In 2023, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) seized enough fentanyl-laced fake pills and fentanyl powder to cause over 388.8 million lethal doses.

Removing Risk from K-9 Fentanyl Training

Wyoming Highway Patrol and MakorK9 share how to train K-9s on fentanyl without the risk.

Reno, a female black lab paired with Trooper J. T. Dellos, was the first Wyoming Highway Patrol K-9 trained to sniff out fentanyl.

Wyoming Highway Patrol

U.S. overdose deaths related to fentanyl also soared 279% from 2016 to 2021, making it the leading cause of death in adults ages 18 to 45, according to the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention.

But until recently police departments did not train K-9s to detect this fatal drug.

While most police drug dogs are trained to detect a variety of illegal substances, it's only recently that police departments have trained K-9s to detect fentanyl. In fact, most jurisdictions lack K-9s trained for this purpose, reports Mark Rispoli, owner of MAKOR K9, an organization that has trained police K-9s since 1985.

According to Rispoli, departments avoid fentanyl training because of the risks fentanyl exposure poses to police dogs and their handlers. Fentanyl, he explains, is so lethal that inhaling or touching it can be fatal. Its toxicity is particularly concerning for police dogs who may encounter the drug as they sniff for other substances, he adds.

But as K-9 teams encounter more fentanyl in the field, this thinking has shifted. “Fentanyl has moved from being an independent drug to part of the recipe for other drugs,” Rispoli says. “Officers now routinely encounter cocaine, heroin and other drugs mixed with fentanyl.”

Capt. Marc Russell, District 3 commander and K-9 team commander for the Wyoming Highway Patrol agrees. He says the agency spotted the need for fentanyl training as K-9s encountered more poly-drug situations at traffic stops.

“With the significant issues we were seeing with opioids and fentanyl, we wanted to figure out how to tackle the issue head one. We realized we had to start with training our dogs,” Russell says. “But in training them, we didn’t want to create a safety concern for our dogs or their handlers.”

The Wyoming Highway Patrol collaborated with MAKOR K9 and Precision Explosives, a company that helps train K-9s with training aid and delivery devices (TADDs) charged with real narcotic odors. Together, they started a journey to train and certify K-9 units on fentanyl detection, and, in 2022, trained the first Wyoming Highway Patrol dog to detect fentanyl.

This dog was officially certified by the International Police Canine Association (IPCA), formerly the California Narcotic Canine Association, which was the first nationally recognized law enforcement canine association to establish certification protocols that emphasized safety to the canine team.

Since then, Wyoming Highway Patrol has put nine more dogs through fentanyl training. “The safety and success of this pioneering effort helped us expand this program to the rest of our narcotic detection K-9 handler teams," Russell says.

The Challenges With Fentanyl Training

The primary concern in training dogs to detect fentanyl is the safety of the dog and the handler, explains Russell. “We had to mitigate the risk of accidental exposure to the hazardous substance during training sessions,” he says. “Dogs may show aggression toward training aids that can lead to damaged packaging. We had to develop a way to train them safely.”

The initial option entailed was to utilize a pseudo (counterfeit) substitute, which attempts to mimic the smell of the actual substance. Rispoli says many departments use this training method. Because it’s not the real drug, he explains departments “do not have to account for it, it’s not a controlled substance. They can spill it, leave it, burn it, etc. It’s not lethal and it’s not dangerous.”

Rispoli questions the effectiveness of this training because it increases the odors dogs get trained on. He explains, “When you train a dog on pseudo cocaine, heroin and methamphetamine, for example, and then you train the dog on the real odor, you are training them on six odors instead of three. This can confuse the dog and open up the case for legal challenges should a case end up in court.”

He shares it is the position of the ICPA and MAKOR K9 that by using pseudo substances to train narcotic detection dogs, departments substantially risk invalidating using the dog for probable cause as it applies to the 4th Amendment. “You are training your canine on substances that are not contraband and are not in any way illegal to possess,” Rispoli explains.

Rispoli had used specialized training aids that infused laboratory-grade filters with real drug odors from Precision Explosives in the past and discovered the company had a fentanyl product that allowed dogs to detect fentanyl without direct exposure to the substance.

