At 11:17 p.m., a 911 call came in to the Tallahassee police dispatch center. The man on the telephone identified himself as Louis Green and advised that he had warrants and wanted to turn himself in. He described himself to the dispatcher, said that he would await the responding officers at 2403 South Meridian Street, and hung up.

After Louis Green hung up his phone, he walked outside his house and took a seat on the porch. Green was no stranger to the police. His criminal record—while not particularly distinguished—wasn’t exactly a blank slate, either. When he hadn’t been out conducting forgeries and shoplifting, Green had committed a series of felonious batteries and assaults, largely domestic in nature. And somewhere along the line, he had even squeezed in a suicide attempt, ingesting pills before dialing 911 and asking for police intervention.

Perhaps the sounds of police sirens descending on his neighborhood reminded Green of something long overdue. But after tonight, there’d be no more procrastinating, no more second thoughts. Things would be resolved once and for all. All he had to do now was wait for his unknown and unknowing benefactor to arrive. Green took a series of drags from his cigarette, watching its amber glow grow brighter with each inhale before darkening.

The Rookie

Officer Russell Huston was 24 years old and seven months out of training the night Green called the Tallahassee Police Department. It had been a busy shift already. Most of the field force was tied up on two separate containment operations and searches for outstanding suspects who had bailed out on routine traffic stops. Wanting to do his part, Huston ran a check of calls waiting to be handled. He noticed one that was commuter friendly on South Meridian: a suspect wanting to turn himself in. He acted on it.

As he rolled, Huston was advised by dispatch that despite the man’s claims, no warrant information had turned up in response to database queries on the caller’s name. But then, they’d run the name as “Lewis” instead of “Louis.” In fact, Louis Green had an outstanding civil contempt warrant.

Both of his parents had served in law enforcement, so Huston had never been particularly naïve about the vagaries of the job. His father Ron Huston was a deputy with the Indian River County (Fla.) Sheriff’s Office. His mother Debbie Huston was a sergeant with the Sebastian (Fla.) Police Department.

Huston’s mother and father had made it a habit to periodically remind their son of the inherent dangers of the job. As a result, Russell Huston made it a habit to use backup when it was available.

Diversionary Tactic

Now, Huston was rolling to Meridian Street, the kind of area where the thought of backup came naturally. Crack heads, crack houses, and crack whores were present and accounted for, and its own citizens lived in a constant state of condition yellow. It was the prototypical bad neighborhood.

Pulling abreast of Officer April Doubrava, a fellow squad officer who was parked in the 2500 block of Meridian Street holding containment on an earlier incident, Huston advised Doubrava of his call and asked if she could drive with him. Doubrava, a veteran officer, said, “Sure.”

She pulled behind Huston and used her in-car computer to retrieve the CAD (Computer Aided Dispatch) notes of the call.

As Huston navigated his way northward on Meridian, he noticed that the curbside numbers had long since faded and worn off, no doubt in part due to the numerous patrol cars that had pulled to that same curb over the years. With no discernible numbers to read, Huston accidentally drove past the location.

Huston made a U-turn and doubled back. As he turned, Doubrava raised Huston on the talk around channel.

“They couldn’t find anything on this guy,” Doubrava relayed. “I’m beginning to think this is maybe one of those diversionary calls designed to pull us off the containment and let our bad guy escape. I’m going back to my spot, but don’t hesitate to call me if you need me.”

Doubrava’s speculation made sense to Huston, too. It wouldn’t have been the first time a suspect or one of his homies had called in with a bogus story designed to get officers on a containment to roll elsewhere.

Huston waved Doubrava off and continued on his own. If anything suspicious came up, he had the peace of mind of knowing Doubrava was keeping him in eyeline from her location, some 1,000 feet south of the Meridian address.

Going Alone

Huston pulled up south of the house and on the opposite side of the street in front of an abandoned convenience store. He exited the driver’s side of his car and started to cross the street for Green’s house. His gait was consciously casual, allowing him the opportunity to survey the terrain while hopefully lessening any understandable anxiety his informant might have upon his approach. It didn’t make sense to come on like gangbusters and either spook the guy into having second thoughts about surrendering or agitate any possible defensiveness from his informant.

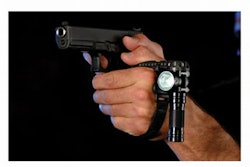

A few steps toward the white brick duplex, Huston spotted in the darkness on the south side of the house the silhouette of a man seated on a porch. He pulled his Maglite out of its belt ring.

