In nicer weather, it would have been difficult not to notice the Plymouth Voyager parked on the center median of the interstate. But the sight of a disabled vehicle on rain-slickened Interstate 81 had in recent days become an increasingly familiar one, even if this particular van was canted with two flat tires. In fact, the Virginia state trooper who came across it was already en route to still another accident further down the road.

Nonetheless, he stopped long enough to advise the stranded motorist that he would call for a tow truck. The motorist nodded his appreciation and the state trooper took off, blissfully unaware of the events that had just been set in motion.

James Pridemore, a service manager at the Lee High auto garage, took the call from state trooper dispatch. Arriving at the interstate median a short time later, Pridemore greeted the van’s driver in his usual affable manner. Most people appreciated the overture. But all Pridemore got from the man was an order.

“You’re going to get me out of here,” the stranger declared. “And you’re going to do it, right now!”

The nervous determination in the man’s voice left no doubt in Pridemore’s mind that it would be in his best interests to comply, so the mechanic wasted no time getting the van hooked up.

Getting back behind the wheel of his wrecker, Pridemore found the stranger with the dour expression hopping into the passenger seat. As he put the tow truck in gear, Pridemore couldn’t help but notice the barely contained anger of his sullen passenger any more than he could ignore the shotgun the man had cradled in his lap.

Taking the Call

The ringing of the telephone around eleven o’clock that morning startled Officer Marty Alford. He’d grown accustomed to the yuletide quiet that had settled about the Wytheville police station.

Alford answered, and Lee High Garage mechanic Danny Dalton quickly cut to the point: His co-worker, James Pridemore, was at that moment entertaining a nervous stranger at the garage, a man armed with a shotgun.

Neither Pridemore nor Dalton was in the habit of reporting every stranger who wandered into town, so their concern immediately became Alford’s. Unfortunately, Dalton didn’t have much more information about the man.

Solving the mystery of why an armed stranger with New York plates would be stranded in Wytheville required a game plan. Alford decided he would visit the garage on the pretext of looking over some business insurance papers. Dalton would make sure that Pridemore understood that it was up to Alford to decide when and where he would announce his true investigative intentions.

Alford informed a Wytheville field sergeant who had a recruit ridealong and a narco K-9 from the sheriff’s department of the situation and asked them to back him up. The other officers agreed to park around the corner from the garage and wait for Alford to advise when they were needed.

Alford threw a dress coat over his shirt and tie and headed for an unmarked car. He hardly gave a second thought about putting on his bulletproof vest. It didn’t seem practical. For one, its presence would have been easy to spot and would have dimed off the true nature of his mission.

Fellow Traveler

Pridemore was just putting the replacement tires on the van when Alford arrived at the station. He paused for a second to size up the tactical situation. The mechanics had isolated the van in an area of the garage away from pedestrian traffic. That was really smart and Alford appreciated it. He would have been even more appreciative if he’d known that Pridemore and Dalton had taken the opportunity to surreptitiously remove the shotgun shells from the van while they were working around it.

Shortly after entering the garage, Alford found the stranded man pacing inside. Alford effected the air of a fellow stranded traveler and engaged the man in a few minutes of chitchat. For his part, the man hesitantly volunteered that he was headed for Louisiana. To Alford, it was obvious that the stranger’s mind was already elsewhere.

After a few minutes, the man stepped out to use the restroom. That took him safely away from the shotgun and whatever else might be in the van. Alford decided that the time had come for him to confront the van’s driver.

When the stranger exited the men’s room, Alford identified himself as a plainclothes officer. He escorted the man back to the garage and sat him in the patrol car. There, as his questions of the man grew more probative, he ran a check on the Plymouth Voyager and its driver.

The stranger had initially appeared ill at ease, but Alford’s identification of himself as an officer proved to be an instant ice breaker. Suddenly the man was downright sociable, readily identifying himself as John James O’Connor and explaining that he was making a courier run to Biloxi. To underscore the validity of his contentions, O’Connor presented a New York State security guard identification card.

