Last year—40 years after the creation of SWAT teams—the National Tactical Officers Association (NTOA) established the first-ever national SWAT standards. That's something that many SWAT practitioners and observers consider long overdue.

When SWAT was born in the late 1960s, there were no standards to guide the new concept. The only standards were those established by the SWAT pioneers, namely the Los Angeles Police Department and the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department.

But last year—40 years after the creation of SWAT teams—the National Tactical Officers Association (NTOA) established the first-ever national SWAT standards. That's something that many SWAT practitioners and observers consider long overdue.

A Long Road

Before I go into the NTOA SWAT standards in more detail, an understanding of SWAT history is in order. In the early days, we struggled not only to establish our teams, but also to determine when, where, and how SWAT would be deployed. Even the "SWAT" name was a source of controversy. This was especially true after the "S.W.A.T." TV show, which was popular for two seasons in the 1970s.

Yet, despite these challenges and even vocal opposition from some administrators, the SWAT concept migrated across the nation in the 1970s and really took off in the 1980s. By the 1990s, SWAT had become entrenched as an essential law enforcement component.

While there may not have been nationwide SWAT standards until very recently, individual SWAT teams developed their own strictly enforced high standards. The twin pioneers of SWAT standards were LAPD SWAT and LASD SEB SWT. And many early SWAT teams modeled themselves after these two highly respected teams—who while similar in basic concepts—in fact, were very different from each other.

LAPD and LASD served as role models when it came to SWAT standards. Back then, if you wanted to learn about SWAT, you asked "LA." So, it's no surprise that the nation's premier SWAT organization, the National Tactical Officer's Association (NTOA), was founded by John Kolman, a retired LASD SEB SWT captain.

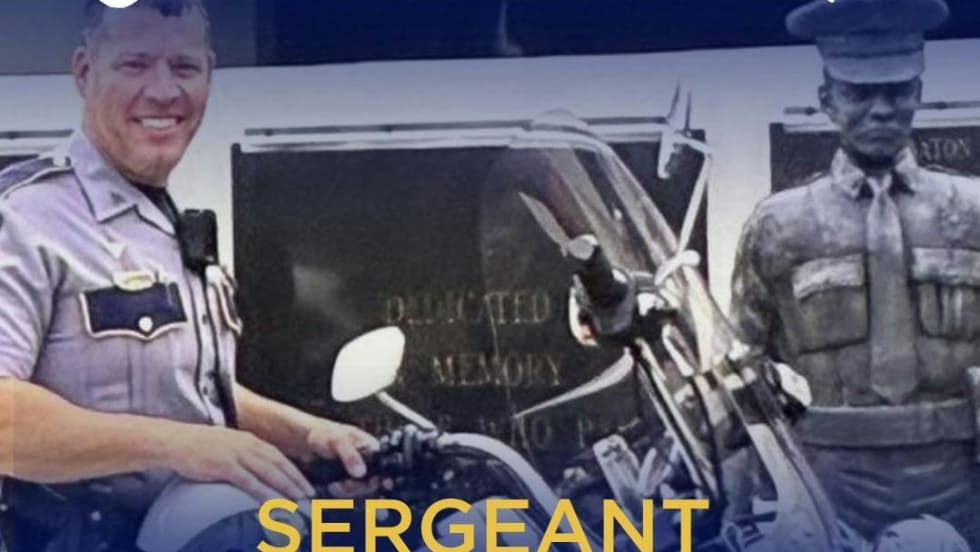

Kolman and other pioneers like Ron McCarthy, a retired LAPD SWAT sergeant, have worked tirelessly to turn the NTOA, which was founded in 1983, into the respected SWAT authority it is today. Early SWAT was influenced by LAPD/LASD, but today NTOA has an even bigger impact on SWAT.

Getting here wasn't easy. For 40 years, SWAT has faced troubles and challenges. Especially in the early years, there was often fierce resistance to SWAT, just as there was with transitioning from revolver to semi-auto or adopting body armor. Law enforcement is traditionally resistant to change, so it's not surprising that even today, there's still resistance to SWAT in some law enforcement agencies.

One prime example was my agency, the Cleveland Police Department. On the CPD we went through five different "tactical" concepts/units from 1970 to 1978, before we were finally allowed to form the current CPD SWAT Unit. That's not conducive to winning, nor maintaining professionalism and teamwork.

