Last month an independent board of inquiry released a report on the incident that killed two Oakland, Calif., SWAT sergeants last March. They were shot by Lovelle Mixon who had earlier that day murdered two Oakland patrol officers during a traffic stop, but the report clearly suggests that these SWAT officers were also killed by poor leadership as much as by Mixon's bullets.

I'm not writing this column to condemn the Oakland brass who were in charge of the Mixon operation. They dealt with a nightmare scenario that required them to make split-second decisions when emotions were running high.

And even the best leaders tend to make disastrous decisions when their blood is up.

Consider Robert E. Lee's catastrophic strategy of attacking the Union center on the third day of the battle of Gettysburg, a slaughter called Pickett's Charge. Lee was by all standards a brilliant military commander, but on that day he asked his men to do the impossible. And they knew it was impossible, but they charged across that field anyway because their leader told them to do it. They would have marched through hell for him.

True leaders inspire that kind of loyalty in their charges. Unfortunately, bad leaders can also get their troops to march through hell because they are granted the authority to force their people to obey their commands.

Sticking with our Civil War discussion, let's look at Ambrose Burnside. By all accounts Union Major General Ambrose Burnside was a good soldier, a brilliant gun designer, and an all around fine human being. But he was also quite possibly the worst commander on either side in the Civil War.

At Antietam Creek, Burnside got his men slaughtered by insisting they cross a bridge under enemy fire even though the creek below was only ankle deep; at Fredericksburg he sent wave after wave of his troops into a frontal assault against a fortified Confederate position; and at Petersburg his poor planning canceled out the brilliance of a scheme to detonate explosives under Confederate lines and break Lee's trench line. Burnside was a textbook example of the Peter Principle: He rose to the level of his incompetence. Historian Bruce Catton wrote: "Burnside repeatedly demonstrated that it had been a military tragedy to give him a rank higher than Colonel."

I use this discussion of Civil War generals to illustrate two things about leadership: Even good leaders make terrible mistakes and, more importantly, nothing is more dangerous to a warrior - whether he is a 19th century infantryman or she is a 21st century patrol officer - than a bad leader.

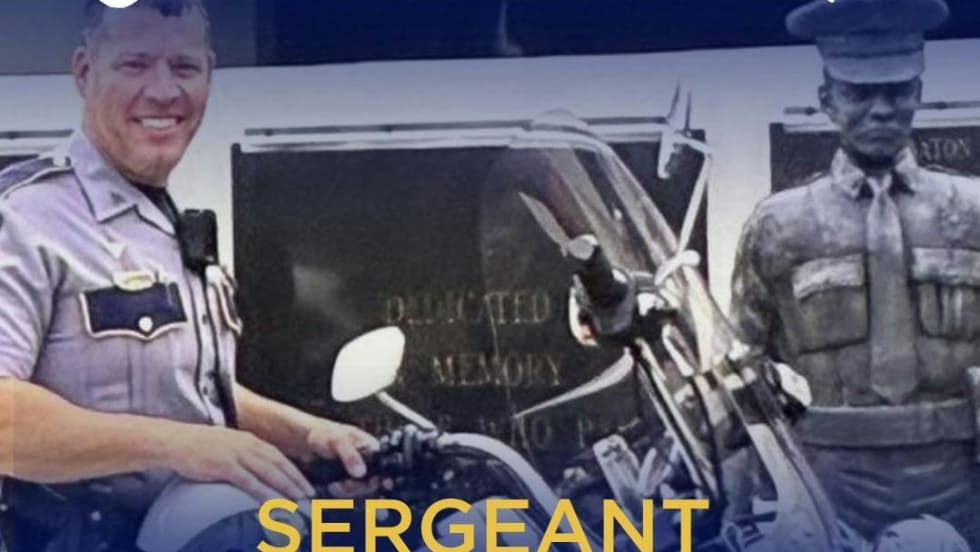

That's why it's critical that only the best warriors get promoted up the ranks in law enforcement. Wearing sergeant's stripes or lieutenant's bars on your police uniform has to be about more than just time served or passing a test; it has to be about effective leadership. Because the truth is that any ranking law enforcement officer may someday have to make the decision to send fellow officers into harm's way.

Unfortunately, some agencies seem to have lost sight of what it means to promote their officers. A promotion should only be given when an officer demonstrates effective leadership and is capable of commanding others in a crisis. To promote someone for any other reason is to make a joke of the command structure.

Officers should not be promoted because they are white or nonwhite, because they are male or female, or because they play golf with the mayor or the chief. And because of my experience serving as a role player and an evaluator in numerous assessment center scenarios, I am absolutely convinced that a written exam should only be one small element of the promotion process. The only valid reason for promoting anyone in law enforcement is that he or she is ready to command and has demonstrated effective and competent leadership.

Stripes and bars are not a reward for perfect attendance. They are symbols of command. And command is a huge responsibility. To treat it as something less endangers every officer unlucky enough to look to that commander for leadership.