Back Story

Alford’s own anxieties lessened. Any anticipated altercation had not occurred; if anything, the man seemed to be extremely warm and cordial. All the same, Alford couldn’t help but note that something didn’t add up: The change in O’Connor’s travel itinerary was baffling.

That contradiction was far less important than the back story that O’Connor had consciously glossed over.

O’Connor had failed to mention that his employment had been recently terminated. In the days preceding his arrival in Wytheville, O’Connor had, in fact, worked for Northway Security, a private firm hired to provide unarmed security for some of New York’s off-site betting establishments. But the state had recently decided to discontinue its arrangement with Northway, a decision that precipitated the firm’s dissolution. Among the collateral casualties were the firm’s employees, including John James

O’Connor.

But unlike many of his fellow employees, O’Connor wasn’t one to take the firing sitting down. Things had been going steadily downhill for O’Connor on the domestic front, his holidays were ruined, and, even if he was going to be out of a job by the end of December, he sure wasn’t going to be out of money.

Such were the reasons that factored into O’Connor’s arrival at the off-site betting parlor the previous Friday night when he confronted a clerk with a shotgun. When he walked out a few minutes later, O’Connor was one job poorer and $25,000 richer.

Probable Cause

Examining the shotgun, Alford noticed that the barrel of the weapon had been sawed off, a modification that put the weapon well below the legal limit. The K-9 officer’s dog checked the van; he immediately alerted on some marijuana residue on a box in the passenger compartment area.

Between the sawed-off shotgun and the K-9’s findings, Alford knew that he had more than enough probable cause to conduct a more thorough search of the vehicle. But he also knew that there was more to this man’s story than he was telling, and more than met the eye as far as the van.

Just then, a burglar alarm call went out. As things were quiet and O’Connor was cooperative, Alford felt comfortable letting the K-9 deputy and his sergeant roll to handle it. The sergeant’s 20-year-old ridealong, Dewey Clemons, was left behind to keep Alford company.

Having known Clemons all his life, Alford knew Clemons was not your average ridealong. True, the young man was burdened with a slender build that still made people think of him as a kid. But Dewey Clemons also possessed a maturity beyond his years. And as a pre-academy employee of the Wytheville Department, he possessed something else, too: a department-issued sidearm.

Something for You

As warrant checks for both the New Yorker and his vehicle proved negative, Alford allowed O’Connor to exit his patrol car. O’Connor took a position near the passenger side rear of the van as Clemons stood off to the side, keeping a respectful vigil on the two men. Alford, situated near the front of the Voyager, advised the unrestrained O’Connor of his concerns.

“Are you going to get a search warrant?” O’Connor asked.

“Probably,” replied Alford.

“Oh, yeah?” O’Connor said. “Well then, I have something else for you, too!”

With that, O’Connor’s hand suddenly reached inside the open doors of the van and disappeared into a hole that had been fashioned into a roll of carpeting. When it reemerged it was holding a semi-automatic rifle.

The first round caught Alford dead center. He felt as though someone had taken a red-hot poker and driven it straight through his chest. His legs failed him, and he slid to the cold concrete floor.

Alford’s breathing became instantaneously laborious, nearly as difficult as fathoming just how quickly the situation had so violently changed. Above him, the once peaceful eyes of O’Connor now radiated concentrated hatred as he angled the barrel of his gun down toward Alford’s face.

O’Connor’s finger squeezed violently against the trigger. But…nothing happened.

A misfire? Had the safety somehow become engaged? Alford thought.

It didn’t matter. All Alford knew for certain was that he had to do something to save himself.

The Ridealong

The ridealong recruit Dewey Clemons saw O’Connor shoot Alford. He now saw O’Connor standing over Alford preparing to make a headshot. Nothing he had been exposed to growing up in Wytheville could have prepared him for this moment. Much of what he knew of law enforcement had been acquired vicariously through the injured man before him. Indeed, in Martin Alford he had found one of his most imposing role models—his ideal of the consummate police officer—quiet, compassionate, but quite capable of packing his mud.

