Every U.S. Supreme Court decision on the criminal justice provisions of the Constitution (especially the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Fourteenth Amendments) is important to law enforcement, but some have a more significant day-to-day impact on police work than others. In terms of the changes they created—whether imposing new restrictions and procedures or allowing greater enforcement activity—the following cases have a lasting impact on law enforcement officers in the four important areas of officer safety, searches and seizures, questioning of suspects and witnesses, and civil liability.

Officer Safety

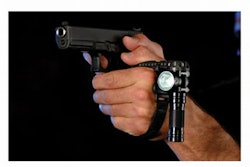

Most of the cases discussing use of force and other safety topics have been sensitive to the dangers of police work, allowing necessary protective measures to be taken during high-risk activities. But the Supreme Court also drew lines and imposed limits on the use of force, especially deadly force.

1977 Pennsylvania v. Mimms. For officer safety, officers can routinely order the driver out at any lawful traffic stop, and no reason need be given. A visible bulge in the driver’s clothing justifies a weapons frisk.

1984 New York v. Quarles. Custodial questions aimed at neutralizing an immediate threat to officer safety or public safety do not have to be preceded by Miranda warnings, as in “Where did you put the gun?”

1985 Tennessee v. Garner. Officers may constitutionally use deadly force as necessary to prevent escape only where the suspected crime involved the infliction or threatened infliction of death or serious bodily injury, and where some warning is given, if feasible.

1989 Graham v. Connor. The constitutionality of any use of force depends on the severity of the crime, whether the suspect poses an immediate threat to officer safety or public safety, whether he is actively resisting or attempting to evade, and the nature of the force used.

1990 Maryland v. Buie. Incident to a lawful in-home arrest, officers may look into immediately adjoining spaces that could conceal an assailant. A “protective sweep” of the entire premises can be conducted if there is articulable suspicion that an assailant may be present.

1997 Maryland v. Wilson. For officer safety, officers can routinely order all passengers out at any lawful traffic stop, and no reasons need be given. Contraband or other evidence then seen in plain view may be seized.

Search and Seizure Issues

Fourth Amendment cases continued to refine the rules affecting warrantless entries into homes, warrantless arrests, and warrantless searches, especially of vehicles. The court also created the concept of the “consensual encounter,” and generated a need for new procedures in most states to obtain a judicial probable cause determination for warrantless arrests. While most of the major decisions enlarged investigative leeway, a few imposed new restrictions.

1978 Mincey v. Arizona. Eliminated the “homicide scene exception” for warrantless searches, ruling that once exigencies end, a warrant is needed for any further searching.

1979 Dunaway v. New York. Picking up a suspect and “taking him in for questioning” is a de facto arrest, which is unconstitutional if there is no PC for the arrest.

1980 Payton v. New York. Non-consensual, non-exigent entry of a residence to arrest an occupant requires an arrest warrant.

1980 U.S. v. Mendenhall. Police may engage an individual in a “consensual encounter” without any suspicion or justification, provided no official pressures are employed to prevent the person from going about his or her business. Consent to search may be requested, and plain-view observations may be made that may justify detention or arrest.

1981 New York v. Belton. Incident to the lawful arrest of any occupant of a lawfully stopped vehicle, officers can conduct a warrantless search of the passenger compartment, including all containers and receptacles (but not the trunk). This search must be conducted at or near the time and place of the arrest.

1982 U.S. v. Ross. With probable cause and lawful access, police can make a warrantless search of a vehicle, including any spaces and containers that might conceal the object of the search. The scope of search is the same as a magistrate could authorize by warrant.

1991 County of Riverside v. McLaughlin. A judicial officer must review and approve the probable cause for a warrantless custodial arrest not later than 48 hours after arrest. This is typically done at arraignment or a probable cause hearing, or by judicial review of a written declaration made by the arresting officer.

1991 California v. Acevedo. Extending the holding of Ross relating to vehicle searches based on probable cause, the court held that the scope of vehicle searches includes closed containers that might conceal the object of the search. This case overruled several former decisions that had made a no-search exception for closed containers found in vehicles.

1996 Whren v. U.S. Officers can make a “pretext” vehicle stop based on traffic violations, even if they also want to investigate possible criminal activity. Because traffic violations are very common, this case makes it possible for officers to stop practically any vehicle they may need to investigate. Activities cannot exceed the scope of the traffic stop, unless plain-view observations or other circumstances expand the lawful scope of the stop.

1996 Ohio v. Robinette. At any lawful traffic stop, police can request consent to search the vehicle, even though they have no suspicion of wrongdoing. There is no requirement to advise the person of his or her right to refuse consent.

2001 Atwater v. Lago Vista. An arrest based on probable cause is constitutionally permissible for any level of offense, regardless of the prescribed penalty. A person arrested for a traffic offense can be taken into custody and subjected to an immediate search incident to arrest, a booking search at the station, and a standardized inventory of the lawfully impounded vehicle.

Questioning of Suspects and Witnesses

The court continued the trend of curtailing the application of Miranda, defining “custody” so as to allow questioning during ordinary detentions and voluntary stationhouse interviews, and making clear the non-constitutional character of “Miranda rights” for purposes of admissibility of derivative “fruits.” Court decisions also stressed that “involuntary” statements that are actually coerced by mistreatment, threats, or promises of leniency are completely inadmissible for all purposes. The court rejected a congressional attempt to limit Miranda, indicating that Miranda is not likely to disappear from the legal landscape anytime soon. And a Sixth Amendment “confrontation” case changes the way first responders seek information from victims of certain kinds of crimes.

