Today's hostage negotiators are called "crisis negotiators." And with good reason. Today the responsibilities of these officers reach far beyond talking down hostage takers and now include suicide intervention, high-risk warrant service, and counter-terrorism operations.

The job description of a police negotiator used to be pretty much limited to persuading barricaded suspects to release their hostages and surrender. Accordingly, these dedicated officers were once called "hostage negotiators."

Today's hostage negotiators are called "crisis negotiators." And with good reason. Today the responsibilities of these officers reach far beyond talking down hostage takers and now include suicide intervention, high-risk warrant service, and counter-terrorism operations.

Inside the CMU

To get a feel for the duties of crisis negotiators, let's take a look at the inner workings of the crisis negotiation unit of Washington, D.C.'s Metropolitan Police Department.

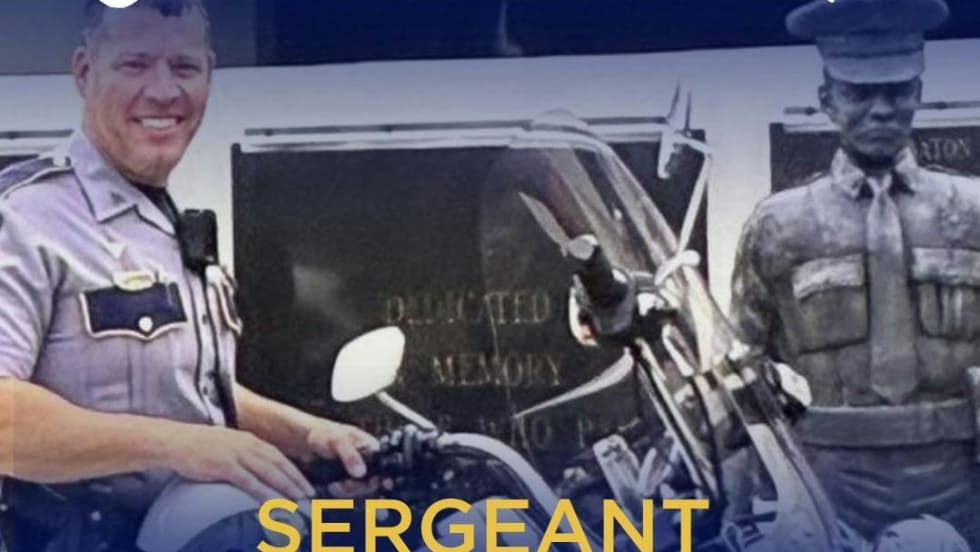

MPDC's Crisis Management Unit (CMU) is part of the department's Emergency Response Team (ERT). The CMU consists of eight officers, a sergeant, and a lieutenant all trained at ATF and FBI negotiation schools.

The CMU team trains with and is called out with the ERT tactical team. In addition, the negotiators hone their skills constantly with in-house and outside academic instruction, practical role-playing scenarios, and real-life telephone suicide mediation.

Case Study

The following is an actual case from the files of the CMU.

On a recent unusually warm October morning in the nation's capital, Officer Robert Underwood of the MPDC was working patrol in the Sixth District when the morning calm was broken by gunshots. He was called to the corner of 30th Street and Anacostia Road, where he discovered a totally nude man standing on the sidewalk, clutching a 9mm handgun in his right hand.

Seeing Underwood, the man turned, snapped off two rounds, and ran. Neither of the shots hit Underwood. He called for backup.

As police reinforcements arrived and started to comb the area, another officer caught sight of the naked suspect a couple of blocks away. The suspect had ducked into an apartment building on Nelson Place and taken refuge in a room on the second floor. The officer recognized the suspect as a known drug user from the area with an extensive criminal history.

Other Sixth District officers arrived and formed a containment perimeter, while a preliminary investigation was conducted. The subject failed to respond to all attempts to communicate. And too many unanswered questions remained. Were there any hostages or accomplices with him? Were there more weapons in the apartment? What was the tactical layout of the building and the potential escape routes? Were drugs involved?

Facing all of these unknowns, the on-scene street sergeant requested the services of the Emergency Response Team, which includes the Crisis Management Unit.

The Callout

As shots were being fired down in the Sixth District, Officer Sinobia Brinkley was sound asleep in her suburban Maryland home. Brinkley, a member of the MPDC's crisis negotiation team was abruptly awakened by the piercing sound of a pager alert.

