Predictive policing is the computerized analysis of historical crime data from databases, record management systems, and other digital sources. Agencies have achieved a lot of great results using this tool, but experts say law enforcement agencies have just begun to scratch the surface of what the technology can do.

Crime prevention has always been to some extent about prediction. Law enforcement officers know by experience and by their street sense they can expect certain types of crimes in certain areas of their jurisdictions at certain times. For example, it doesn't take the world's greatest crime analyst to predict that auto burglaries will soar in shopping malls during the Christmas season or that muggings will increase in working class neighborhoods around payday.

But over the last five or so years the predictive capabilities of law enforcement agencies have become much more sophisticated as analytical computer software has been applied to forecasting where and when crimes are likely to occur. The result is predictive policing, a science that many expect to revolutionize crime fighting.

Predictive policing is the computerized analysis of historical crime data from databases, record management systems, and other digital sources. Agencies have achieved a lot of great results using this tool, but experts say law enforcement agencies have just begun to scratch the surface of what the technology can do.

Beyond Forecasting

"Police officers who work in a community generally know the top five or six spots in the community that will regularly be hot spots," says Larry Samuels, CEO of PredPol. "Computers can predict the top 20 hot spots in the community where crime is likely to occur and do it not just across the board but by specific crime types and time of day."

According to Cynthia Fay, sales manager for crime prevention and prediction for IBM's SPSS Modeler predictive tool, law enforcement agencies that contact her about acquiring the software are interested in transitioning their posture from reactive to proactive.

"We're not trying to replace the officer's gut feeling," says Fay. "We're trying to enhance it with predictive policing. We know you know the areas where you need to patrol, but do you know the precise street you need to be on? Well, we can tell you."

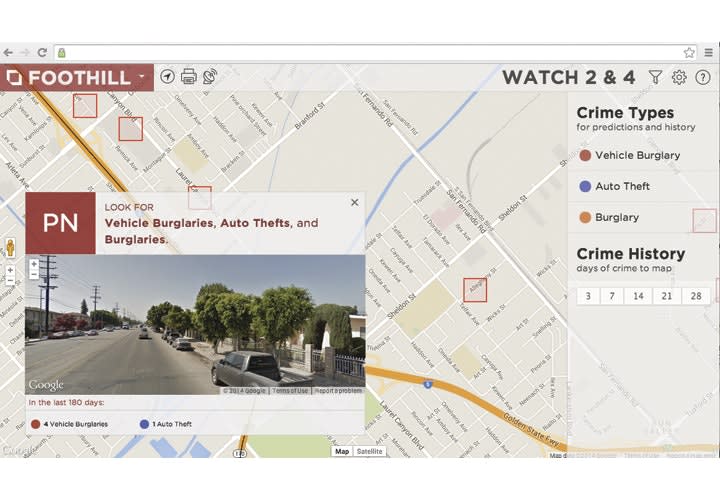

Predictive Policing tools can also identify where crimes are likely to occur much more precisely than human analysts, says D.J. Seals of Public Engines (Motorola Solutions). Seals, who served as a detective and crime analyst with an Atlanta-area agency, says there is a big difference between predicting where crimes will occur and using data to forecast trends and identify hot spots. "Wide forecasts are not very helpful because they are not very tactical," he says. "What we do with prediction is that we can analyze long-term patterns of specific crime, say auto theft, in specific ways and go back many years. Then we can run those algorithms until the data gets closer to the crimes that are currently occurring. Our CommandCentral then reveals these very small and tactically effective boxes [where that specific crime is likely to occur]. In contrast, hot spotting by human analysts can give you areas that are miles long. You can't really respond to a mile-long hotspot very effectively."

Seals says the boxes identified by CommandCentral provide agencies with a variety of information that is tactical and actionable. "It takes into account crime type, time of day, and the temporal shift of the criminal activity as it moves around during the day. It also takes into account seasonality such as when the kids are out of school or the holidays are coming up and crime increases."

Achieving Results

Using predictive policing data, agencies have achieved remarkable results. For example when the Atlanta Police Department deployed PredPol in two of its six districts, officers responding to the predictions achieved a 10% drop in crime in those areas in just 90 days. When the technology was deployed citywide, crime dropped 19%, Samuels says.

Other software platforms have yielded similar results. In one year of using Public Engines' CommandCentral, the Covington (Ga.) Police Department achieved a nearly 20% drop in FBI Part 1 crimes. Lancaster, Calif., an IBM SPSS Modeler user, saw a 35% decrease in the crime rate vs. its benchmark rate set in 2007 after it implemented predictive policing.

Det. John Rivera of the Rosenberg (Texas) Police Department in Rosenberg, Texas—a pilot site for Spillman Technologies' new Spillman Analytics—says the agency has used the software to more accurately determine crime hot spots and the times of the day crimes are more likely to occur.