The sight of this larger-than-life man taking a round likewise knocked the air out of Clemons. But the recruit was not about to let himself be frozen with fear. He took cover behind a standing tool box and drew his weapon. Eternities passed in measured milliseconds as Clemons angled for a shot that wouldn’t put Alford in added jeopardy.

Death Grip

Alford was fighting a battle on two fronts. While his mind fought the pain, he took the fight to O’Connor. The pain seemed to abate and adrenaline flowed into his system. His left hand shot up and acquired a death grip on O’Connor’s gun. Then he found his footing, pistoned his legs forward, and drove his body headlong into O’Connor.

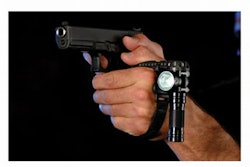

Simultaneously, his right hand reached down for his own gun. In a fluid motion, the gun escaped its holster and Alford jammed it toward the man’s center mass. In an instant, the safety was off and Alford fired four quick shots into O’Connor’s torso.

Dewey Clemons saw an opening. As O’Connor’s flank came into full view, Clemons opened fire. A single round from Clemons’ own 9mm pierced the suspect’s upper torso, taking out the top of O’Connor’s aorta.

The combined firepower of Alford and Clemons dropped O’Connor like a stone. He was subsequently transported to an area hospital and pronounced dead.

Dangerous Assumptions

Alford was flown to Roanoke Memorial Hospital where he was treated for a through-and-through wound that clipped the top part of his lung.

A subsequent examination of O’Connor’s weapon revealed that after firing his first round, he had apparently hit the button release of his magazine which fell to the floor, effectively preventing his ability to take a second shot. Of course, there was no way for either Alford or Clemons to know that.

Looking back, Alford recognizes where he could have done things differently, and he uses such lessons while teaching cadets.

He cites his own mistakes: His willingness to downplay the importance of telltale signs such as O’Connor’s vacillating travel itinerary, the man’s sudden shift from standoffishness to overt compliance, and Alford’s own failure to consider that a second weapon might be accessible.

“But the biggest mistake that I made was not securing the suspect,” Alford says. “Once we had secured the first weapon, we’d made the dangerous assumption that there were no more weapons to be worried about. It’s an absolute example of a fatalistic mindset. I did have one thing going with my mindset though, and that was if I was going to die I was not going to go out without fighting and as long as I was in the fight I had a chance to survive.”

For pre-academy Officer Clemons, the baptism by fire let him know beyond a doubt that the job was not only one that he could, but one that he was destined to do. And he has spent the past 17 years doing just that.

For all of their introspection, both officers have a legitimate concern, one that they wonder about to this day: whether or not the episode might have been averted entirely. For although the New York robbery had occurred on Dec. 22 and the Albany Police Department had distributed a local teletype, nothing had been put into NCIC until the very morning that Alford confronted O’Connor.

“Between the teletype and other factors, things should have gone differently,” Alford concludes. “Perhaps I wouldn’t have gotten shot. And I wouldn’t have had to kill him.”

Dean Scoville is a patrol supervisor with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and a contributing editor to Police.

Consider These Questions

Think about the situation that faced Officer Martin Alford of the Wytheville (Va.) Police Department.

• Officer Martin Alford has been and continues to be generous in sharing the benefits of some very difficult officer survival lessons. Generally speaking, how candid do you think most officers are when it comes to acknowledging mistakes that they have made in the hopes that others will profit by the lessons that they have learned? Are cops more concerned with their ego than they are with the safety of their fellow officer?

• How accommodating is the law enforcement arena in encouraging candidate critiques and discussions of officer-involved shootings? To what extent do the following factors inhibit officers from being candid regarding their personal experiences: Threat of litigation, fear of peer criticism, administrative fallout, denial?

• How do you conduct your field interviews of detained individuals? At what point do you decide to place them into custody? What steps do you take to ensure that this can be done safely?