How Puppies Behind Bars is transforming the lives of inmates, officers and community members by training facility dogs.

In the bustling halls of the Tuckahoe (New York) Police Department, there’s a new kind of officer on patrol—one who’s less concerned with the badge he wears and more with the wag of his tail.

Meet Eddie, a nearly two-year-old yellow Labrador, whose mission is as heartwarming as it is vital: to promote wellness within the department, assist victims of trauma, and foster connections with the community.

With a gentle temperament and a coat that practically begs for belly rubs, Eddie may not have a traditional set of police tools, but what he brings to the force is no less impactful.

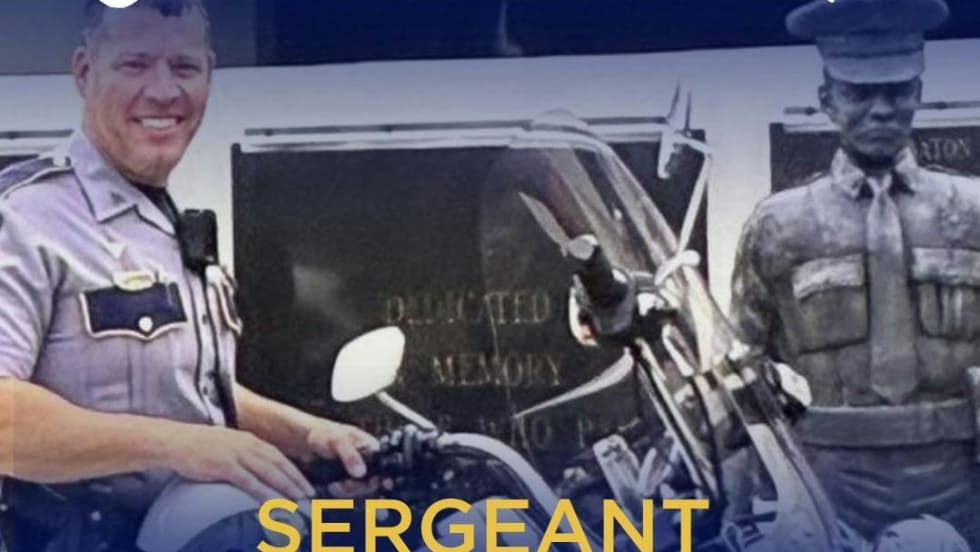

Since being paired with Chief Larry Rotta in August, Eddie’s role has already proven invaluable, especially when it comes to helping young victims process and share painful experiences.

Take the case of a seven-year-old girl, a victim of a heinous crime, who found comfort in Eddie’s calming presence as she sat through hours of testimony.

“Usually, children don’t go through with describing sexual crimes because parents don’t want them to relive the trauma,” Chief Rotta explains. “But Eddie sat with the child for the entire day, providing a sense of security as she bravely rehashed one of the most horrific things I’ve ever heard in my career.”

For the officers and public in Tuckahoe, Eddie isn’t just a therapy dog—he’s a lifeline.

Puppies Behind Bars Serves a Need

Eddie isn’t just any service dog—he’s a product of an impactful program called Puppies Behind Bars. This nonprofit organization, founded by Gloria Gilbert Stoga, has an innovative mission: to train prison inmates to raise puppies that will eventually become service dogs for veterans, first responders, and law enforcement.

Through the program, puppies like Eddie live with their "puppy raisers,” inmates who are trained to teach the dogs essential commands, routines, and socialization skills. Over the course of about two years, the dogs grow up within correctional facilities, forming deep bonds with their trainers as they master behaviors that will help them in their future roles as service animals.

Eddie’s path to the Tuckahoe PD began in just such an environment, where he was carefully nurtured and trained. Thanks to Puppies Behind Bars, Eddie wasn’t just prepared to be a loyal companion, he was set to make a real difference in officers’ and community members’ lives.

Stoga started the program to raise guide dogs for the blind. In 2006, the organization’s mission shifted to bomb-sniffing dogs and service dogs for veterans. But in 2019, the nonprofit paired its first dog with a police officer, not for patrol but for officer wellness and community policing.

