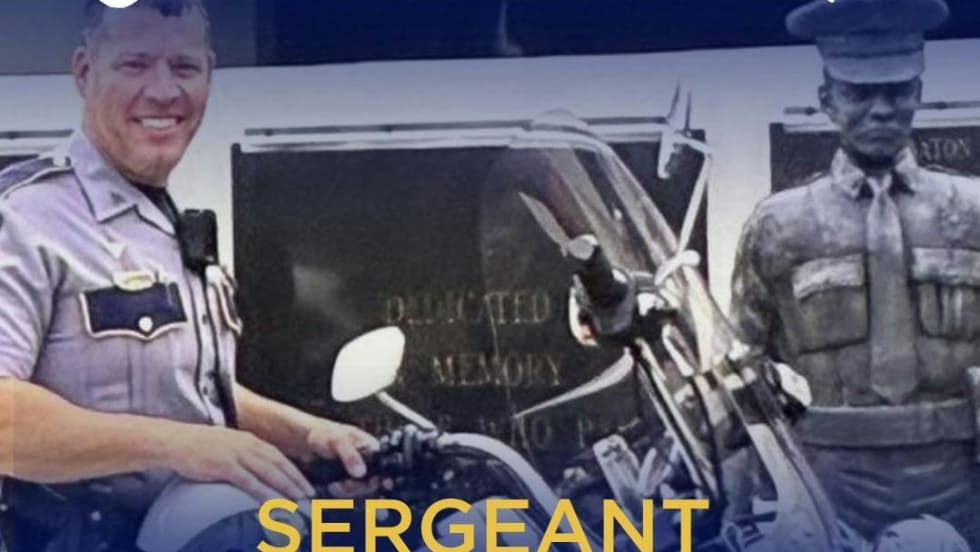

It was two days before Christmas 2004, and Sgt. Randy Wills of the Pueblo (Colo.) Police Department was a case study in sleep deprivation. It had been a busy holiday season with very little peace on earth and even less good will toward men. Wills needed rest.

It was two days before Christmas 2004, and Sgt. Randy Wills of the Pueblo (Colo.) Police Department was a case study in sleep deprivation. It had been a busy holiday season with very little peace on earth and even less good will toward men. Wills needed rest.

All he wanted to do was take some time off and spend some quality hours with the family. But when the phone rang, and the brass on the other end wanted him to work overtime, Wills answered the call.

Wills supervised the relief team, meaning that he and his officers covered the north and south patrol areas during graveyard shift when either of the regular teams was off. This night they would be covering the south end.

The Pueblo PD has 195 sworn personnel who serve a population of 125,000. It's by no means Mayberry. But some nights it's as quiet as a sleepy little burg, especially in the winter.

As Dec. 23 rolled over into Dec. 24, anybody in Pueblo who wasn't working and had any sense was in a warm bed. Winter had come to the southern Rockies with an icy blast of 20-below-zero weather. It was nasty outside.

But for the cops on the relief crew, the brutal cold had its good side. For the most part, they could stay in their warm cars, and the bad guys didn't want to come out and freeze. The cold and the fact that Christmas was just days away made for an agreeably quiet shift.

Still, something nagged at Wills. He'd left his AR-15 secured at his father's house. He kept thinking about going back for it, but the peaceful night made it easy for him to rationalize that he didn't need the rifle. Don't worry about it. Nothing's happened. Nothing's going to happen, he thought.

Normally, Wills wouldn't have dwelled on not having a piece of equipment. He would have either gone to get it or forgotten about it. This night, Wills couldn't get the rifle out of his mind. He finally decided to drive by his father's house and pick it up.

Wills felt a little silly about picking up the rifle so far into his shift, and at such a late hour. But the sense of relief he felt about having his patrol rifle would soon become profound.

Pitt Maneuver

As Wills backed out of his driveway, a call came over the radio. A car-to-car felony menacing with a gun had taken place only three blocks away. Wills copied the suspect vehicle's description, then put his patrol car in drive and accelerated. It didn't take long for him to find what he was looking for: A white Chevrolet Camaro T-top filled with suspected gang members, traveling just ahead of him.

Wills coordinated units to his vicinity, as the Camaro suddenly turned into a parking lot and headed toward an alley behind a grocery store. A Pueblo officer tried to block the Camaro in the alley with his patrol car. The Camaro kept coming, rammed into the patrol car, and sped away.

It was time to end this, Wills thought. He gunned the engine of his patrol car and aimed it at the Camaro as it passed in front of his grill.

Wills' road position was less than optimal, but the timing of his Pitt maneuver was good. The front end of his patrol car struck the driver's side of the Camaro, sending both vehicles into simultaneous spins. The Camaro collided with a curb where it came to rest with the front end of the patrol car barricading the driver's side door.

Immediately, there was a flurry of activity. A male suspect leapt from the opposite door of the Camaro. Wills grabbed his AR-15 as he jumped out of the pasenger door of his patrol car. Inside the Camaro, a second male suspect climbed from the driver's seat to the passenger seat.

