by industry leaders in the field of strength and conditioning that your department's and your personal time will allow. Pay close attention to what the research and experts in the field have to share about training in the law enforcement profession and in special military units.

Here are some articles and books that I have found particularly useful.

An article published by Coach Rob Rogers titled "The Top Ten Things I Apply to My Training Program" is a great read to put things into perspective for you. Books such as Dan John's "Never Let Go" and "Can You Go," Mike Boyle's "Advances in Personal Training," and Dr. Kelly Starrett's research and writing on mobility, stability, and self-preservation are instructional gold that should not be overlooked. Gray Cook and Lee Burton's fieldwork and research in functional movement screening and movement pattern are industry standards that at a minimum should be reviewed. These coaches and authors are at the forefront in the field of strength and conditioning for tactical athletes, their writings are readily available, and all have a perspective worthy of review and study.

The education in training and human performance factors that you will receive from reading the works of these coaches and authors will help you build safer and more effective training plans. And in addition to a safer training program, you owe your officers the most current and relevant fitness training. The techniques they learn from you they will take with them to their future careers. By educating yourself, you can better educate them and that will have a positive impact for years to come on the future officers they work with.

Warm-Ups are Essential

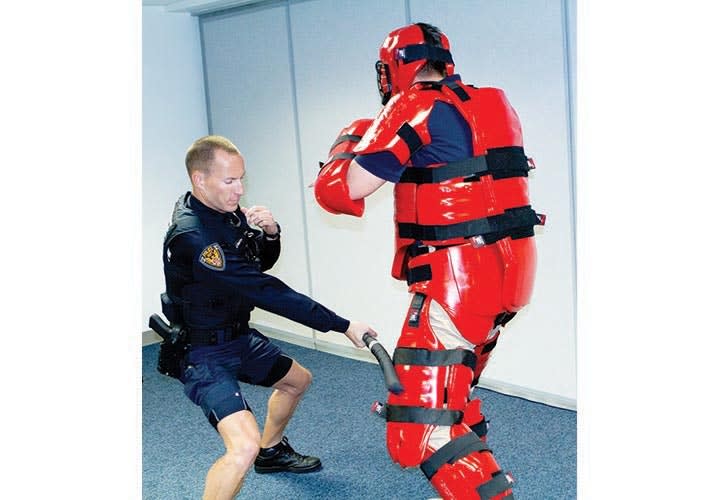

One reason why many officers are injured in training is that trainers are in a hurry to start working defensive tactics techniques because they know they have very little time to teach the concepts. Because of this ticking clock, they often skip warm-ups in an effort to pack in more training in the allotted time. This is a dangerous mistake.

You need to incorporate proper warm-up procedures before every workout. The system I have consistently utilized is borrowed from strength and conditioning guru Mike Boyle of Mike Boyle Strength and Conditioning.

Mike Boyle's warm-up is made up of the following components: foam rolling major muscle groups, static stretching, and dynamic stretching, to be done in that order. Many professionals in the field have completely erred in their understanding of static stretching and its usefulness along with foam rolling. Boyle, who has coached world-class athletes to help them reach their full potential, is author of several books. I have personally found the warm-ups described in his "Advances in Functional Training" to be very useful for law enforcement training. You can learn more about his programs at http://www.bodybyboyle.com.

Technique Over Reps

Focus on proper technique instead of high reps and rushing to beat the clock. If you fail to focus on technique when you begin to add load (weight) or stress (time), injuries fall from the sky like hail from a Midwestern thunder storm. This hailstorm of injuries can be avoided if sound techniques of exercises are emphasized in the beginning and throughout your fitness program.

Establishing a substantial foundation to build from will prevent officers from going out on medical leave in the future. As a training officer, you need to take personally the health of your officers; they are your responsibility.

Take Your Time

Progression is a vital part of law enforcement officer training. The appropriate amount of time needs to be allotted at each phase of the training so that officers can progress, gaining strength, speed, and endurance. The body needs time to strengthen and adapt to the stressors that are applied. If no time is allotted to strengthen and adapt before moving on to heavier stressors, injuries occur.

A basic example of progression would be, in a six-month program, every two months there would be an increase in training intensity.

The concept of progression can also be conceptualized in terms of phases. For example, phase one may encompass the first two months of training and can be understood as the base training phase. This phase emphasizes technique, endurance, and strength.

Phase two can be characterized as the intermediate/medial phase and may also last for two months. Conditioning is a primary focus in this stage. Basic concepts and teachings from phase one are utilized, but stress is introduced in the form of weight and time constraints. For example, long runs will turn into sprints and external weight manipulation such as fireman carries, kettlebell work, and partner drags will build strength and efficiency onto good technique with minimal injury because of the slow progression.

Phase three is the "high functioning" stage lasting for two months and it is the completion of a six-month physical training progression. In the high functioning stage officers are ideally injury free and performing at their highest level on all tasks.

Use Common Sense

All law enforcement training must make sense in terms of when officers are asked to perform different exercises and types of exercises. An example of sensible programming is scheduling heavy load days separately from speed days. In addition, scheduling speed days at the beginning of the week while recruits are not depleted of their energy is an example of sensible programming.

Trainers should understand the concept of energy depletion and that high-energy workouts should be situated separately and at the beginning of the week from other less depleting workouts. Lastly, plan to train different muscle groups on different days. Muscle groups should not be subjected to continuous load without time for proper recovery.

The final take-away is that trainers have to maintain realistic expectations and understand that injuries and setbacks occur during a training program from time to time. The key is in the reduction of such injuries. Take a look at the participants in your program and notice the varying degrees of physical fitness and body morphologies. Maintain an appropriate standard, but remain flexible in the way that you attain benchmarks. Require consistent effort and substantial progress, but remember there is individuality in each officer's physical journey.

Your ability to provide the personal attention many of participants need is very limited and may require more time than allowed in a class environment. If possible, offer your time before or after scheduled training sessions for corrective exercise demonstration to assist officers.

Understand that training in a group or team setting can be a challenge. Take heed of the famous concept of K.I.S.S. (Keep It Simple, Stupid). I have no idea who thought of this beautiful phrase but I've found that following it makes training much easier and successful. Sound and realistic planning in the beginning, along with recognizing your limitations with the group, will keep you progressing in the right direction.

The concepts described here are in no way an exhaustive list of the qualities a good fitness program encompasses, but applying them will aid you in reclaiming broken programs and enhancing well-functioning ones. An output-focused perspective places blame on the officer for their injuries when it is likely that the injury is a result of a training officer's inability to emphasize, demonstrate, and disseminate proper instruction. Integrating warm-up procedures, teaching proper technique, and implementing progression and sensible programming will reduce officer injury. In addition, staying educated in the field of strength and conditioning as well as maintaining realistic individual expectations can be the difference between being an average training officer and a master training officer.

We cannot prevent all injuries in law enforcement training programs, but we can certainly take steps to reduce them.

Darrell Burton has trained instructors from more than 100 law enforcement agencies across the country. He is a two-time recipient of the Law Enforcement Advisory Committee's Award for Instructional Excellence and recipient of the Basic Academy Outstanding Instructor Award. He is currently a training officer at the San Mateo County (CA) Probation Department and an academy instructor/training officer at the Academy South Bay Regional. He can be reached at thetrainingthatworks@gmail.com.