Sgt. Burnett had worn the vest religiously throughout his career, but on this day he told his wife that for the first time he would go to work without it. She wasn't happy with his decision.

Though it had been an unseasonably hot month, the overcast May sky outside Troy Burnett's window did little to buoy his spirits. Normally, the spring rain would be a welcome relief for the Ogden, Utah, police sergeant.

But caught literally between the weather and his ballistic vest, the skin on Burnett's back had developed an insufferable rash and he suspected that the dampness in the air would be of little help. Burnett glanced at the culprit vest, that same vest that he'd donned thousands of times before, and something chaffed within him at the thought of putting it on. He knew that if his irritated skin was going to breathe, it needed a break.

Burnett had worn the vest religiously throughout his career, but on this day he told his wife that for the first time he would go to work without it. She wasn't happy with his decision, and as he left his house he thought he heard her say he was being "a dumbass." He wondered if she didn't have a point.

Familiar Faces

Shortly after noon, Burnett rolled to meet some fellow officers for lunch when he noticed that a Utah state trooper had stopped a Ford Probe near the intersection of 12th and Porter. He flipped a U-turn to assist.

Burnett recognized the trooper as Chris Turley, recently off training. Turley explained to Burnett that he suspected the female occupant had been lying to him. By mutual accord, the officers approached the Probe, Turley on the passenger side of the vehicle, Burnett on the driver's side.

The sleeved tattoos of the driver's arms were the first thing Burnett recognized as he approached the driver. Billy Maw was a high-level white supremacist with Secret Aryan Warriors (SAW), a prison gang.

Burnett's and Maw's paths had crossed before when Burnett worked Narcotics. He'd been to the con's residence several times in response to complaints of Maw's drug activity.

In the two years since Burnett's last contact with Maw, the man had finished another prison stint. Now, he was out and under a federal indictment behind a wiretap. So Maw knew one thing that Burnett didn't—just where this traffic stop was headed.

Turley resumed his conversation with the female passenger. Like Maw, she was a methamphetamine addict, as well as a parolee at large.

As Turley dealt with the woman, Burnett observed that Maw—apparently oblivious to his presence—was digging between his seat and the center console.

Burnett yanked open the driver's door of the Probe.

"Hey, Billy, you need to put your hands on the steering wheel."

Startled, Maw greeted Burnett and complied. A conversation developed between the two men, the kind of agreeably stilted dialogue commonly shared between cop and con.

Meanwhile, Turley asked the passenger to step out of the car. He spoke to her long enough to get the information he needed to cross-check her story, then told her to get back inside the Probe. Turley returned to his patrol car, leaving Burnett to maintain vigil over the two.

She immediately started digging through her purse, and Burnett yelled at her to put her hands on the dash. She complied.

We Need Backup

Burnett was becoming more than a little frustrated. As a matter of practice, he preferred to exert a strong command presence during contacts, to keep control of situations in the manner he'd become accustomed to. He also had a fundamental philosophical disagreement with Turley's decision to place the female passenger back in the vehicle.

But it was not his stop or his call—it was Turley's.

Still, Burnett knew just what they were dealing with. If only he could have communicated as much with Turley, then the trooper would probably have taken the stop to the next level. But with the trooper inside his patrol car and no shared radio frequencies between the two agencies, there was not much he could do to get Turley's attention without compromising his standing with Maw.

He also knew that if he could get a third set of eyes at their location, he could get back to speak with Turley. Keeping the driver's door of the Probe open and his eye on the two occupants, Burnett keyed his mic and made his latest request for backup. After several attempts, a unit finally acted up, just minutes out.

Slightly relieved, Burnett continued his conversation with Maw. For a con, Maw had proven to be as respectful as one could expect, even deferential on occasion. Burnett had even come to expect a kind of casual chitchat from Maw.

[PAGEBREAK]

But today Maw's hands were grinding against the steering wheel, so tightly that the tattoos of his muscular forearms became animated. He complained of the cold and rain, and protested against Burnett's keeping the car door open.

Burnett refused to close the door, a decision that didn't set well with Maw, who continued to protest. Burnett reminded Maw that he was the one standing outside and getting even more wet. As he replied to Maw's complaint, he thought about how all this moisture was going to play hell with his back.

Some 15 minutes after his own arrival, Burnett's backup, Officer Aaron Hawes, arrived on scene.

Burnett instructed Hawes to stay with Billy Maw, telling the young officer to keep the door open and that if either of the vehicle's occupants didn't comply, "Do what you have to do."

It's not that Burnett didn't have faith in Hawes—or Turley for that matter. He did. But he also knew that both men were only recently off training, and neither had been on patrol long enough to recognize just how far and fast things could go south in a hurry.

Let's Hook Her Up

That's why he didn't waste time or pull punches when he approached Turley back at the trooper's patrol car. He advised Turley of Maw's criminal history and the fact that the man was a white supremacist known to be routinely armed.

Turley replied, "Well, she's lying to me, so let's go ahead and hook her up."

Burnett rejoined Hawes on the driver's side of the vehicle as Turley took the woman out of the car, placed her in handcuffs, and walked her back to his patrol car.

With the woman in custody, Burnett told Maw to step out of the car.

The 5-foot-9-inch, 200-pound ex-con stepped out. As he did, the wallet he had chained to his waist fell to the ground. Hawes later noted that Maw's eyes grew saucer-like in response.