[PAGEBREAK]

Standards Needed

A SWAT unit is a team of professionals who are dedicated to the highest standards of excellence, are highly trained, and are capable of dealing with extraordinary threats beyond the capability of other law enforcement. The concept has been proven over four decades by men and women who have to work like hell to make their teams and then work even harder to stay on them. It's a concept that saves lives, not only of officers, but innocent civilians, and even the bad guys.

Yet, today, there are those in law enforcement who still "don't get it," who resist the very concept of SWAT or distort what SWAT is or should be.

Take the example of a midsize Midwest suburban agency whose chief finally relented in the early 1990s and allowed his officers to form a tactical team. He OK'd the team and had it trained by a nearby highly respected, experienced city SWAT team.

This suburban agency's tactical team members were what you'd expect—dedicated professionals, eager to learn, which they did, drinking in every aspect of becoming "tactical." They completed the training with flying colors, and should have been well on their way to becoming a worthy SWAT team.

I say "should have" because the whole thing was a sham. The chief had no intention of letting the team ever deploy. The chief wanted a "paper tiger," a trained tactical team, but one without teeth that he would never allow out of its cage. I can only imagine the disappointment the team members felt when they realized their chief didn't believe in them.

I cite this example because had there been standards in existence at the time, this chief would have been hard-pressed to get away with what he did. Professional standards exist to serve as a guide for excellence in virtually every bona fide profession today. They exist to ensure the highest degree of excellence and consistency throughout these respective professions.

Models to Follow

Professions such as medicine, the military, education, fire fighting, and yes, law enforcement all have specified standards.

Every state in the United States has its own regulatory authority over its law enforcement agencies and officers. This includes SWAT—maybe not specifically, but usually under the wider umbrella of overall state law enforcement standards.

And beyond the standards set by each of the 50 states, select police specialties have established their own sets of national standards. A prime example is the National Bomb Squad Commanders Advisory Board (NBSCAB), established in 1998. NBSCAB developed nationwide guidelines and standards for the bomb squad community at the federal, state, and local levels.

If there is any police specialty unit that closely resembles SWAT, it's the bomb squad. As with SWAT, bomb squad work is hazardous and requires great skill. Explosives are unforgiving and impersonal in their destruction, and very clearly, only the most highly trained, experienced technicians should be allowed anywhere near suspected explosive devices of any kind.

One major difference between bomb squads and SWAT, of course, is that you never hear of any command officer hovering over the shoulder of a bomb tech trying to diffuse a suspected IED. No, during such incidents command and everyone, except the bomb techs, stay as far away from the vicinity as possible. They allow the bomb techs to do their job without unwanted interference or advice. Something I'm sure some in SWAT wish were true for them also.

That bomb squads universally subscribe to NBSCAB standards across the nation is a testament to their profession. Who better to establish guidelines and standards for bomb squads than those most qualified to do so, the bomb techs themselves?

[PAGEBREAK]

Best Practices

Very little has been written about SWAT, beyond the news reporting of SWAT incidents. Until 1997 when Peter Kraska released his controversial, critical report: "Militarizing American Police: The Rise and Normalization of Paramilitary Units."

The NTOA responded to this critique by developing its "Suggested SWAT Best Practices," released around 2001. The "best practices" were not intended as standards, but recommended guidelines for improving professionalism within the SWAT community. And some in the community thought this was all we needed.

Then in 2006, Radley Balko released his controversial, critical CATO Institute white paper report: "Overkill: The Rise of Paramilitary Police Raids in America." As the title indicates, Balko focuses on what he calls "botched raids" by SWAT.

Balko's report was answered in 2007 by Dr. David Klinger, a University of Missouri-St. Louis professor and former officer. In contrast to Kraska and Balko, the goals of Klinger's study, "A Multi-Method Study of Police Special Weapons and Tactics Teams in the United States," were to study SWAT team structure, how SWAT prepares for operations, and SWAT use of force. He found that SWAT is less likely to shoot during critical incidents than non-SWAT officers.

The deadly 9/11 terror attack created the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) to prevent and respond to future terror attacks on America. If 9/11 served as a wake-up call for America, the devastating 2005 Hurricane Katrina, and the unprecedented influx of numerous law enforcement agencies from across the U.S. into the area, proved the need for law enforcement to standardize response in a number of areas, including SWAT.

