What's keeping law enforcement's unmanned aircraft on the ground is a combination of convoluted regulations and the public's belief that allowing officers to use these little aircraft will violate their civil rights and invade their privacy.

Law enforcement agencies could use unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) to search for suspects, obtain intel for critical incidents, and survey disaster areas without the use of a helicopter or plane. This could provide cost savings and keep pilots out of harm's way. But almost as interesting as their uses is why many agencies aren't taking advantage of this technology.

What's keeping law enforcement's unmanned aircraft on the ground is a combination of convoluted regulations and the public's belief that allowing officers to use these little aircraft will violate their civil rights and invade their privacy.

What is a UAS?

An unmanned aircraft system (UAS) flies using an autopilot system that assists the pilot when flying the aircraft manually, or has the ability to fly the aircraft by itself using a pre-loaded flight plan designed by the pilot for that specific mission. There are helicopter and fixed-wing plane versions available in a range of sizes, prices, and levels of sophistication. Retail models sell for as low as $1,000, while higher end UAS can cost $50,000 and up to hundreds of thousands of dollars. Affixed cameras capture video and still images and provide live feedback to the crew operating the device from the ground.

Activist groups rail against law enforcement use of aerial cameras claiming invasion of privacy. Yet the FAA's strict regulations severely limit where agencies can use UAS beyond the already established guidelines for manned aircraft. And any video or still images related to an investigation must be treated as evidence, for which every agency has strict policies.

Additionally, public outcry about the "militarization of police" has fueled people's imaginations to such a degree that more than a few mistakenly believe police officers are poised to use military Predator drones complete with ready-to-launch missiles. The widespread use of the term "drone" to describe all unmanned aircraft helps perpetuate this myth.

"We call ours unmanned aircraft," says Ben Miller of the Mesa County (Colo.) Sheriff's Office. "We try to be as informative as we can, and we feel, although the common name is drone, that doesn't explain what we do. We're not operating a Predator with Hellfire missiles. We operate small unmanned aircraft."

This idea that unmanned aircraft systems (UAS) are the same as what the military uses couldn't be further from the truth. No U.S. law enforcement department wants to bomb the public. Police UAS are only armed with cameras. Besides, in reality, it would be almost impossible for a police department in the United States to afford the type of unmanned aircraft the military operates, let alone get approval from the Federal Aviation Administration to use it in any capacity.

Public Sentiment

Los Angeles is a prime example of how people's fear of police surveillance can stymie law enforcement's efforts. Both the LAPD and the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Office have had to ground unmanned aircraft because of citizens' privacy concerns. Just last month the Los Angeles Police Commission announced it would hold six months of public hearings before determining how or if its two Draganflyer X6 UAS would be used. During that time the LAPD's Inspector General has them under his care. The LAPD received these UAS from the Seattle Police Department, which had obtained them with a federal grant but got rid of them due to privacy concerns.

"They are a tool of good, not a tool of evil," says Police Foundation President Jim Bueermann. Convincing many citizens of this statement is one of the main goals of the Unmanned Aircraft System guide from the Police Foundation. It's scheduled to be released this month and is being funded by the U.S. Department of Justice Office of Community Oriented Policing Services.

The guide is intended to help law enforcement agencies understand potential costs and benefits of using UAS, legal challenges and liability issues, impact on privacy, and the collection and use of UAS-acquired data. It is also intended to provide guidelines for deploying UAS in policing scenarios in accordance with the Fourth Amendment, civil liberties, and community policing philosophy.

"You can't use a UAV in a community without expecting criticism if people don't understand why you're using it, and are not convinced of your commitment to transparency," says Bueermann. "This applies equally to UAVs and SWAT vehicles."

For this reason, the Grand Forks (N.D.) Police Department has welcomed citizen participation in its UAS program from the get-go. Members of the public and the media sit on the UAS Compliance Committee that determines when to allow UAS use in their area, based on its FAA certificate of authorization or COA. It's a joint effort among Grand Forks PD, the local sheriff's department, and the University of North Dakota, which established the program as a research project.

"You have to know your community's acceptable standard," advises Capt. Mark Nelson, Grand Forks PD operations division commander. "Whether you have a National Night Out event or career fair, don't be afraid to put the items on display. People are afraid of what they don't know."

The committee plans to soon provide training and education packages to all counties of North Dakota. "We have less population, so it's easier to reach out," Nelson acknowledges. "But people are also more ultraconservative, so we've bridged that gap by bringing out a public info campaign early and letting them know what it's about."

FAA Challenges

The Federal Aviation Administration has the authority over approval for public agencies to operate UAS. Each agency must submit an application to obtain a COA. This details specific guidelines for when, where, and how UAS can be used, and it's different for every agency. This makes the FAA's system very difficult to navigate.

"We obtained [UAS] in 2009, and we trained and worked with the FAA until 2011. In the summer of 2011 we finally got our certification of authorization to fly them," says Lt. Aviel Sanchez, who heads up the Miami-Dade Police aviation unit. "In theory, it's a great program, but the practicality is limited."