Brinkley's "electronic leash" flashed an all-too-familiar number. The seven-year veteran of CMU glanced at the readout, saw that ERT was being mobilized, and rolled out of bed. She wiped the sleep from her eyes and called the MPDC's Synchronized Operations Command Center for the location and broad details of the incident.

ERT was being summoned to Nelson Place to deal with an apparent barricade situation. Hurriedly, Brinkley dressed for work, grabbed her keys, and took off out the door. While traveling toward D.C., she tried to mentally digest the limited available information in anticipation of her arrival on the scene.

ERT Roles

The ERT gathered at the mobile command center bus for an impromptu briefing. Additional details had surfaced from an area canvass; it was learned that the suspect had barricaded himself in his mother's apartment in an unplanned, spontaneous attempt to avoid capture. Also, the ERT members learned that the suspect was a known drug user and that it was believed his erratic behavior could be attributed to "dippers," cigarettes treated with liquid PCP.

As it had in 55 other deployments that year, the MPDC's incident command started implementing its command and control procedures, coordinating units, establishing community and media liaisons, and maintaining interdepartmental logistics.

The remaining tenants of the apartment building were evacuated to a peripheral safe zone. Patrol officers were repositioned to the outer perimeter, allowing the tactical ERT officers to take over the inner containment boundary. And the CMU negotiators went to work.

Sgt. Kevin O'Bryant, CMU team leader, assigned Brinkley and Officer Haywood McGregor as primary and secondary negotiators, respectively. Brinkley got the nod for her convincing verbal ability in previous barricade situations.

McGregor, a 19-year veteran of MPDC, is a seasoned negotiator with an uncanny knack for running a tight ship. During this incident, he maintained order for his lead negotiator, thereby allowing her to concentrate fully on the discussion. The remaining members of the CMU team assisted by taking on assignments such as timekeeper and other support positions in the negotiation.

Contact and Conversation

Before CMU attempted to establish further communications with the suspect, it needed more information. A local and NCIC criminal history was compiled. In addition, interviews with the suspect's family and friends were conducted to give the negotiators a picture of his mental and physical health, relationship and financial status, religious faith, military involvement, and sleeping and eating patterns. This in-depth intel is critical as it gives the negotiators a more complete picture of the barricaded subject, allowing a precise dialogue.

While other MPDC officers and detectives gathered intel for the negotiators, the CMU contacted the telephone company and the line to the apartment was seized. This measure prevented the suspect from dialing out or receiving calls from anyone but the negotiator.

With the ERT in position, the phone company on board, and intel in hand, Brinkley decided to initiate contact. As often happens in these situations, her first attempts were fruitless. Brinkley tried five times in the first hour to call the suspect. Each time the suspect picked up the phone, listened for a second, and hung up.

But in crisis negotiation, persistence pays off. And on the sixth call, the suspect engaged Brinkley with a response. "Who are you and what do you want?" he yelled into the phone.

Brinkley knew this hostile and frightened response likely represented her one chance to establish a conversation with the suspect, so she answered him. "I'm Sinobia Brinkley with the police; you can call me Snow. I'm here to help."

The suspect retorted, "The police...I didn't do anything."

Brinkley's primary concern at this stage of the incident was to establish that the suspect was alone. She asked him, "Sir, is your mother in there with you?"

There was no reply.

Needing answers, Brinkley decided to play one of her hole cards. The officers and detectives who had investigated the suspect's background had discovered his street name. She knew it was time to use it. "Listen, Joone, is anyone else in there?"

The strategy worked. "No, just me," Joone replied and the dialogue between the two began.

"Just you?" responded Brinkley, as McGregor in the background suggested more one-on-one rapport-building to gain the suspect's trust.

Talking Strategy

In crisis negotiation what the subject says is much more important than what the negotiator says, and the negotiator's use of active listening techniques allows an avenue of release for the offender's built-up anxiety and frustration. Also, this problem venting allows the negotiator to suggest possible alternatives to the subject's plight. Over time, his emotional state and perception of the events will divulge valuable hints.

After contact was established in the Nelson Place incident, Brinkley quickly realized that the suspect had a sense of despair in his voice and things were clearly coming to a head. His earlier rush of adrenaline had subsided, as had his PCP buzz.

Things were falling into place for the negotiators. And then they received a really positive piece of news. ERT tactical officers had recovered the suspect's semi-automatic outside of the building. That could mean that he was no longer armed or it could mean that he no longer needed it because he had other weapons in the apartment, but it was still a good sign.