On the Same Page

Reacting to several controversial SWAT incidents, the attorney general of California published "SWAT Operational Guidelines and Standardized Training Recommendations" in 2005. Based in part on the NTOA's "Suggested Best Practices," these guidelines affected all SWAT teams throughout the state.

Meanwhile, NTOA was working with FEMA rewriting the National Incident Management System (NIMS) for SWAT. Once that was completed, the NTOA leadership decided to tackle the daunting task of creating national standards and guidelines for SWAT.

According to NTOA president John Gnagey, these standards are actually recommended guidelines. Gnagey says the NTOA recognizes the importance of individual teams and their respective agencies and states to retain their individualism.

Unfortunately, the NTOA also realized that the quality of SWAT teams in this country ranges from the fully capable to the marginally capable. So the need to establish minimum capabilities is increasingly apparent.

In SWAT talk, the goal is to get all teams "up to speed" and "on the same page," especially in major incidents involving multiple agencies. This is something that emergency medicine and fire service units have been doing with great success for a number of years.

[PAGEBREAK]

Some Details

So what's in the September 2008 "NTOA SWAT Standards for Law Enforcement Agencies?"

As with most publications of this type, it's a pretty dense document. But the contents include a definition of SWAT, the purpose of SWAT teams, the scope of SWAT standards, team configuration, agency policy, operational planning, and the development of multi-jurisdictional SWAT teams.

NTOA says the objective is to: "Establish SWAT standards to serve as an efficient core set of concepts, principles, and policies to standardize and enhance the delivery of tactical law enforcement services."

Here's a sampling of what's in the NTOA standards:

Minimum Training Standards

Part-time SWAT teams—Prerequisite: 40-hour basic SWAT course. Monthly: 16 hours. Specialty: 8 additional hours; 40 hours in-service annually.

Full-time SWAT teams—Prerequisite: 40-hour basic SWAT course. Monthly: 25 percent of on-duty time.

The NTOA standards include similar detailed guidelines for tactical command, containment, emergency action, deliberate action, and precision long rifle. Other sections of the NTOA standards cover missions, mutual aid, equipment, protocols and SOPs, and after-action reports.

Post-9/11 Thinking

Cleveland SWAT Sgt. Dan Galmarini says he believes one of NTOA's missions is to make SWAT "more credible and professional." And he thinks the new standards are a strong step toward ensuring that "all of SWAT is on the same page."

Galmarini says that in the past two years, Cleveland SWAT has "stepped up training with other teams in the region, including adjacent counties." And he found that the teams have many similarities and differences, but the core principles are comparable and that enabled the "troops to mesh together." Today, Cleveland SWAT is comfortable working with other regional SWAT teams.

Galmarini believes the NTOA standards are all about teamwork. And isn't that what SWAT is about? SWAT teams use teamwork to take on those situations and incidents deemed too dangerous and/or beyond the capabilities of other police. SWAT, by virtue of its design, structure, training, and equipment is better suited to respond to such situations, enhancing the chances for more successful outcomes, with fewer casualties.

The looming threat of terrorism on U.S. soil means that law enforcement must be ready at all times to respond to an attack. A spearhead of counter-terror response is SWAT, and the reality is there are very few individual SWAT/tactical teams capable of dealing successfully with terror attacks, especially multiple simultaneous attacks. So multiple SWAT teams will need to be able to work together on the same page.

Many in SWAT who understand the gravity of these extraordinary threats to society know that having all American SWAT teams on the same page could make a difference in a major incident, and NTOA's recommended SWAT standards are a huge step in the right direction.

"NTOA SWAT Standards for Law Enforcement Agencies" represents the first comprehensive attempt to establish nationwide guidelines for police law enforcement units. If you discover your team isn't up to the standards, the NTOA report will give you ample ammunition to persuade your agencies to get you up to speed.

To learn more about the NTOA SWAT Standards, contact NTOA directly at: ntoa.org or call (800) 279-9127.

Bob O'Brien is a retired Cleveland SWAT officer, chief correspondent for PoliceMag.com's SWAT Channel, and a member of the TREXPOAdvisory Board.