The questions many in the SWAT community are asking is what can SWAT-trained officers do to help protect fellow officers during demonstrations and other incidents and how this might affect the way SWAT teams operate in the future.

The concept of fielding highly trained teams capable of executing extremely dangerous missions with weapons not available to patrol officers grew out of the 1960s and a number of sniper attacks.

When Charles Whitman opened up on the public from a tower on the campus of the University of Texas in 1966, local law enforcement was not trained or equipped to handle that situation. Those Texas officers heroically ended Whitman's attack. But the Texas tower shooting opened a lot of eyes in law enforcement and had many officers wondering: "What if it happened here?"

That question of what if we have to face a barricaded gunman with a rifle was one of the driving forces behind the development of tactical law enforcement units. Another driving force for the spread of the SWAT concept was the riots of the late 1960s and early 1970s when snipers fired on officers and other first responders during what we can probably now call America's first war on police.

The second war on American police is currently under way, as a disturbing number of officers are being killed from ambush by attackers who see nothing but their uniforms and/or badges. This is bringing back some unpleasant memories for officers who were on the job for the riots and cop killings of nearly 50 years ago.

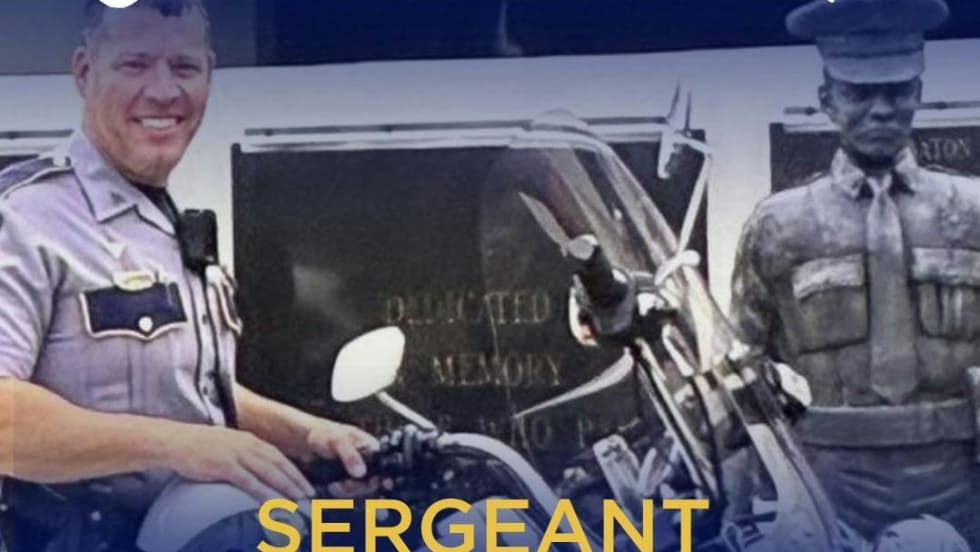

"The 1960s up into the mid-1970s was a riot/sniper era," says retired Cleveland SWAT sergeant Robert O'Brien. "We've seen it before. When you get criminal snipers who have some training and some knowledge they are very dangerous."

The questions many in the SWAT community are asking is what can SWAT-trained officers do to help protect fellow officers during demonstrations and other incidents and how this might affect the way SWAT teams operate in the future.

Given that the very idea of special weapons and tactics teams was conceived to offer additional protection for the public and first responders, including fellow officers, it's not clear how the missions of SWAT may evolve based on recent attacks on officers and the public or whether they even need to.

Crowd Control

Leading voices in the tactical law enforcement community say they do not want to see SWAT units play a greater role in actual crowd control operations.

Major Ed Allen of the Seminole County (FL) Sheriff's Office says SWAT officers should not be tasked to crowd control missions that are better performed by mobile field force teams.

Allen, who helped draft the "The Tactical Response and Operations Standard for Law Enforcement Agencies" issued in 2015 by the National Tactical Officers Association, says SWAT has a role to play in policing civil disturbance situations, but it should not be hands-on with demonstrators unless needed.

Allen says NTOA definitely believes SWAT should be ready to respond during civil disturbances but only if SWAT capabilities are needed. "If there is some type of victim rescue or officer rescue needed in the middle of a civil disturbance or protest, then there is absolutely a role for a SWAT team to play," he explains.

The problem, according to Allen and other members of the tactical officer community, is that some law enforcement executives use their SWAT teams as a hammer for every nail. Larger agencies likely have specialized teams with specific missions such as crowd control (mobile field force) and barricaded suspects (SWAT). But smaller agencies may only have enough resources for a tactical unit because they don't anticipate the need for a crowd control unit. "We (NTOA) want agencies to make the distinction between the two different types of teams. Otherwise, SWAT teams get put in a difficult position of helping manage civil disturbance when that is not what they were intended to do," Allen says, explaining that equipment, tactics, and training are very different between mobile field force teams and SWAT.

High Ground

NTOA and other experts say the best deployment for SWAT during situations like the Dallas protest is in reserve, waiting to respond as needed.

But another role that SWAT can play and will likely play more often in the near future is overwatch or what members of the tactical community call "high ground." The idea is to place spotters and even snipers in buildings along the protest route to spot people who may present threats and direct officers in to check them out or respond to attacks.

One of the most asked questions following the Dallas sniper attacks of July 7 was did the Dallas Police have overwatch in place. It's likely we won't know the answer to that question until the after-action report is released.

