Law enforcement, like much of American society, is still trying to come to terms with all the events and innovations of the last 17 years. And perhaps no other aspect of law enforcement has seen more change since the dawn of this century than SWAT.

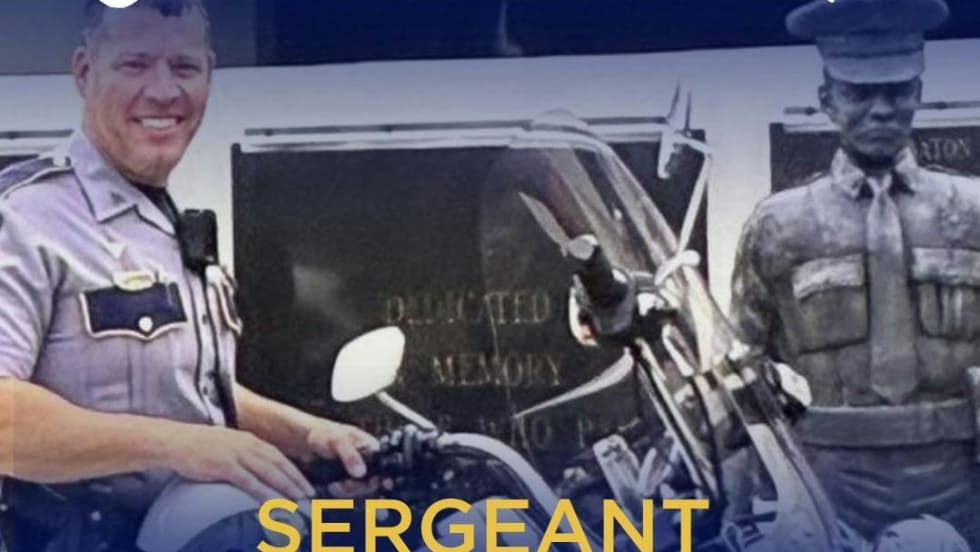

Lt. Joe Dietrich of the Maricopa County (AZ) Sheriff's Office (MCSO) has been a witness and a participant in the last two decades of SWAT evolution. Dietrich began his tactical law enforcement career in 2001 and has spent nine years on the MCSO team, rising from deputy to sergeant. (Now that he is a lieutenant, he's been reassigned, but he wants to go back.) "There were a lot of changes on the team from the first time I was on it to when I was a sergeant and even in the last two years," he says.