Texas' capital city of Austin was the site of the infamous Texas Tower sniper incident in 1966, widely credited with inspiring the creation of SWAT teams. Today it is home to a nationally recognized police crisis-negotiation team.

Texas' capital city of Austin was the site of the infamous Texas Tower sniper incident in 1966, widely credited with inspiring the creation of SWAT teams. Today it is home to a nationally recognized police crisis-negotiation team.

While crisis negotiators likely wouldn't have been able to halt Charles Joseph Whitman's deadly shooting rampage from atop the University of Texas clock tower, Austin Police Department's modern-day Critical Incident Negotiation Team has intervened in hundreds of potentially violent situations since its creation in the mid-1980s, saving the lives of citizens and officers.

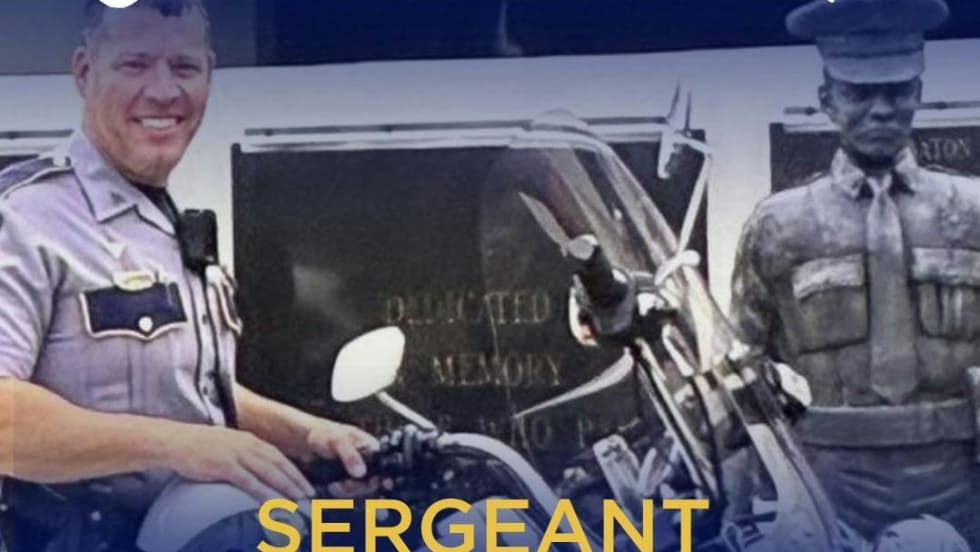

"We average between 20 and 30 call-outs in Austin a year," says Sgt. Rick Shirley, coordinator of the department's award-winning team. "We've had situations over the years where we have had to deal with suspects holding their spouses hostage, or their children hostage…. people who are suicidal or armed with a weapon, jumpers, barricaded subjects, and barricaded wanted felons."

Shirley estimates that he has worked between 400 and 500 incidents during his tenure on the 22-person negotiation team.

"In the 20 years the team has existed, we've had less than 10 persons who either killed themselves or required sniper intervention once negotiations started," says Shirley, a Texas native who has been with Austin Police Department since 1986.

A negotiator's job can be mentally and emotionally draining, but can also hold immediate rewards, notes Sgt. Wayne Vincent, a 22-year law enforcement veteran and crisis-negotiation team member since 1987.

"This is one of the few jobs in the police department where you can actually see the end result of your work," says the Kentucky native. "If you have done the best you can, most of the time you can resolve the situation without any further violence."

Police crisis negotiation in the United States has roots in the New York City Police Department. NYPD formed the nation's first hostage negotiation team following the high-profile Munich Massacre. The mishandled hostage-taking incident resulted in the murder of 11 Israeli athletes during the 1972 Summer Olympics in Munich, West Germany. In addition to numerous tactical and intelligence failings during the incident, German police had no special training in hostage negotiation.

In Austin, negotiation team members—all of whom participate as a secondary assignment in addition to regular duties—routinely coordinate their activities with those of the Special Weapons and Tactics team. The two groups respond together during virtually all crisis-negotiation call-outs.

In contrast to the military geared-up SWAT officers, negotiators dress in polo-style shirts and regular pants. Whenever possible, they speak directly to the subject in crisis, often over the phone.

"You demonstrate to the person that you're not just there to do a job, that you have an actual interest in what they say," Shirley says. "In many cases, you may be the first person that he feels is listening to him and is hearing what he has to say. Most people are trying to tell him what to do."

Vincent says that building trust starts with "baby steps," such as delivering on promises to provide soda, cigarettes, or food to barricaded subjects. In one particular case, a male suspect—whom Vincent had negotiated with during a previous barricaded incident—specifically requested him via cell phone during a high-speed pursuit along Interstate 35.

"Eventually, it becomes you and him working to resolve the troubles," Vincent says. "Sometimes, even though the subjects are anti-police, they begin to think of you as someone helping to solve the problem. They'll think of SWAT as the police."

Last year, the Austin Police Department Critical Incident Negotiation Team was recognized for excellence at the national level, winning first place among 24 teams from across the nation in the 16th annual Hostage Negotiation Training and Team Competition. In 1993, the Federal Bureau of Investigation asked Austin negotiators to join the FBI crisis-negotiation team during the 51-day standoff at the Branch Davidian compound in Waco, Texas.

A successful police negotiator must be able to think on his or her feet, and adapt to changing, often lengthy crisis situations. Once a negotiator establishes rapport with a subject, commanders try to keep him or her on scene as long as possible. But as the day (and sometimes night) wears on, other team members must take up the negotiation reins.

"We're looking for someone with a personality type that works well in a team concept, and has the demeanor to step out of the cop role, and into a less confrontational role," says Shirley. "Law enforcement officers in general are used to trying to take control of things, and get things resolved, and move onto the next thing. (Among some policing professionals) it's perceived that if someone wants to kill himself and place himself in harm's way, that should be the natural evolution of the incident."

To be effective, a negotiation team must have the backing of the agency administration, Vincent and Shirley both emphasize.

"You want to make sure you have the support of the highest members of the department," Shirley says. "Historically, negotiators were not perceived in the most positive way by the rank and file. Negotiators were seen as a waste of time. In many cases, that is still true."

But negotiators are police officers first and foremost, Vincent stresses.

"We don't consider a situation a negotiation if violence is still in progress," he notes. "If it's ongoing, it's a tactical situation. We're going to be armed, negotiate from cover, and only do it if the SWAT commander deems it can be done safely."

"Just because we are negotiators, it doesn't mean that the crime goes away," Shirley adds. "We're committed to making everyone safe."

Bryn Bailer, a former newspaper reporter, is a contributing editor for POLICE. By night, she is a member of the Tucson (Ariz.) Police Department Communications Division.