Wills leveled the AR-15 rifle on the Camaro's occupants as he stepped toward the front of the aging Chevrolet muscle car. The Camaro's driver, identified by police as Daniel Pino, 17, continued his movement across the front seat. Wills yelled for Pino to freeze. Pino's eyes locked on Wills for a split second. Then, Pino, with one foot already out of the passenger's door, suddenly abandoned his intended flight and reached back and down toward the center console area.

"Show me your hands!" Wills demanded.

He got compliance. Pino turned back toward Wills, and Wills saw his hands. But police reports and Pueblo County investigators say that as Pino's right hand passed the visual plane of the dashboard, Wills saw a revolver. And its barrel was swinging toward him.

Wills commanded Pino to drop the pistol. Reports and eyewitnesses say Pino did not respond. He held the pistol, bringing it around to where the barrel threatened Wills. Wills fired a single round from his AR-15 through the Camaro's windshield.

It caught Pino center mass, propelling him back against the seat rest. For the last time, Pino's eyes met the officer's and seemed to convey an acknowledged mortality: You killed me.

Seeing that Pino was no longer a threat, Wills turned his attention to the other men in the Camaro's back seat. "Don't move! Keep your hands where I can see them!" He barked.

From the back seat came a scared cry, "Don't shoot, Wills." Someone in the car not only recognized Wills, but had the good sense not to challenge him.

Wills keyed his portable radio and advised dispatch that he had been involved in a shooting and requested paramedics. He then moved to the open passenger door and pulled the suspect through it to the ground, face down, and searched him. He remembers telling Pino to hang on and that paramedics were responding. But if the mortally wounded teenager heard him, there was no sign of it.

Is There a Gun?

Once the suspects were in custody and the scene was secured, Wills shifted his focus from physical survival to administrative survival. He glanced through the open passenger door and momentarily panicked. He couldn't see the suspect's gun. Another officer on the scene shined his flashlight on the passenger floorboard. "There it is, Randy!"

Wills stared at the gun. It was a 9mm Smith & Wesson revolver. Ironically, the presence of the weapon, which seconds before had been a threat to his existence, now offered Wills a strange sense of relief.

"I had just gone through an administrative investigation behind a Taser incident, and I was stressing after the shooting," Wills says. "I knew that it was a clean shooting, but I was worried about how others in the department would view it, as well as politicians, community activists, and the news media."

Bad Christmas

Wills didn't have to wait long for the local media to chime in on the incident. The Christmas morning edition of the Pueblo Chieftain had this banner headline on the front page: "Pueblo Police Shoot, Kill Teenager."

"That headline hit below the belt," says Wills. "It nagged at me. I found myself second-guessing my actions: Was he turning toward me with the gun? Or was he trying to turn away from me to stash the gun?"

Wills was battered by conflicting emotions and second-guessing. During the incident, he felt on top of his game. All of the hours he had spent in training, on the range, and at competition meets had paid off. As Wills had explained to investigators, he'd fired only one round because that's all he needed to end the threat. But now he wasn't so sure. When he'd fired that round, had his mind colored the situation with elements that weren't there? Or was he doing it now?

All of Wills' questions, all of his doubts, and the stress of taking a life in the line of duty began to affect his personality. "I was becoming more sarcastic," Wills says. "My attitude was, 'Just don't bother me with petty BS.' I found myself having arguments with my wife. I would go to SWAT training and watch videos on chest entry wounds and feel my blood pressure start to go up. When it came to working the field, I found myself concerned and wondering what would happen if I were to suddenly get involved in another shooting."

On Dec. 31, Wills received the call from Pueblo PD Chief Jim Billings: The Pueblo County District Attorney's Office had found the shooting justified.

Wills was back on duty. Still, he found himself displaying less initiative in the street. He doubted himself, and he wondered if he had remembered the incident exactly as it happened.

A few weeks later, a conversation with a Pueblo County medical examiner chased away much of Wills' doubt. She described to him how the trajectory of his rifle round through Pino's upper heart could only have been inflicted in the manner in which he had described.

Mandatory department appointments with the psychologist also helped Wills cope with his feelings about the shooting, but they didn't prevent the occasional bump in the road. In his mind's eye, he continually relived the moment of the shooting, especially Pino's eyes.

Wills doesn't know if Pino recognized him in that second when the youth's eyes met his, but he realized soon enough that their paths had crossed years before, most notably when Pino was a child and defiantly flashing "trece" signs with his fingers in a picture taken by the child's proud uncle.

Wills had been working in the gang unit at the time, and he asked Pino why he would do such a thing. The then nine-year-old boy had the lingo down pat. "I'm down for life," he had said to Wills. Disgusted, Wills tried to warn him. "Man, you're going to end up dead in the gutter."

Unfortunately for both Pino and Wills, that young gang officer's prediction came true.

Dean Scoville is a patrol supervisor with the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department and a contributing editor to Police.