Gonzalez glanced back in Anderson's direction a second time. "Aw, shit!" he said, his facial expression leaving no doubt as to the sincerity of the sentiment. And with that, he tossed his soda on the ground and took off running around the corner and southbound on Adams Street.

Within the confines and context of Glendale, Calif., Chevy Chase is a major thoroughfare that bisects the city with two lanes in both directions. On that thoroughfare, 9:30 p.m. can prove a busy time. On Monday March 31, 2008, it would prove unusually so.

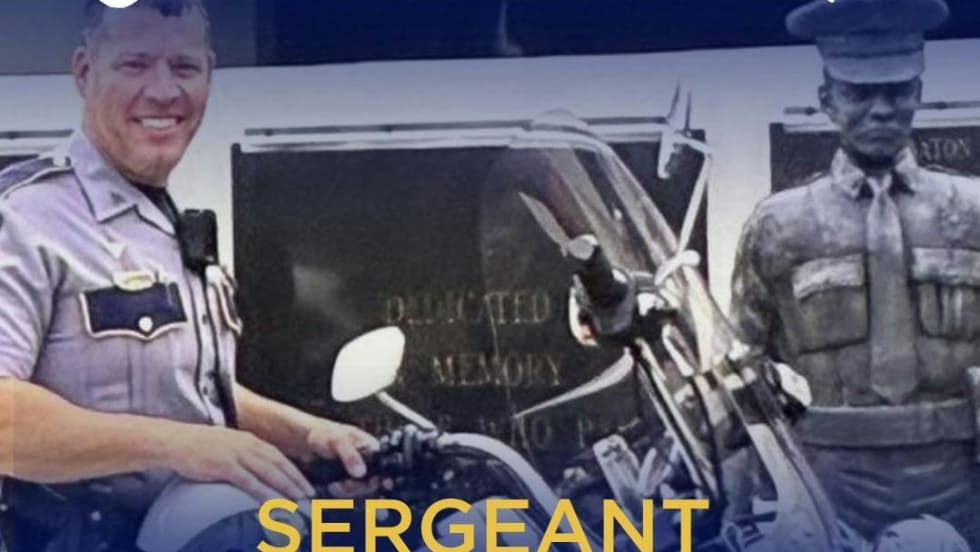

The catalyst for that action was a happenstance observation made a block away near the intersection of Colorado Boulevard and Adams Street. That was where Sgt. Todd Anderson, working the Glendale Police Department's Special Enforcement Detail, was driving westbound. With 20 years on the job—eight on the detail alone—Anderson had been around this block and others many times. His experience made his eyes naturally gravitate toward a heavily tattooed male Hispanic walking westbound on the south sidewalk drinking a soda.

The two men's eyes locked with one another. The man on the sidewalk may not have been wearing prison blues; Anderson's ride might not have been a marked patrol vehicle, and yet each man immediately recognized the implications they had for one another and where their respective allegiances lay within the criminal justice system.

For his part, Anderson was content to maintain his patrol speed and roll past the man with the bushy mustache, so as to allow him to entertain the momentary illusion that all remained well in his universe. As he did, Anderson was conscious of his own posture: Head facing straight ahead, neck taught, eyes darting toward his review mirror in a bid to keep track of the pedestrian's progress.

Two Weeks Out

The pedestrian in question was Daniel "Danny Boy" Gonzalez. Only two weeks out of prison, Gonzalez had just two hours before murdered a fellow gang member three-and-a-half miles away in LAPD's jurisdiction, police say. Like the sergeant, Gonzalez could well have used a mirror himself just then. But being deprived of one and unable to suppress the temptation, he indulged himself a protective glance over his right shoulder at the unmarked Crown Vic. Satisfied with its westward progress, Gonzalez maintained his pace.

With Gonzalez's head turned back away from him, Anderson quickly executed a U-turn and curbed the car along the south sidewalk, coming to rest about 10 feet behind the man.