Precision Explosives takes an impermeable laboratory filter about the size of a 50-cent piece and infuses it with fentanyl odor. This filter is then placed in a plastic or glass training aid. “There is no actual fentanyl in the filter, just the odor,” Rispoli adds. “If the dogs came in contact with the filter, it would be harmless.”

Rispoli emphasizes the convenience of the filters' small size. “They can be put in a suitcase or backpack, or a a compartment in a vehicle, where the dog can safely train on it,” he says

The Wyoming State Patrol agreed to train a single dog on fentanyl after Rispoli showed them the Precision Explosives product. “We started with the Precision Explosives training aid, then moved to pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl,” Russell says. “We trained our dogs to find the odor on the first day. On the second day, we introduced the actual product. The dogs performed really well on both.”

Training With the Live Drug

Rispoli stresses the importance of training with the purest form of the target scent, enabling dogs to fully grasp the scent profile. Later, he says, using live drugs ensures police dogs can identify the substance accurately in real-world scenarios. This also limits potential legal challenges related to court proceedings.

Rispoli used pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl in the second part of the training, which came with a few challenges.

“I want to train dogs on the purest form of the product I can find, which is the actual product,” he explains. “This ensures the dog's chemical picture is as clear as it can be. Because though dogs are the best living, breathing biosensors that exist, they are not perfect.”

The Wyoming Highway Patrol worked with Rispoli to put live drug inside the Precision Explosives’ impermeable membrane and then inside a plastic training container. “We added an extra layer of tape on the outside to make sure the lid didn’t unscrew or anything like that,” Russell adds.

The department also took measures to keep the product safely locked up. Russell explains they keep live fentanyl locked in a Pelican case in a secure evidence locker at district headquarters. The department mandates that teams check out the product, just like with evidence, to create a log of its use.

The department also has just one fentanyl training aid on hand for the entire state. “We restrict when and how it can be used in group training. Usually, me or my team coordinator checks it out and transports it around. We wanted an elevated level of accountability to make sure that it is always accounted for,” he says. “We also glove up when we package it and place the training aids where dogs cannot access them.”

The department also uses 200-mg pharmaceutical-grade fentanyl. “We imprint the dogs on that and the live odor,” he says. “It’s a quick process.”

According to Russell, the department's K-9s are trained in multiple drug categories, making fentanyl training a matter of introducing another scent and reinforcing their ability to differentiate. “You’re asking a dog to discriminate five odors out of the millions of odors they are exposed to in the world,” he says. “But the dogs pick it up within a day or so, and as we move through the week, we reinforce that behavior over and over.”

Ongoing training is also necessary, he adds. Wyoming Highway Patrol requires a minimum of 16 hours of narcotics odor training every month. The department also hosts quarterly regional training where all handlers train as a group. “Within that 16 hours, K-9s are training in marijuana, heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine. We make sure the handlers pull out all five odors and cycle them through their training regularly and equally,” he says.

As an extra precaution, the department also keeps extra Narcan (naloxone) on hand, although most officers already carry it on their uniform. Narcan is administered to dogs if they show any signs of exposure, which includes suppressed respiration, lethargy, and stumbling.

Wyoming Highway Patrol has had great success with its K-9 team training on fentanyl detection.

Wyoming Highway Patrol

Adding in Certification

The next issue was certification, Rispoli says. “The process worked, but we needed to certify the dog,” he says. “But there wasn’t any such certification available.”

Rispoli, a founding member of the California Narcotic Canine Association, now known as the International Police Canine Association (IPCA), reached out to President Rob Havice about developing a fentanyl certification. The two men worked together to develop training and certification standards.

“When it came time to certify Wyoming’s dog, we did it,” he says. “We became the first canine organization in the country, and possibly the world, to certify a law enforcement dog for fentanyl.”

Though Russell is an IPCA-certifying official, Wyoming Highway Patrol relies on an outside IPCA official to certify its dogs. “We want to get a fresh set of eyes,” he says. However, Russell can certify dogs from other departments.

Things have exploded since then, with MAKOR K9, the Wyoming Highway Patrol and the IPCA fielding calls from all over the globe. “People wanted to know how the training works, what we did to make it safe, and how to do it,” Russell says. “They come in to audit our training, and to see how we’re packaging and safely handling the live fentanyl training aide. We’ve also received a lot of requests for certification.”