“Hi,” Huston said to the man. “How are you doing?”

Cold Steel

Louis Green wasn’t in the mood for conversation. He flicked away his cigarette, sending it cartwheeling into the night. Then he grabbed something that had been resting at his side, jumped up, and charged at Huston.

As Green surged at him, Huston’s night vision rapidly improved, pupils dilating to take in as much detail as possible. One of the details he now noticed was the gleam of an overhead street lamp reflecting off an object his attacker held raised over his head.

It was a three-foot axe aimed right at Huston’s head.

The Tueller Drill

Big on officer survival training, and good at it, Sgt. John Parsons was known among Tallahassee recruits as “The Scary One.” More than one veteran officer had vicariously profited from Parsons’ lectures, including Huston.

In particular, Sgt. Parsons’ test of the 21-foot rule popularized by Salt Lake City trainer Dennis Tueller had stuck with Huston. Taking a position at the opposite end of the briefing room, the “knife”-wielding Parsons told his volunteer officer and onlookers that he would close a 21-foot distance and take out the officer before the officer could retrieve his sidearm and defend himself. And just like that, The Scary One had another notch on his belt.

Shoot Me!

Huston remembered “The Scary One” and his graphic demonstration rule. And now it was happening for real.

A man was charging him with an axe. He was 20 to 25 feet and galaxies of sanity away.

Huston’s life was threatened. And he knew one thing, he didn’t want to be murdered with an axe.

Huston knew he could no more meet the threat head-on than he could turn on his heels and run. Green screamed, “Shoot me! Shoot me!”

Huston backed up and drew so quickly that his gun seemed to magically clear his SS 3 Safariland holster and materialize in his hand. His only hope was to draw and fire as quickly as possible while simultaneously putting distance between the suspect and himself.

It was little more than reflexive point and shoot. Three rounds from Huston’s .40-caliber SIG tore into Green’s upper torso, dropping his body at Huston’s feet.

Two of the rounds caught Green in the left side of his chest. As he spun, a third entered and exited an arm.

Green went down and didn’t make a sound. He was pronounced dead at the scene.

Doubrava doubled back at the sound of the shots. She found Huston standing about five feet from his patrol car, his gun pointed in a two-fisted grip at the suspect. To minimize crossfire threats to one another, they approached Green in an L-formation.

Racial Issues

Green was black. In a Southern Town. Killed by a white police officer. The shooting stirred a hornet’s nest.

Black ministers of the Southern Christian Leadership Coalition saw the shooting as a rogue cop’s bid to avenge the killing of Tallahassee PD Sgt. Dale Green two years before. They accused Huston and his fellow officers of planting the axe and orchestrating a cover-up.

One of the first questions that investigators posed to Huston was whether or not he was in the habit of carrying an axe in the trunk of his patrol car. At the time, Huston might have felt a little offended. In retrospect, he appreciated the fact that the investigators had done such a thorough job.

And the department stood behind him. Prior to Huston’s testimony in court, a use-of-force expert, Sgt. James Fairfield, conducted a two-hour presentation explaining the department’s use-of-force matrix.

A dynamic and charismatic speaker, Fairfield gave the 21 members of the grand jury a thorough overview of the thought processes and decision making that officers use when it comes to dealing with a variety of threats as well as when less-lethal or lethal force was necessary.

Fairfield’s presentation was so effective that by the time Huston was obligated to speak, his presence on the stand lasted only minutes, long enough for him to tell his side of the story and to answer a few clarifying questions.

Relegated to a court hallway to await the jury’s decision, Huston anticipated a long wait. But after a few minutes, the lead state attorney general came out, shook Huston’s hand, and said, “It’s unanimous.”

Huston was greatly relieved at the grand jury’s findings. Still, he was somewhat disappointed that the local news media, which had been so fixated on a possibility of a cover-up, proved to be so disinterested in his eventual exoneration. The grand jury’s finding barely rated a comment in the news columns.

Huston is thankful for the training he’s received from his department, particularly impromptu refresher courses, such as was routine in Sgt. Parsons’ briefings. He readily acknowledges his debt to each.

Dean Scoville is a patrol supervisor with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and a contributing editor to Police.

Shots Fired: Tallahassee, Florida 06/26/2004

At 11:17 p.m., a 911 call came in to the Tallahassee police dispatch center. The man on the telephone identified himself as Louis Green and advised that he had warrants and wanted to turn himself in. He described himself to the dispatcher, said that he would await the responding officers at 2403 South Meridian Street, and hung up.