And even if Dallas SWAT had high ground positions on the night of July 7, it likely wouldn't have made a difference. Experts say areas like downtown Dallas with its many tall buildings and wide straight roadways create an "urban canyon" and a complicated environment for locating and neutralizing a sniper. Worse, unlike carefully choreographed parade routes for dignitaries, where high ground is standard operating procedure, protest demonstrations often don't follow the pre-planned route so overwatch can quickly be rendered useless.

Which is exactly what happened the night of July 7. It's been reported that the protesters marched away from the planned demonstration site. So if officers in high ground positions were covering that site, they lost effectiveness the minute officers and protesters left it.

And once the sniper's location was pinpointed, Dallas SWAT was quick to respond. The team fought with the gunman inside an El Centro Community College building, effectively pinning him and preventing him from escaping and murdering more officers.

Planning and Tactics

One of the most important roles SWAT can play in helping an agency deal with a crowd control situation is in the planning of response and analysis of how to thwart potential threats.

Members of the tactical community say it's important for SWAT to have a role in the planning of not just the agency's response to the proposed event but also what will happen if things go wrong. A key aspect of planning is when and how SWAT will respond. Even more important is a detailed threat analysis that might identify a potential vulnerability and allow the agency to shore it up.

O'Brien says he believes people in and out of law enforcement often forget the importance of the "T" in the SWAT acronym. "If you have good, sound, proven and effective tactics, a detailed plan, and enough trained and equipped officers to do the job, then sometimes good things happen."

Another key factor in planning for and responding to mass events is multi-agency cooperation. "A single agency can't do this alone," says Allen. "No matter how large the agency, when we have significant events like this, there is a large impact on an agency's operations."

Allen adds that the time for agencies to establish mutual aid is not during a major incident but well before. "We know from post-incident analysis in the past that multi-jurisdictional response always goes better when there is a pre-established relationship and response plan between those agencies. Both during and after the incident we have to maintain good partnerships with surrounding organizations."

SWAT Response

The last three major critical incidents in the United States, the Pulse nightclub massacre in Orlando, the Dallas sniper attack, and the Baton Rouge ambush, all show how the relationship between SWAT and first responders is flexible and evolving.

It used to be said that when civilians need help they call the police, and when police need help they call SWAT. Though it's unlikely that many first responders were ever totally in agreement with that sentiment.

But since the 1997 North Hollywood Bank Robbery, it's become common for first responders to have rifles and other tools that were once restricted by many agencies to SWAT use.

Not only are first responders better equipped now than they were in the past, they are also better trained, and expected to take action and not wait for SWAT, especially in active shooter situations. "Today's patrol officers are often as well equipped and trained as the SWAT officers of the past," says Allen.

Those first responding officers may also be former or current members of SWAT teams. Very few agencies have the resources or the cause to make SWAT missions and training a full-time job for the members of their tactical teams, which means members of the teams are among first responders.

Having officers with SWAT training working patrol is a very effective way to get SWAT assets on scene in a hurry, and it can save lives. When officers and deputies responded to the ambush that claimed three officers' lives in Baton Rouge, among them was at least one SWAT-trained officer who took out the shooter. The unidentified officer is credited with ending the cop killer's attack by shooting him with a rifle—even though the officer did not have an unobstructed view of the gunman—from 100 yards away.

In Orlando, the gunman was first confronted by an off-duty uniformed officer who was working security at the Pulse nightclub. Armed with only a pistol, he was forced to withdraw and call for help. Six officers answered that call and engaged in a sharp 10-minute firefight with the gunman. Many of the officers in that fight had SWAT training. Unfortunately, they were unable to prevent the terrorist from taking refuge in a restroom where many of the club's patrons and staff had taken refuge and a hostage situation ensued. Those officers also did not have rifle-rated armor, so they were relieved by the arriving active SWAT team.

The point here is that the concept of first responders calling in SWAT is becoming something of an anachronism, as many first responders themselves are trained, equipped, and expected to take action against active shooters and are willing to do so.

Moving Forward

It's likely that after Dallas SWAT units will be called upon to perform more high ground operations during protest marches. That will require much more advanced planning for scheduled demonstrations and probably more multi-agency cooperation to ensure there are enough tactical officers available to provide both overwatch and ground response should something go sideways.

Another thing that is likely to happen is that law enforcement executives will worry less about how armored rescue vehicles appear too military for law enforcement operations, at least for a few months. In both Orlando and in last year's Colorado Springs Planned Parenthood attack, a Lenco Bearcat armored rescue vehicle was used to breach the buildings and give officers the opportunity to take the suspect into custody or kill him. Either way, the Bearcats were essential in ending the violence.

Ending the violence was also the goal of a controversial tactic used to kill the Dallas sniper. With negotiations going nowhere, as the gunman taunted, sang, and threatened Dallas officers, Dallas SWAT officers came up with the idea of taking the sniper out with a robot-delivered bomb rather than risk more officer casualties. Dallas Police Chief David Brown authorized the tactic, and the gunman was killed by one pound of C-4 explosive.

The tactic was controversial, but it achieved the primary mission of SWAT since the conception of special weapons and tactics units. It saved officers from being wounded or killed and it protected the city of Dallas from a man who had not only firearms but threatened the police that he had explosives. Indeed in his home he had the makings for explosives.

Chief Brown has no time for people who question the decision. "This wasn't an ethical dilemma," he told the press. "I'd do it again to save our officers."

Brown's strong stand against activists who decry "killer robots" is important because in an era when police are being stalked and murdered and civilians are being slaughtered in places of entertainment by terrorists, SWAT tactics and techniques will have to evolve. And that may very well mean more teams will have to find innovative ways to rescue people, including fellow officers, and those methods may also be controversial. Which means law enforcement executives—like Brown—will have to have strong backbones and back their troops.