That's because the restrictions for how UAS may be operated even with a COA are so extreme. For Miami-Dade PD, they must notify the FAA within one hour of deploying or while en route to an emergency, the UAS must be operated by certified pilots and always within the line of sight of a pilot, and it must fly within 300 feet in altitude, Sanchez says. And these are just a few of the restrictions.

One requirement that comes up most often for agencies is the "line of sight" rule. An operator on the ground must be able to see the UAS to operate it. If he no longer has it in view because of trees or buildings in the way, or because it's just too far away, the entire crew must land the UAS, move their set-up to a different location, and launch the aircraft again in the new area. This makes using UAS for search and rescue prohibitive.

New guidelines for how public agencies can gain FAA authorization to operate UAS should be available by September 2015, which experts hope will provide clearer guidelines for authorization and fewer restrictions to use.

"I think the rules requiring line of sight to operate unmanned aircraft will change, but I don’t think that will change by 2015," predicts Miller. "I think you will see a process better than a COA process, with blanket rules instead of on a case-by-case basis."

Current Operations

Right now, the few agencies with COAs to operate UAS use them for very specific missions. For the Grand Forks (N.D.) Police Department this is limited to crime and traffic accident scene analysis, disaster scene assessment, missing person search, suspect search, major event vehicle traffic pattern monitoring, and crime scene documentation.

The one time the Miami-Dade Police Department set up its UAS for actual deployment, it was to be used in a barricade situation to provide intel for the tactical team without putting any personnel in harm's way. Fortunately, hostage negotiators were able to resolve the incident before the UAS was needed.

"We only use UAS for something ongoing or that has already happened. We don’t fly over an area to find a drug grow operation," explains Grand forks PD's Nelson. "We know what court rulings have stated, and we will work within what the courts allow us to do."

According to Dan Schwarzbach, executive director and CEO of the Airborne Law Enforcement Association (ALEA), if given the chance, UAS can do the same things as helicopters or planes, or even better.

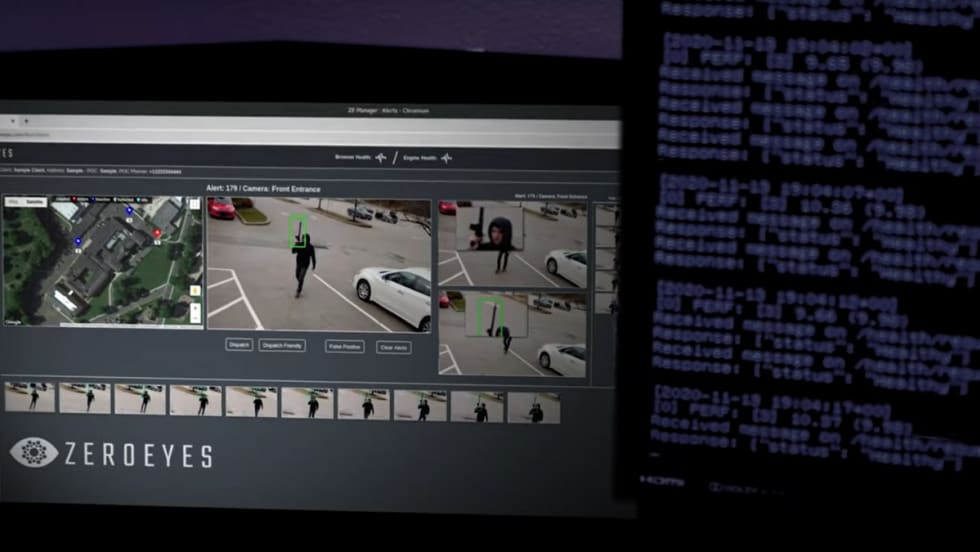

"Say there's a shooter at a school and you want to get situational awareness on where he is. Get a small vertical lift UAS," he suggests. "It fits in the back of a car, you can launch it fairly quickly, and you can get it at 400 feet, rather than call in a manned helicopter at much greater expense. And while you can't put a helicopter in a school building looking up and down the halls for the shooter, you can do it with a UAS."

And when it comes to documenting crime scenes, a UAS can fly very close to the ground and obtain extremely high-resolution images without disturbing any evidence, unlike a helicopter. Many small agencies that can't afford a helicopter or airplane but could benefit from an aerial perspective for various missions could meet those needs with unmanned aircraft, adds Schwarzbach.

Future Flight

"I think someday, right around the corner maybe, this technology will be ubiquitous," predicts Bueermann. "I can envision a day when every officer uses one, and the notion of contact and cover is different. If you're contact, you're running the UAS, and your partner is running cover inside, behind the UAS. I think this will happen within five years once the FAA removes obstacles to using drones, which should happen in 2015."

For now, many agencies effectively have their hands tied waiting for the FAA's 2015 deadline to determine new requirements for unmanned aircraft use. But in the meantime, you can research the types of products that will meet your needs and start a community awareness campaign to explain exactly how you would like to use these tools, including protecting the safety of police officers and the public. Then by the time there's a clear path to follow you'll be ready to obtain FAA approval with the support of the citizens in your jurisdiction.