Stoga highlights the growing need for officer wellness programs as the reason for the shift. Chief Rotta agrees, explaining that officers witness terrible things daily.

“Officers can witness a traumatic event but are expected to write a report and move on to the next call. But that is not normal,” he says. “It’s not human to just push things aside and get back to work.”

Adding a facility dog boosts officer wellness, Rotta adds. He shares putting a dog in a room with an officer after a traumatic event for a half hour can bring down their stress level. Dogs can sense people’s stress, he says, and will sit with struggling officers and love them without judgement.

“Officer wellness is a critical reason for having these dogs,” Stoga admits. “Police officers who are going through on-the-job stress or personal stress may hesitate to talk to a coworker, trained therapist or wellness officer, but they will talk to the dog. They will say things to the dog that they would never say to a person. So, the dog becomes the conduit to which the other person in the room can follow up and say, ‘Here are some things that might help.’ We see this all the time. Cops will tell the dogs things they will not say to other police officers.”

On days where trauma hasn’t been part of the job, Rotta says dogs like Eddie lighten the mood of the entire department.

“I don’t know how to explain it but having a dog in the department restores normalcy,” he says. “It’s priceless.”

Breaking Down Barriers

Facility dogs can also double as community policing dogs, breaking down barriers between police and the community, according to Stoga.

“When a police officer walks down the street with a labrador retriever at his side, the dog becomes a conduit to conversation,” she says. “The community member sees the officer as a person with a lovable dog. It immediately breaks down barriers.”

Rotta says one of Eddie’s primary uses is community policing, where he visits senior centers, schools, daycares and more.

“He really breaks down barriers with young people. Many kids today are pre-programmed to hate police,” he says. “But with the dog, I can walk up to teenagers and talk to them, and they won’t be suspicious about why a police officer is talking to them.”

In fact, Rotta says Eddie has quickly gathered a following in the community. People know him, follow what he’s doing, and care about him.

Puppies Training Behind Bars

Dogs in the Puppies Behind Bars program undergo a unique blend of basic training and commands that help keep them mentally sharp and engaged.

"They learn basic obedience, but we also teach them commands like saluting, playing peekaboo, shaking paws, giving high fives, and even posing for photos," explains Stoga. "The training isn't the same as a bomb or patrol dog’s, and we incorporate commands throughout the day to keep them fluid and prevent them from forgetting what they’ve learned."

The training process begins when puppies enter the prison at just eight weeks old. Puppies Behind Bars breeds about 80% of their dogs and purchases the remaining 20%.

Once they arrive, the dogs are paired with carefully selected incarcerated individuals who are eligible to participate in the program. These trainers—who must have clean prison records, and no crimes involving police officers or sexual offenses, live alongside the dogs for up to two years, teaching them skills that help them succeed as service animals.

"We work in maximum and medium-security prisons because it takes about two years to properly train a dog, and inmates need to be in the program for at least eight months before they’re matched with a puppy," Stoga says. "The training we invest in the incarcerated individuals is just as important as the training we invest in the dogs. We need to ensure they are committed and capable of raising dog after dog, which is why the length of their sentence plays a role in their eligibility."

The inmates are paired with a professional trainer who goes into the prison one full day a week, 52 weeks a year, to oversee the training process.

Socialization is a key part of every K9s training, Stoga adds. She explains the dogs go everywhere with their inmate, be it a job site, church or synagogue, or the library.

“The only place they cannot go is the mess hall or infirmary,” she says. “The dogs are with them throughout the day and live in their cells, unless they are out with volunteers.”

A cadre of volunteers makes sure the dogs are exposed to the outside world. The volunteers receive a profile on what the dog is working on. For example, the profile might say the dog needs more exposure to children. The volunteer would then take the K9 on an outing to a school or daycare. Another dog’s profile might show they need help working in a car, so they are paired with a volunteer willing to help with that.

