At Columbine, the officers, deputies, firefighters, and emergency medical personnel did an incredible job in their response to an unbelievably bad situation. But through no fault of their own, the tactics they were trained to use were not suited to the nature of the incident.

For the past 20 or so years the operational philosophy of most American law enforcement agencies has been highly conservative with regard to officer-suspect confrontations. This has been especially true when such incidents have involved innocent bystanders or hostages.

Law enforcement strategists once believed that time was on the side of the responding officers in such incidents. We could wait out the situation. We could just bide our time until the suspect sobered up, got tired or hungry, or just came to his or her senses. Our job as first responders was to establish a perimeter, evacuate the public around the scene, call for the tactical team and the negotiators. And wait.

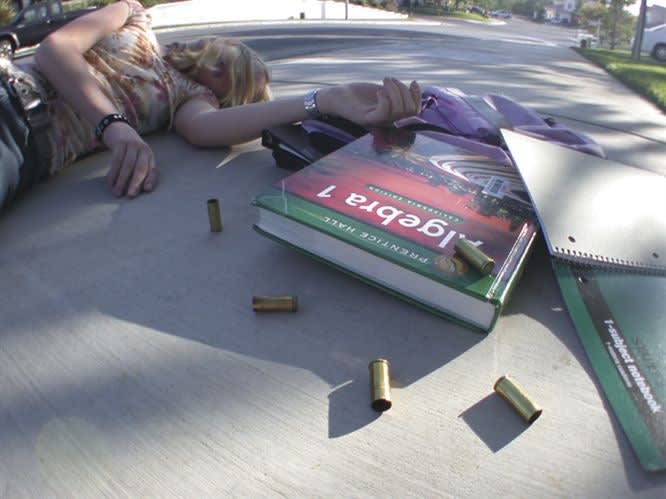

But that changed on April 20, 1999, the day two students at Columbine High School in the Denver suburb of Littleton, Colo., made a concerted effort to kill all of their classmates and teachers.

At Columbine, the officers, deputies, firefighters, and emergency medical personnel did an incredible job in their response to an unbelievably bad situation. But through no fault of their own, the tactics they were trained to use were not suited to the nature of the incident.

Did that strategic flaw lend itself to a greater body count for teen killers Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold? It's hard to say. What is known is that Harris and Klebold killed 13 and injured 22. And regardless of tactics, the casualty figure would be much higher without the courage and skills of the responding public safety and emergency personnel.

And some good has come out of the tragedy. Since Columbine, law enforcement nationwide has developed "new" operational philosophies to cope with the "active shooter" incident.

The communities we serve have spoken and what they have told us is that they have an expectation of their law enforcement officers to take immediate action to neutralize active shooters and rescue victims. This change in operational philosophy represents the most abrupt paradigm shift I've seen in policing during the last 20 years.

Taking Action

The San Diego Police Department, where I work in the in-services training division, has developed a special program called "Field Response to an Active Shooter Situation," and all of the agency's 2,500 sworn officers are required to complete the course.

Many officers are usually less than enthusiastic about such mandated training programs, but the initial student evaluations for this program have been glowing. One typical comment that we have received reads, "It's about time we were allowed to do what we became cops for in the first place."

Here's a look at some of the most important aspects of the San Diego PD's active shooter response training program.

In an active shooter incident, patrol officers will likely be the first law enforcement to arrive at the scene. This is true in almost all shooting or hostage incidents, but in this "new" operational philosophy, first responders will not be expected to call for SWAT and wait until the team arrives. If immediate intervention is appropriate, the expectation is for the first responders to take action.

But it's important to understand that the decision for the first responding officers to act must be accompanied by a reasonable likelihood of success. No one expects you to undertake a suicide mission. If the active shooter(s) is using fully automatic weapons, armor piercing rounds, and wearing body armor, no one in his or her right mind would march right in with just a 9mm Glock at port arms and expect to come out in one piece.

That said, however, you do have to jump into this fire. And doing so without sound planning and strong tactical awareness could lead to increased police and civilian casualties. Your primary goal as a first responder at an active shooter incident is to save as many lives as possible. And the way you achieve that goal is by locating, isolating, apprehending, or eliminating the threat.

Success or failure at an active shooter incident is determined by advance planning. Your agency needs to train each officer to play a role in eliminating/apprehending the bad guys, or assisting in the rescue of the victims. And these roles and the duties involved should be well understood before an active shooter incident occurs.

Contact Teams

Eliminating/apprehending the bad guys is the job of what the San Diego PD calls a "contact team." The mission of the contact team officers is to align themselves in a formation that is tactically sound for the given circumstance and to move toward the shooter or toward the sound of gunfire.

Should the gunfire stop, the contact team will slow down and re-evaluate the situation. At that juncture, a decision must be made to continue, or to lock down the area. Also, the contact team must be flexible enough to quickly transition into a rescue or containment team, depending on how the mission evolves.