The interactions between Brinkley and the suspect went smoothly for two hours, and a kind of informal bond seemed to be developing between them. Brinkley displayed concern for the suspect by asking, "Are you feeling okay?" He answered, "I'll tell you, Snow, I'll be doing a lot better when I get outta here." The door was open for Brinkley to end the standoff. She asked him to give up and, surprisingly, he agreed.

Trust Me

Brinkley notified the tactical team that the suspect was coming out. But as the suspect peered from the apartment door, he caught sight of two heavily armed ERT officers in their tactical black uniforms, and abruptly slammed the door.

The suspect picked up the phone and started yelling at Brinkley, "You're lying to me! You ain't the police. You're scamming me. You wanna bust a cap in me!"

He hung up.

All efforts to telephone the suspect over the next 30 minutes were futile, and the CMU team members gathered to brainstorm a solution. There was a possibility that the incident could easily turn into a suicide situation or an escape attempt. It was decided that Brinkley had to reestablish contact to stabilize the suspects' perception of lost control.

It was touch-and-go for 20 minutes. Then finally, telephone contact was reestablished. It was then that Brinkley learned that the suspect thought the tactical field-dressed officers were rival gang members out to shoot him.

Successful conclusion of this incident would hinge upon Brinkley's ability to deftly convince the panicked suspect that the tactical officers would not shoot him if he surrendered. It wasn't a simple task given the conditions and the suspect's mental state. Brinkley talked with the suspect, listening for subtle clues to his emotional state. "You're going to kill me...I know it," he kept saying.

Brinkley countered with her word that no harm would come to the suspect if he followed her directions for surrender. Still, he was not comfortable with the terms.

End Game

In a highly unusual move, Brinkley agreed to let the suspect exit the apartment for surrender with the telephone to his ear. That way she could keep talking to him and reassuring him while he was being taken into custody.

The suspect agreed to the terms, and the information was relayed to the tactical team, so that they would not mistake the telephone for a weapon. Then with everyone clear on the conditions, the second attempt at surrender began.

After a few hesitant moments, the suspect slowly swung open the door to the apartment, and ERT Sgt. Charles Yarbough and the tactical surrender team took over the operation. "Come out slowly with your hands above your head!" shouted Yarbough.

The now-clothed suspect tentatively appeared in the doorway. In his left hand was a cordless telephone firmly pressed up to his ear. He unsteadily raised his right arm high in the air. Following Yarbough's orders, he began to shuffle in a small circle, giving the surrender team a chance to look for secreted weapons on him from a safe distance.

Over the phone, Brinkley spoke calmly to the suspect. "Take it slow, you're doing fine, Joone. Just do as he says."

Yarbough continued his surrender instructions. "Slowly get down on your knees and cross your ankles. Now lie flat on your stomach. OK. Place your arms out to your sides at shoulder height, palms out, thumbs up." The suspect hesitated for a moment. "Do it! Now!" Yarbough barked. The suspect obeyed.

Satisfied with the suspect's position and that he had no visible weapons, Yarbough gave his team the sign. Contact and cover was initiated, and the suspect was handcuffed and searched, and then led away for processing.

The ERT members and the CMU officers had successfully brought the incident to a conclusion with no bloodshed.

The MPDC's Nelson Place standoff may seem like a fairly routine tactical call out and perhaps something that could have been handled by first responders. But a search of the suspect's apartment revealed why it's much better to contain a barricaded subject with a tactical team and try to talk him out than attempt some kind of cowboy heroics. A sweep of the apartment turned up a shotgun and four shells. The patrol sergeant clearly made the right call when he requested ERT.

After-Action Reports

After the incident, the entire ERT, including CMU, was called in for a mandatory debriefing. This is standard procedure, and it allows the team to evaluate its overall performance and discuss any problems that may have been experienced in the field.

Additionally, the negotiation process is always taped. In the Nelson Place incident, this allowed Officer Brinkley and the rest of the unit to review the proceedings as a training tool. It was also utilized by the MPDC's training academy to give new recruits an idea of what takes place during an actual callout and why their role as primary responder in patrol is so important.

As it happened, this was a close to flawless deployment, with few glitches. All team members, as well as the street officers, functioned in an effective and efficient manner, limiting the standoff to just under three hours and ending it without violence.