Russell and Rispoli are happy to extend a helping hand to agencies seeking guidance on fentanyl training protocols and safety measures. They encourage agencies to contact them via email. Rispoli can be reached at mark@makork9.com or by calling (707) 484-3769 and Russell at marc.russell@wyo.gov. The IPCA certification can be viewed at www.cnca.com.

More Special Units

Ohio’s Statewide Drone First Responder Program to Take Flight

Over the next two years, the Ohio DFR Pilot Program will equip municipalities with advanced drone systems, deliver comprehensive training for first responders, and enable FAA-approved Beyond Visual Line of Sight operations.

Read More →

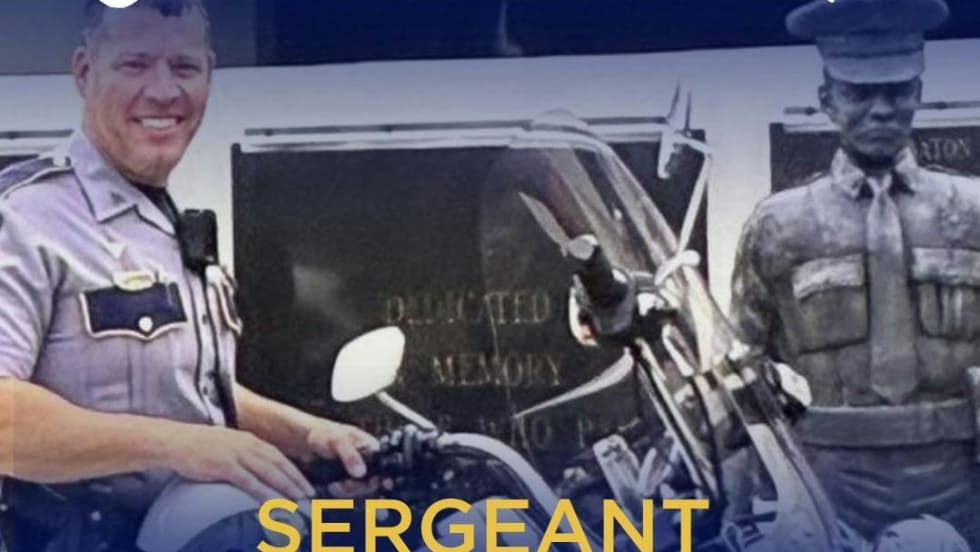

Louisiana Motor Sergeant Dies from Injuries Suffered in June “Intentional” Crash

A motor officer, Sgt. Caleb Eisworth was on his way to participate in a funeral escort when he was struck by another vehicle.

Read More →

Tennessee Officers Say Man Tried to Detonate IED During Arrest

Inside the bedroom officers found what they believed to be an IED. The officers evacuated the house and called for the Chattanooga Police Bomb Squad and ATF agents.

Read More →

Florida School Officer Dies After On-Duty Medical Emergency

Sergeant Greg Graff was “preparing school leaders for the upcoming year during a safety training program at Clearwater High School,” the school district said.

Read More →

Grenade is Missing from Explosion That Killed 3 LASD Deputies

ATF Special Agent in Charge Kenny Cooper said definitively that only one grenade detonated at the facility on July 18.

Read More →

Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department Names Deputies Lost in Friday Explosion

LASD said Detective Joshua Kelley-Eklund, Detective Victor Lemus, and Detective William Osborn who were all assigned to Special Enforcement Bureau’s Arson Explosives Detail were killed in the incident.

Read More →

Maryland State Police Helicopter Rescues Victim from Overturned Boat in Chesapeake Bay

The Maryland State Police Aviation Command Trooper 7 crew, the MSP helicopter based in California, Maryland, were monitoring the county dispatch radio, overheard the dispatch, and self-launched.

Read More →

3 Los Angeles County Deputies Killed in Explosion Friday Morning

At press time the names of the deputies had not been released. Sheriff Robert Luna said one had served for 19 years, another for 22 years, and another for 33 years.

Read More →

Georgia Sheriff’s Deputy Fired After K-9 Dies in Hot Patrol Vehicle

The vehicle’s air conditioning failed because of a malfunctioning compressor and its heat alarm did not function, according to the sheriff’s office.

Read More →

South Carolina Sheriff’s K-9 Dies After Training Session

Deputy Saunders rushed Sam to the vet as soon as soon he noticed the dog was in distress after the training, the sheriff’s department said.

Read More →