Each contact team consists of four to six officers differentiated into a leader, a point officer, flankers, grabbers, and a rear guard.

The contact team is assembled and directed by the leader. Additionally, he or she maintains radio contact with communications regarding areas that need rapid containment, areas currently being searched, suspect location, and victim location.

The contact team's leader should call up the "rescue team" to evacuate or lock down cleared areas. He or she should advise responders of the number of victims and their location. As the search progresses, the responders may need to call additional personnel for security and containment. If the situation dictates that the key is to wait, gather more information, advise of suspect(s)'s movements and location and coordinate containment, then the contact team leader must make a judgment whether to wait or to deploy.

Another key member of the contact team is the point officer. The Point Officer covers all areas ahead of the team whether it is operating in a T-formation, a diamond formation, or in search mode.

Because the point officer is most likely to make first contact with the shooter(s), he or she should be armed with a long gun such as an AR-15, MP5, Ruger PC-9, or other carbine. A shotgun is not the weapon of choice in this situation unless it is loaded with slugs and equipped with a precision aiming device.

As the contact team formation moves toward the shooter(s), the point officer should use standard building search maneuvers such as "cutting the pie" or "quick peek" tactics when entering new areas. Ambushes are likely because the shooters are expecting or even counting on police intervention.

Flankers or "searchers" cover the formation's flanks and assist the point officer while in a T-formation. These officers are responsible for making entry and searching rooms and other areas as directed by the team leader.

The flankers should be prepared to challenge and apprehend the suspect or suspects if encountered. If a suspect is encountered, it is crucial that all the officers remain in formation to provide cover and guard against a second or unknown suspect.

Another job that falls to the flankers is to debrief any apparent victims as the contact team passes to be sure they are not suspects. This intelligence must be passed to the team leader as it is gathered.

The final piece in the contact team puzzle is the "rear guard." Officers assigned to rear guard duty do exactly what the term implies. They cover all the team members from attack from behind, whether in T-formation or search mode.

Active shooting incidents are characterized by confusion and anxiety, and friendly fire accidents are a very real danger. Consequently, it's advisable to organize the contact teams using uniformed officers or easily identifiable personnel wearing brightly colored raid jackets.

If there are multiple suspects operating independently, you may need more than one contact team. This can be tricky, especially in a situation as hazardous as an active shooter incident. So be sure to coordinate the movements of the teams.[PAGEBREAK]

Rescue and Containment

Rescue teams and containment teams have the same basic organization as contact teams. The only difference is their missions. A contact team's job is to end the threat; a rescue team's goal is to aid the victims.

But a rescue team is still a police operation and does not involve emergency medical personnel. A rescue team is made up of a minimum of five to six sworn and armed police officers.

And a rescue team acts like an armed unit. If rescue attempts are made in danger zones, the rescue team's movements should be conducted from a "T" or diamond formation just like the contact team. The formation should only be broken when the suspect(s) has been neutralized, contained, or barricaded.

Like the contact team leader, the rescue team leader is charged with assembling and organizing his or her team as soon as possible after arriving at the site. The leader's first priority is to assign a second in command and to organize the team members according to their respective tasks. He or she then directs the team based on visual observation of downed victims or by directions provided by the contact team leader.

One critical difference between the jobs of the rescue team leader and the contact team leader is that the rescue team leader must choose a safe location as the evacuation point for the victims. Then before deploying, he or she needs to be sure that all of the team members are on the same page.

Also, as an armed police unit, the rescue team has to be ready to do battle. It has to be flexible, trained in rescue and combat. For example, if the rescue team confronts the suspect(s), it must change into a contact team.

For this reason, the rescue team's point person and flankers should wield long guns whenever possible. They need to form a tight shoulder-to-shoulder line and provide protection from all areas ahead and to the side. These team members must also move quickly past downed citizens or even officers and hold their position while the "grabbers" perform their job. Officers assigned as grabbers lift the downed victims and advise the team leader when they are ready for retreat.

Finally, do not lose sight of the overall goal. Save as many lives as quickly and as safely as possible. If you are the first responder on scene, you may need to partially enter the building to effectively coordinate the next responding officers. But don't enter the danger zone alone.

If assigned to a contact team, remember discipline is paramount to a successful operation. Don't focus on rescuing the victims and don't let first aid become your priority. Stopping the suspect is the primary goal and that will save more lives than any other action you can take.

Active Shooters

One of the first things addressed in San Diego PD's new active shooter response program is the definition of an active shooter.

An active shooter incident is the intentional random or systematic shooting of multiple victims in which the shooter(s)'s intent is to continue the spree until stopped by law enforcement or suicide. Although identified primarily with school shooting, active shooters can involve any workplace, school, church, etc. And regardless of law enforcement response, the likelihood of innocent people being killed is great.

For the shooter(s), this is often a final act in a twisted or desperate life. Investigations have revealed that many active shooter suspects preplan their massacres in detail. However, the one thing they rarely include in their plans is an escape path. Active shooters are usually prepared to commit suicide either by law enforcement action or by their own hands.

