I started that morning with a visit to the doctor's office, fully expecting to walk out with a prescription and get on with life. Instead, I ended up in an Intensive Care Unit 90 miles from home.

Honestly, I thought it was just a bad chest cold.

I started that morning with a visit to the doctor's office, fully expecting to walk out with a prescription for some knockout medicine and get on with life. Instead, the next few hours turned into a whirlwind of frenetic activity by an assortment of medical personnel, with me ending up in an Intensive Care Unit 90 miles from home. But let me back up and fill in some of the details.

Something's Wrong

I was finally at home after spending three weeks on the road. The last week or so, I had developed a nagging dry cough. Naturally, my first thought was I was coming down with something. After all, my wife Julie had just gotten over a cold a few weeks before that. She was the one who noticed the next oddity: My heart was trying to pound its way out of my chest. My resting heartbeat was noticeably harder and faster than normal. I jokingly told her it was because I was excited to be home. I wasn't worried because even though I'm no longer on SWAT or in law enforcement, I've made an effort to maintain a high level of physical fitness.

But over the next two days, other more worrisome things started to happen. The cough was getting worse, and several times I found myself breathless and lightheaded when I stopped. The simplest of physical tasks, like walking to the mailbox, also left me struggling to catch my breath. Last, but certainly not least, my right calf had swollen to nearly twice its normal size. With all of this, it was time to go to the doctor.

We were fortunate enough to find a doctor who could get me in within two days. When we met the doctor that morning, we still believed it was going to be something simple. However, the expression on the doctor's face was less than comforting. Right there, he made a phone call to a colleague-a specialist-and we listened as he told him I needed to be seen right away.

Medical Mystery Tour

Our next stop was the office of that cardiologist. He conducted an EKG, checked my leg, asked a few questions, and then started scribbling frantically on some official-looking form. Finally, he gave me the news.

He believed I had a blood clot in my leg, and it appeared that it may be breaking up and sending additional clots into my lungs. The only way to know for sure was with the additional tests he was ordering, to be done immediately in the emergency room. Off we went to the next stop on the Medical Mystery Tour.

I walked into the emergency room about 15 minutes later. I handed the nice lady at the desk the paperwork I'd been given. Next thing I know, I'm being assisted into a wheelchair and hustled down a hallway to the heart of the ER. Quickly I was transformed into a patient: gown, gurney, oxygen and monitors, tests and more tests, all in rapid succession. Then lots of questions: Are you having chest pain? Have you been coughing up blood? Do you need oxygen? No, no, and no.[PAGEBREAK]The Diagnosis

Finally, the diagnosis from a grim-faced resident came. I had a major blood clot behind my right knee, most likely a deep vein thrombosis (DVT). It definitely was sending multiple pieces through my heart and into both lungs, where they were lodging in the smaller blood vessels. As a result, my lung capacity had been cut to 25 percent of normal.

In a separate but medically unrelated attempt on my life, the pericardial sac around my heart was filling with excess fluid. Being crowded by the fluid, my heart could not beat properly. To compensate, it was beating harder and faster than normal. In fact, my resting pulse was over 110 beats per minute. I had been effectively running a marathon for days.

This information was the final confirmation the medical staff needed to go into crisis mode. My wife and I had lots of questions, but no one wanted to give us clear answers, always telling us to talk to someone else.

I was told I was in dire straits, and despite my protests I was going to be transported to another hospital, one that was specially equipped for this type of case. They felt that if (or perhaps when) something catastrophic happened overnight, their hospital didn't have the staff to properly deal with it. So, my journey continued, as I was packed up for an ambulance trip across the state. I kissed Julie goodnight, and off we went.

Not Supposed to Be Alive

Ninety minutes later, I was in another emergency room, with more medical staff buzzing around me. More monitors, more tubes, and more looks of grave concern. My journey that night ended with me in the Intensive Care Unit, complete with a personal nursing staff. As things settled down, I was finally able to get a senior nurse to sit and talk with me about what was going on, and why everyone had been so frantic to this point.

She gravely told me that I was not supposed to be alive. With my condition, I should have been coughing up blood, in considerable pain, and my blood pressure should have been crashing. My heart should have given out from the added stress.

People in my condition don't just walk into the ER. They are transported by EMS, usually clinging to life by a thread. Instead, I was calm, coherent, and physically holding my own. I was breathing without supplemental oxygen, my oxygen saturation level was at 95 percent, and my blood pressure was normal.

At this point, the doctors were a bit confused. Perhaps that explains the seemingly endless parade of doctors, nurses, and specialists who visited my bedside during my three days in ICU. They all had lots of questions, but only one, my new cardiologist, actually had an answer.

Among others were multiple questions about my lifestyle: Do you smoke, drink, take any medications? Do you exercise regularly? What do you do? I told them I was a retired SWAT officer who still maintained an intense exercise regimen.

Most of the patients coming into the ER with double pulmonary embolisms are often older, overweight, smokers, and/or out of shape, I was told. I had none of those things working against me, but most importantly in my cardiologist's eyes was the fact that I was in very good shape. That allowed my lungs to immediately start to compensate for the loss of capacity, and for my heart to handle the strain it had been put under for so long.