Maw's agitation was even more apparent now and getting worse by the second. Burnett attempted to calm him.

"Billy, you're not under arrest," Burnett told him. "But I'm going to pat you down. Put your hands behind your head."

With that, he tapped Maw on the back of his head to indicate where he wanted the con to put his hands with his fingers interlaced.

Hemming and hawing, the con appeared momentarily unsure as to what course of action he should take. He raised his hands as though he would comply.

Then he bolted.

As Maw darted behind the Probe, Burnett pursued directly behind him as Hawes—in a bid to cut off Maw's escape—sprinted in front of the Probe's hood.

Don't Even Think About It

As Burnett rounded the passenger side, Maw's right elbow suddenly popped up high to his side. The unnatural posture raised red flags in Burnett's mind.

Then Maw twisted and spun his upper body towards Burnett, who saw that the con now held the 7.62mm CZ-52 that he'd removed from his waistband. He pointed the gun at the sergeant.

"Don't even think about it, motherf____r!" Maw yelled.

Burnett didn't think about it.

He reacted.

Burnett does not remember pointing his Glock .40 sidearm at Maw. If he spoke, the words are now forgotten. All that he was aware of then and now was the jerking recoil of his pistol as he squeezed off four rounds of Speer Gold Dot ammo at the con.

Maw fell to the ground, landing on his back, the CZ-52 still in his right hand. Maw rolled over on his left side, looking to Burnett as though the man was trying to get up.

Maw raised his right hand and Burnett fired twice more as Hawes came around the front of the car and fired a single shot into Maw's body.

Burnett stared at the downed con, taking note of the incongruous absence of blood. But the telltale lack of breath told him all he needed to know. Maw was dead.

[PAGEBREAK]

Post Mortem

Maw's actions—while self-destructive—were perhaps predictable in retrospect. Facing federal indictment and possible life in prison, Maw knew where his life was headed.

Asked about Maw's desire to close the door, Burnett believes the man was either angling to ditch the gun, or put the car in drive and take off.

"He actually had a baggie of meth in his pocket," Burnett says. "He was probably spun up a little bit, but he wasn't tweaking like a normal methhead bouncing all over the place. He wasn't that bad."

Burnett reflects that his agency's scenario-based range training helped.

"Maybe a month before this, we did our qualification and this kind of scenario was played out in live fire training where we had to quickly draw and fire at close range. It wasn't quite identical, but it was close. We were simulating taking down information and then all of a sudden had to drop it and fire quickly. I absolutely believe my training played a factor in this situation. I was always confident in my close range shooting ability, and the ammo I'm absolutely pleased with. It did its job."

Burnett, like most cops who have been in a shooting, is willing to analyze what went right and what went wrong during the incident.

"When I critiqued myself on this situation, I wish I had called over Turley at an earlier point. I think I gave Billy a lot of time to plan by having him sit in the car. If we had dealt with him sooner, he wouldn't have had an opportunity to plan or go after the gun.

"If I could change things, I would probably have dealt with Billy before dealing with the woman and not given him a chance to formulate a plan," he says. "Maw had a long time to figure out what he was going to do. I really feel like that was what he was doing sitting in his car. He knew especially if he got caught with a gun, that was another federal hit; he would never see the light of day."

In retrospect, Burnett also believes that Maw's reaction to dropping his wallet was a red flag. Maw's physical response to the act was so inordinate as to suggest that the man probably thought that he'd dropped his firearm from his waist.

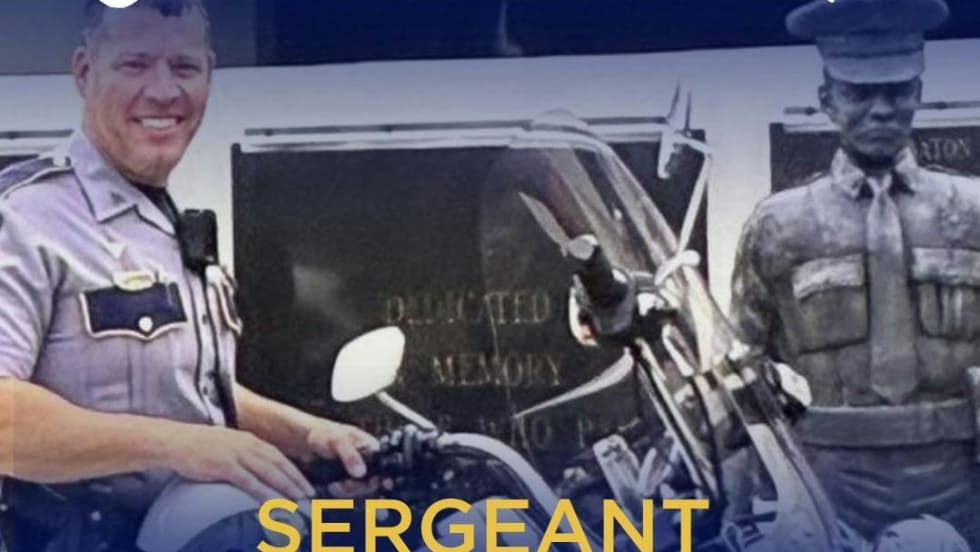

Finally, Burnett has promised himself not to make anymore "rash decisions."

At least, not when it comes to wearing his vest.