"Before, we were just plotting the locations of burglaries and thefts on Google Maps and the man hours that used to go into that are gone," says Rivera. "It's a good tool. We were trying to do something similar, but that would take hours out of every detective's day."

Seals says the key to achieving results with predictive policing tools is not just getting the information from the software but getting it to the officers in the field who can act on it. "When you have the analyst from on high handing down stuff to the officers there is a disconnect," he says. "The analyst isn't out there in the field affecting crime. So what we at Public Engines wanted to do with CommandCentral was make a fantastic tool for the analyst but also one that can send the information out to the officers on the road."

The information from many predictive policing tools can now be accessed by patrol officers on portable computers, tablets, and even smartphones. Public Engines CommandCentral also lets officers in the field see not only the predictive analysis but also notes about what other officers have witnessed in the target area and a list of the latest crimes in that "box." For example, an officer's notes might have mentioned a specific vehicle that was seen shortly before an auto theft. Later when an officer is patrolling a predicted auto theft site and sees that vehicle, he or she can refer back to the notes and determine whether to make an investigative stop.

Cost and Infrastructure

One of the most surprising aspects of predictive policing is that it is not as costly in personnel resources, infrastructure, and money as some law enforcement executives would expect. Yes, users can spend millions adding this capability to their agencies, and some larger agencies have done so, but most predictive policing software is scalable, and the basic requirements for producing predictive policing analysis are already present in many American law enforcement agencies. All it takes is a digital database or digital databases for the software to analyze, the software, a desktop or laptop computer to run the software, and somebody who has been trained to use it.

Cost of the software can be very reasonable. Most predictive policing software developers supply their products on a subscription model based on the number of users, and they even offer single-user licenses for smaller agencies. PredPol will even do the analysis for its customers and does so for some smaller agencies.

Also, some smaller agencies gain the benefits of prediction without bearing the full cost through agreements with their county sheriffs' offices. Other agencies team up to share the costs. "We can set up multiple agencies on the same CommandCentral system," says Seals. "They're generally blown away by that because they've been told that if you are on a different records system than another agency, then there's no way you can work together on analytics software. We can put them all together and with predictive capabilities so that it really becomes a powerful tool for them."

PredPol's Samuels says agencies should also consider the benefits and the return on investment when weighing the cost. He believes predictive policing technology is a force multiplier that helps law enforcement agencies cope with personnel shortages. "By placing your officers in the right place at the right time, you will reduce crime in your community. You will also save considerable sums of money, as you will be able to return significant amounts of officer time that would be spent writing crime reports back in to the community and that, too, will perpetuate crime decreases."

Finding New Applications

Experts say law enforcement agencies are finding a variety of new and innovative applications for analytics software and data mining that can help them more effectively perform their missions. Some agencies are starting to expand their use of predictive policing tools beyond crime prevention.

The Tennessee Highway Patrol (THP) is now using IBM's SPSS Modeler to predict where accidents will happen. "Traditionally, highway patrols and state police are reactive, not proactive. When an accident occurred, they provided rapid response," says Fay. "The THP used SPSS Modeler to look at their data on where accidents were occurring, what time of day, and under what conditions. We put that information into our data mining bench, and it spit out a prediction as to where they needed to go and at what time down to the hour."

One of the predictions that the THP project revealed is that accidents happen in different places based on the weather. "If it's nice and sunny, the THP needs to send its officers to one place and when a thunderstorm rolls through they need to be sent to another," says Fay.

Another innovative use of IBM's SPSS Modeler predictive technology is in law enforcement hiring. Fay says one of the product's law enforcement users is employing the software to identify bad cops before they are even hired. The agency compares profiles of potential new recruits to those of officers who have "gone rogue" in the past. The agency then has a better idea of problems it might have with that recruit in the future. "If this guy's background looks like this guy's background, the probability that he is going to go rogue is pretty damn good," Fay says.

The use of analytics to identify where crimes will occur and when may remind some people of the future depicted in the 2002 Tom Cruise movie "Minority Report" where people are arrested even before they commit crimes. But industry leaders bristle at the comparison.

"We are focused on preventing crime," says PredPol's Samuels. "All we use in our analysis is the what, the where, and the when. We are constitutionally friendly and very, very accurate."

Samuels says one of the greatest misconceptions about predictive policing is that the technology is about arresting the bad guy. He says there's always the potential for officers to find a perp in the act in one of the hot spots identified by PredPol or one of its competitors but that's secondary to the true value of the technology, which is in stopping crimes before they happen. "The vast majority of property crime is opportunistic. If you reduce the number of opportunities, you can reduce crime. When you reduce crime, you can start to change the mindset of the community. That has its own power in terms of engagement between the community and officers."

For More Information:

ESRI

IBM