"Hey," Anderson called as he stepped from his ride.

Gonzalez glanced back in Anderson's direction a second time. "Aw, shit!" he said, his facial expression leaving no doubt as to the sincerity of the sentiment. And with that, he tossed his soda on the ground and took off running around the corner and southbound on Adams Street.

Anderson threw his car door shut and initiated a foot pursuit after Gonzalez, who sprinted toward the intersection of Colorado and Adams where he hung a left. As he raced after the man southbound on Adams, Anderson could see his quarry working his waistband.

Anderson had been here before, chasing some bozo laboring under the impression that he might somehow magically discard his dope without Anderson either catching sight of the contraband or getting his hands on him.

Be Careful, Officer!

But tonight was different and the only thing the man tossed was the barrel of a gun over his shoulder at the pursuing sergeant. A bright flash of amber split the darkness and a loud boom echoed down the street.

"Be careful, officer!"

The words were those of a passing motorist, who repeated them not once, but twice. The advice was heartfelt, but redundant as Anderson had already come to a similar conclusion. Pulling the reins on himself just enough to keep an eye on his assailant, Anderson began coordinating units to his location via his portable radio.

Further down the street near the intersection of Elk and Adams, Gonzalez disappeared from view. Anderson's gut told him that the suspect had probably hunkered down in a yard located at the northeast corner of the intersection. Its grounds lent themselves to such enterprise and anything similarly accommodating was seemingly too out of range to have been gained in so short a time.

In the Bushes

Within 30 seconds, additional officers were already on scene and half of a perimeter had already been established. As the officers were deploying, a woman walking her dog made her presence known to one.

"Officer, I don't know what you're looking for, but some guy just backed into those bushes over there," she said, indicating a residence—some 280 yards from where Anderson had last seen the suspect.

This information was relayed over the radio. Listening to it, Anderson found himself in deliberation. To his mind, there was no way that the suspect could've covered that distance in so short a time. Still, stranger things had happened and when it came to officer safety, it was better to be prudent than sorry. He bit his tongue at articulating his intuitions lest the officers in the vicinity drop their guard. He was thankful he did.

As officers began approaching the vicinity of the bushes, the suspect suddenly jumped out and started shooting at them gangster-style. Despite the cinematic cant of the gun and lack of any sight alignment, the suspect was able to get off a miraculous shot: One of Andersen's fellow officers, Robert William, was struck in the chest.

And with that, the suspect was once again mobile, darting through yards and running an additional hundred yards north on Chevy Chase. That was where an intercepting Sgt. Mike Toledo pulled his patrol unit into a driveway and cut him off. Backing up a driveway, Gonzalez retreated to a front porch where he resumed his gunfire at the officers.

Rounds tore into not only Toledo's car door, but that of a motorist making a left turn from Colorado onto Chevy Chase. Exiting his car, Toledo took cover behind it even as more officers pulled up at the location and fanned out in a semi-circle formation behind cars and trees so as to minimize any potential for crossfire.

Toledo and Officer Charlton Vidal were under fire but they gave as good as they got, with Toledo firing through the window of his car with his sidearm and Vidal squaring off against the parolee with a short-barreled Remington 870 shotgun.

Several rounds struck Gonzalez in the upper torso and he dropped his weapon before plummeting into the driveway near Toledo's patrol vehicle. Despite commands for him to remain still, Gonzalez's hand reached for the fallen handgun. More rounds were fired. And Gonzalez's hand moved no more.

30 Hits

Anderson puts a conservative estimate of the number of detention-based contacts he'd made prior to the shooting at 10,000. Throughout, he'd encountered varying degrees of cooperation and everything from a lack of compliance to outright resistance. But those latter responses had to some degree conditioned him so that while he was always aware of the potential of a suspect to pull a gun on him, when the reality asserted itself it was as though the felon had deviated from a well-rehearsed script. Whatever else, the sergeant reacted to the threat quickly and prudently.