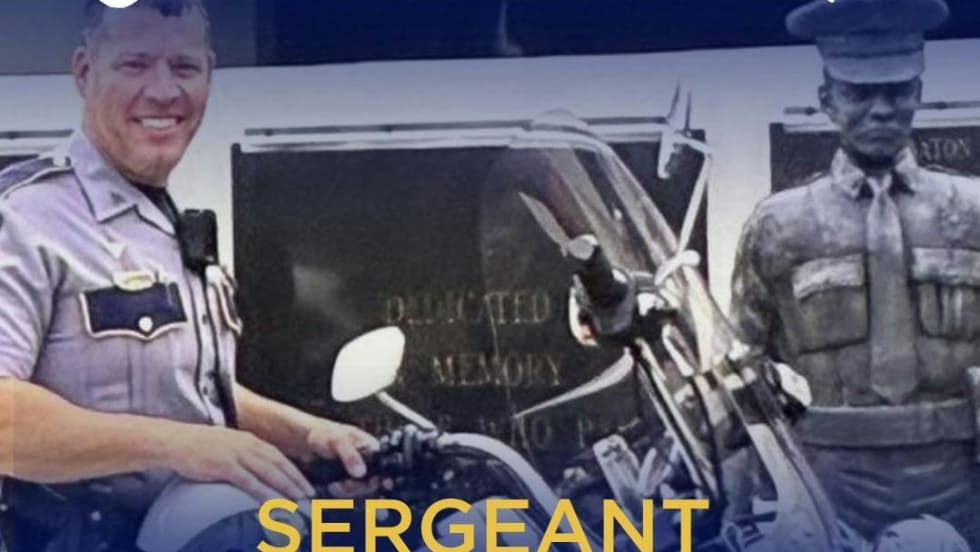

The bottom line? My being in good physical condition had saved my life. Years of workouts had paid an unexpected dividend. P.O. Wenger would be proud.

A Lifelong Commitment

I started the police academy 30 years ago, and early on I learned a valuable lesson, one that would stay with me for life. The first day of the academy, we were introduced to many of our instructors, one of whom was to be our physical fitness instructor. He was an imposing man with a strong command presence and a physique cut from stone. His first words from the podium still ring in my head: "When you decided to become a cop, you lost the right to be out of shape."

For the next 10 weeks, we started every single morning with a full hour of intense PT and DT sessions. Upon graduation, I was in the best shape of my life. But more importantly, I left with an appreciation of why I had to maintain this new physical discipline.

I believed that every day, people were counting on me to be able to do my job. Most days, that was as mundane as driving a car and pushing a pencil. Some days, however, that may entail running down some bad guy, or fighting for my life, or my partner's. I had an obligation to be in condition to do that.

When I joined SWAT, the discipline carried over as the responsibility grew. Now, a whole team was counting on me to be able to carry my weight and do my job, whatever that may be.

So, every day throughout my career, I made a commitment to live right and do the work to stay in shape, or be willing to give up the position. I was no gym rat, but my lifestyle incorporated time to run, cycle, lift weights, and do CrossFit routines.

When I retired, there was no longer a career-driven reason to continue to push myself. In fact, in the months leading up to my last day at work, I often blissfully entertained the thought that I could finally stop running, and could cut back on the gym time. But my life didn't end with my time behind a badge.

I have heard the statistics about the high mortality rates for retired cops. After working all of those years, my family deserved a high quality of life from me beyond retirement, and I was not going to shortchange them. So the workouts continued, and my personal fitness standards remained the same. In the end, the time, sweat, and sacrifice paid off.

Back at It

I won't bore you with the details of the rest of my two weeks in the hospital. Let's just say it's an adventure I don't want to repeat, ever. Although, I have one story I want to share in a moment.

The heart issue turned out to be a viral infection that had nothing to do with the clotting problem. The clots and the infection were aggressively treated, and I was finally well enough to go home. When the doctor said I was going to be discharged, I had two questions for him: When can I go back to traveling and teaching, and when can I go back to working out? He cleared me to do both right away. Good, because I had work to do. I was on the bike the next day.

Dr. Doom

My attending pulmonary specialist in the hospital earned the nickname "Doctor Doom" because he seemed to always be the harbinger of bad news and worst case scenarios. During his daily visits, he almost appeared disappointed that I was not wheezing and withering away. He knew about my fitness routine, and also credited it with my survival.

However, he was quick to assure me that I would never be able to run four miles again. "You may be able to run a mile someday, but you won't be able to run four miles. You probably have too much damage." Those words burned in my ears for the duration of my hospital stay. And they drove me through every daily workout I did after getting home.

I probably pushed harder than I should have, but six weeks later, the day before my first follow-up visit with Dr. Doom, I ran my four-mile course, and felt just fine. I made a point of telling him that the next day.

Sweat Equity

So, why do we work out? The reasons for maintaining a fit lifestyle are simple and redundant. As a police officer, being in good shape will enable you to do your job safely and effectively. As a SWAT officer and a sniper, being in good shape will enable you to do your job safely and effectively. For those of you lucky enough to reach retirement, being and remaining in good shape will enable you to enjoy a higher quality of life, for a lot longer. And after all, isn't that why you worked all of those years? For this, your family and friends will thank you.

Find a reason to motivate yourself, and make a commitment to do the work necessary to stay alive and to live well. The look on Julie's face when I was discharged was worth every rep, every mile, and every drop of sweat.

And of course, you'll also still look good naked.

Derrick Bartlett is a former Fort Lauderdale (Fla.) PD SWAT team member and sniper who now trains police officers in firearms and SWAT tactics and serves as director of Snipercraft.