“Our dogs ride on buses, in taxis, go to Broadway shows, into restaurants and grocery stores,” Stoga says. “By the time our facility dogs get to a police department, they have had over 10,000 hours of socialization, which is the most in the industry.”

Though the dogs are being trained to calm traumatic events on the outside, they also bring relief behind bars, according to Stoga.

“These dogs help the entire jail. They calm the place down and bring smiles to everyone’s faces,” she says. “It brings humanity, joy and innocence into an environment that doesn’t have much of those things.”

Prison Led Training Experiences for Officers

By the time, these dogs graduate from the program, they’re more than just well-trained; they’ve built strong, lasting relationships with their incarcerated handlers, who in turn gain valuable skills and responsibility that can help them reintegrate into society. It’s a win-win scenario that transforms lives—both human and K9.

The next step is a two-week training scenario involving the new police handler and the inmate who trained the dog.

“We bring the officers, at our expense, to upstate New York for two weeks, where we house them, pay for their meals, and their transportation,” she says. “They go into the prison to be trained by the inmates who trained the dogs. We are unique in that we are the only program in the country that does that.”

Stoga acknowledges that the Puppies Behind Bars program helps break down barriers between people who might otherwise never interact. For both officers and inmates, the circumstances that led the incarcerated individuals to prison are often difficult and negative. These experiences can shape the way they view each other.

"The program creates a unique opportunity for both groups to see each other in a different light. They start to see each other as human beings," Stoga explains. "It encourages empathy, understanding, and mutual respect in a way that’s hard to achieve through traditional means. And I believe to the bottom of my socks that an incarcerated individual who has had a positive experience with a police officer will carry that on into their community when they are released. Their perceptions have changed forever."

Rotta says it was life-changing when he went into the prison to train with Eddie. “I saw a group of men who made mistakes and are giving back to society now,” he says. “These men feel worthy, are learning new skills, and have a sense of purpose.”

Rotta acknowledges that this program isn't suitable for all inmates, but for those who qualify, it's a great rehabilitation tool.

“I cannot think of anything they can do in prison that would impact as many people as this program,” he says. “It really changed my view on how inmates can be reformed to give back to society.”

Still, turning the dogs over to their intended handlers is a hard day for most inmates, Stoga admits. But, she says, it is also a day that makes them proud.

“For a lot of incarcerated individuals, it’s the first time they ever stuck with anything and didn’t walk away as soon as things got tough,” she says. “They know that because of their work, love and commitment, the dog is going out into the world to help someone. They are sad, but the overriding feeling is one of pride and a feeling of ‘I once took so much from society, but I am now contributing to society.’”

Recommendations for Success

Rotta has some recommendations for a successful Puppies Behind Bars experience. The first is to pick the right handler. They have to be dog people who wants to give back to the community, he says.

“This is a 24/7 commitment,” he explains. “The dog has to be with them all the time.”

The right officer also needs an assignment that aligns with the dog, he adds. Officers should be in an administrative or school resource officer role. They cannot be working patrol, Rotta says.

The second is the officer needs to be willing and physically able to exercise the dog every day. These K9s are still young and have plenty of energy. “They need to run. They love to swim,” he says. “The training socializes them and teaches them to be calm, but you still have to get out the energy out. Exercise, to me, is as important as the training.”

How to Get a Dog

Agencies interested in receiving a dog from Puppies Behind Bars must complete an application that provides detailed information about the department, the intended handler, and the dog's future home.

"The application asks about your department, the handler’s experience, where the dog will live, whether there’s a yard, if they will have time to exercise the dog, and how they plan to use the dog," explains Stoga. “The application ensures that each dog is placed in an environment where it will thrive and be fully supported in its role.”

Puppies Behind Bars donates to K9, but departments can expect the dog to cost about $2,300 a year in food, veterinary bills, and related K9 equipment. However, those expenses, says Rotta, pale in comparison to what the dog can do.

“It’s pretty much priceless,” he says. “There is zero negatives to having a dog like Eddie. It’s a win for the department, the officers, and the community.”

Learn more about Puppies Behind Bars and apply for a dog at: https://puppiesbehindbars.com/