"Foot pursuits were not new to me, but the single fluid motion leading to the shooting was new," Anderson reflects. "I knew it was a big gun because it was as loud as can be and I saw a lot of flash come out. I was confident it wasn't a .22 or anything lightweight."

As it was, police say the round was a .45 fired from the same handgun that Gonzalez had two hours before pulled out during a fight and used to kill a friend, Jose Garcia.

Hearing the suspect's shot actually provided a measure of comfort to Anderson.

"I'd been present at other shootings and my frame of mind has always been if you hear the gunfire and you're on your feet, you're OK. That was what my mindset was on this night: If I can hear the round, then I survived it.

"Video surveillance showed that when I got shot at, there was a parked car at the curb to my right and a wall to my left so there was not a lot of room," Anderson adds. "When he shot, I immediately turned around, almost like I was running back to the police car, but in reality, I ran around the car and out into the street to get distance and better situational awareness. I tried to get a visual of the whole block to see what was going on and to make a safer approach of the yard where I thought he was."

Officer Robert William proved no less lucky than Anderson. The round fired by Gonzalez struck him in his protective vest. He hadn't even realized that he'd been struck until after the incident had concluded, and he felt pain associated with the round's blunt force trauma.

Gonzalez fared less well. He was shot more than 30 times: Multiple wounds to the face, chest, left leg, abdomen, back, and external extremities.

Anderson said that nobody deviated from tactical protocol or went off half-cocked throughout the operation. Although tempted to respond at the time of the second engagement, he knew that it could prove tactically compromising. "I was back at Adams and Elk where I thought he would be. When I heard them engage the suspect, I thought he might run back, so I maintained a perimeter on this side," he says.

Anderson notes that a broad range of experience was on hand that night, from guys who had 30 years on the job, to rookie Brian Young who'd been on training only as long as Gonzalez had been on parole and was nonetheless actively engaged in the firefight. Anderson is extremely proud at the way Glendale's finest conducted themselves that night. He notes that despite the fluidity of the event no one lost their composure and the highest level of officer discipline was maintained. Moreover, officers didn't have to be told what to do either before or after the incident, either taking the initiative or accepting operational positions—e.g., perimeter, searching, evacuating—as they became evident.

Looking back, Anderson recognizes a couple of things in hindsight.

"The first was that the suspect was wearing a short sleeve shirt, black pants, and brand new white tennis shoes," Anderson says. "Between his having his prison buff on and his sleeved tattoos, I just instantly recognized that he was on parole. The second thing was less an epiphany than a reminder: That a determined and conditioned man can cover a hell of a lot of ground. Not only did he cover the distance of roughly three football fields throughout this thing but he was still trying to run when cornered and trying to engage the officers after he'd already been shot."

Knowing parolees and how they practice for such engagements much as officers do, Anderson was not so much surprised at Gonzalez's survival mindset as intrigued by it. Just what was it that drove Gonzalez to fight with such determined ferocity despite odds that were in evidence against him? A tox screen revealed marijuana, and a blood alcohol of .02. No cocaine. No PCP. No meth.

Might it have been sheer hatred? It wouldn't have been the first time that a bad guy demonstrated such rage toward officers, and given the fact that the man had spent most of his adult life in prison and had no family members to speak of, it makes for a reasonable supposition.

No less of a mystery is why the man happened to be in Anderson's patrol area at that hour.

"We don't know why he came to Glendale," says Anderson. "He had $1 in his pocket. He had a sock full of extra rounds in his pocket. He shot 8 or 9 rounds total. One of our guys had even struck his gun with a round, as its magazine was bent."

For their heroic actions that night, Officers Charlton Vidal and Sgt. Mike Toledo each received the Department's Medal of Valor. Officer Robert William was recognized with the agency's Purple Heart.

Sgt. Todd Anderson received the Chief's Award of Excellence. He has since been promoted to lieutenant and now supervises patrol.