Do It Yourself

One of the most critical factors in successfully neutralizing an active shooter is to have a plan and to implement it as quickly and efficiently as possible.

If your agency doesn't have an active shooter response plan, get with other officers working in your area and design a basic tactical response. At a minimum, develop a strategy for containing the problem and reducing the number of casualties.

Active shooter incidents often involve more than one agency, so in your planning be sure to involve your most likely partners in your area. If the bullets start flying, it's critical that everyone is on the same page of music.

Team Tactics and Movements

While in the "danger zone" of an active shooter incident, contact and rescue teams should operate from a T-formation or diamond formation.

There are many differing opinions on the attributes of using one formation over another. Usually, the situation determines the formation. The San Diego Police Department has chosen to use the "T" as its primary formation. In contrast, the San Diego Sheriff's Department uses the diamond. In either case, all officers in your agency should be trained in both tactics and allowed the discretion to use their choice when they feel it would be more beneficial.

For example, the T-formation provides point, lateral, and rear coverage as a team moves through hazardous areas. However, don't stay in T-formation during entries. All room entries should be made with two-person entry techniques, using pie-cutting, quick peeks, and blocking tactics.

The Diamond formation works very well and should be used in close quarters. At a minimum, four officers are needed for this formation to provide maximum protection and fire power. Five is even better with the team leader in the center. Remember, in the diamond position, the point person can change depending on the direction of the formation.

Finally, regardless of what formation you choose do not pass on an un-searched area, unless you are sure of the location of all suspects.

Active Shooter Incidents

Columbine High School, Littleton, Colo., (April 20, 1999)-Two students armed with rifles, handguns, and explosives executed an elaborate plan, killing 13, wounding 22 others, and setting off several bombs. After engaging the first responding officers in a gun battle, both suspects committed suicide.

Thurston High School, Springfield, Ore., (May 21, 1999)-15-year-old Kip Kinkle armed with a .22 caliber rifle killed two and wounded 20. Kinkle murdered his parents the day before the school shooting. He was arrested at the scene.

Jewish Day Care Center, Los Angeles, (August 11, 1999)-37-year-old Buford Furrow armed with a semi-automatic weapon fired 70 shots wounding three children and two adults at a day care center. Furrow then killed a postal carrier during his escape. He eventually surrendered in Las Vegas.

Santana High School, San Diego County, Calif., (March 5, 2001)-15-year-old Charles "Andy" Williams armed with a handgun shot and killed two students and wounded 13 others. He then barricaded himself in a restroom. San Diego County Sheriff's deputies and an off-duty San Diego Police officer arrested Williams.

Granite Hill High School, San Diego County, Calif., (March 22, 2001)-A student shot and injured five before being wounded during a running gun battle. He was apprehended by a school police officer.

Gutenberg School, Erfurt, Germany, (April 26, 2002)-A 19-year-old expelled student armed with a shotgun and a handgun killed 14 teachers, two students, and the first arriving police officer. The suspect then committed suicide.

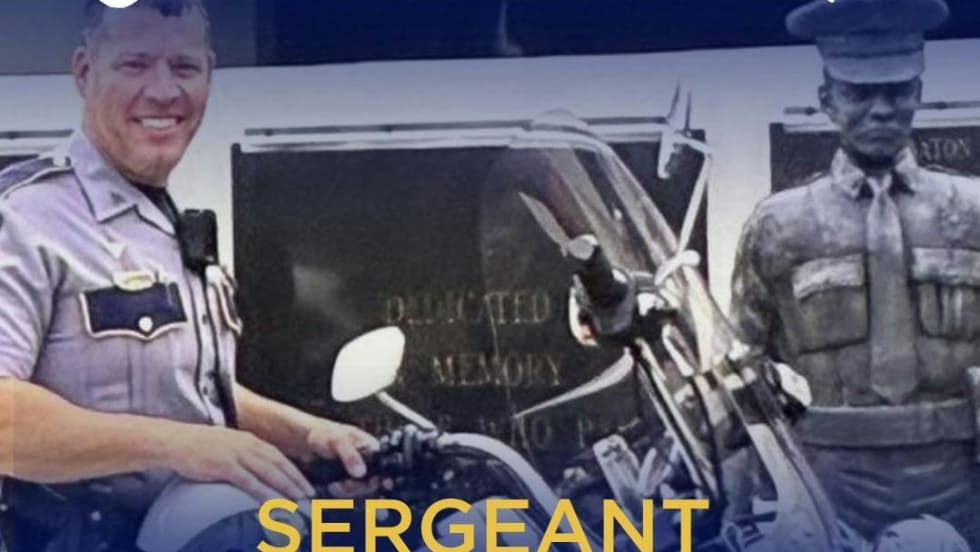

Dave Douglas is a sergeant on the San Diego PD with 25 years of service. He helped develop the agency’s active shooter response training program as a member of the in-service training division.