1977 Oregon v. Mathiason. Voluntary stationhouse interrogation of a suspect is not custodial and therefore not subject to Miranda, where the suspect comes in voluntarily, is told and treated as if he is not under arrest and can leave at will, and makes incriminating admissions.

1978 Mincey v. Arizona. “Involuntary” statements produced by coercive interrogation techniques violate due process and are inadmissible for any purpose at a criminal trial.

1979 Butler v. North Carolina. In at least some circumstances, a Miranda waiver need not be express but can be implied if the suspect acknowledges that he understands the recited rights and then makes a statement or answers questions.

1981 Edwards v. Arizona. Once a custodial suspect invokes the Miranda “right” to counsel, no admissible statement can be obtained via police-initiated questioning without counsel present, assuming no break in custody.

1984 Berkemer v. McCarty. Miranda “custody” is formal arrest or its functional equivalent, and does not include ordinary temporary detentions in the field, accomplished without guns, cuffs, caging, or other indicia of formal arrest.

1985 Oregon v. Elstad. Brief custodial interrogation without Miranda warning and waiver upon arrest does not necessarily preclude an admissible post-warning statement at a later time.

1990 Illinois v. Perkins. Miranda does not apply to undercover questioning inside a custodial facility, because a suspect who is unaware he is talking to a police officer or agent is not presumed to feel compelled by official pressures to incriminate himself.

1994 Stansbury v. California. A police officer’s subjective “focus of suspicion” is irrelevant to the determination of whether a suspect is in custody for Miranda purposes.

2000 Dickerson v. U.S. Although the Miranda procedures for ensuring admissibility of a statement obtained through custodial interrogation are “prophylactic measures” that are not themselves rights protected by the Constitution, the basic ruling of Miranda—that non-complying statements are inadmissible to prove guilt during the prosecution case-in-chief—is a “constitutional rule” necessary to protect the Fifth Amendment trial privilege against compelled self-incrimination. This admissibility rule being required by the Constitution, Congress was not free to overrule it by legislation.

2001 Texas v. Cobb. The Sixth Amendment right to counsel that attaches with the initiation of adversary judicial proceedings (usually, indictment or arraignment) is “offense specific” and does not prohibit questioning on related or unrelated crimes that are not “lesser included offenses” of the charged crime.

2004 Missouri v. Seibert. Lengthy pre-warning custodial interrogation undermines the meaningfulness of a subsequent Miranda warning and waiver, rendering confessions obtained by a deliberate “two-step strategy” inadmissible. If police “question first” and give a midstream warning, neither the unwarned “softening-up” statement nor the post-warning statement is admissible under Miranda. Elstad continues to apply where pre-warning questioning during the arrest was brief and was not a deliberate ploy to circumvent Miranda.

2004 U.S. v. Patane. Because Miranda procedures are not themselves constitutional rights, physical evidence discovered through questioning “outside Miranda” is not subject to exclusion as “fruit of the poisonous tree.”

2004 Crawford v. Washington. “Testimonial” witness statements produced by “structured police questioning” (such as from domestic violence and child abuse victims) are not admissible at trial where their use would violate the defendant’s Sixth Amendment right of confrontation, if the witness is not subject to cross-examination at trial or some prior proceeding. First responders may need to ask, “What’s happening?” and take a volunteered, narrative statement before resorting to structured questioning.

Civil Liability

The court expanded the ability of plaintiffs to hold public entities liable for their employed officers’ violations of constitutional rights, but also issued two significant decisions erecting barriers to civil liability against law enforcement officers.

1978 Monell v. DSS of New York. A civil rights lawsuit can be maintained against the police department or the municipality if it can be shown that an officer’s official conduct violating the plaintiff’s constitutional rights was pursuant to the official policy or practice of the department or agency.

1989 City of Canton, Ohio v. Harris. The department and the chief or sheriff can be held liable for civil rights violations resulting from their deliberate indifference to the duty to train and supervise their officers.

1994 Heck v. Humphrey. A plaintiff cannot maintain a civil rights lawsuit against the department or its officers if a judgment in the plaintiff’s favor would necessarily imply the invalidity of an existing criminal conviction. Once the criminal defendant pleads guilty or is convicted at trial, he or she cannot sue for claims inconsistent with the conviction.

2003 Chavez v. Martinez. Law enforcement officers cannot be sued under the federal civil rights act for violating a suspect’s Fifth Amendment privilege against compelled self-incrimination, which is a trial right. Civil rights liability cannot be based on an officer’s non-compliance with Miranda procedures, which are admissibility prerequisites only and not themselves constitutional rights.

Looking Ahead...

The next 30 years are sure to bring many more Supreme Court decisions having dramatic impact on the way police officers do their jobs. The explosion of high-tech crimes such as cyber fraud, identity theft, and Internet pedophilia and pornography will require the court to act quickly to allow law enforcement to adapt crime-solving techniques to constantly changing technology. Threats of youth gangs victimizing neighborhoods and international terrorists targeting the U.S. homeland will also challenge existing restrictions on searches and seizures, especially in the areas of surveillance and criminal profiling. And innovative investigative techniques for traditional criminal conduct will continue to come before the court for evaluation of their constitutionality. Our monthly “Point of Law” column will keep you abreast of important decisions, as they are issued. Stay tuned.

Devallis Rutledge, a former police officer and veteran prosecutor, is Special Counsel to the Los Angeles County District Attorney.

30th Anniversary: High-Impact Decisions

Every U.S. Supreme Court decision on the criminal justice provisions of the Constitution (especially the Fourth, Fifth, Sixth, and Fourteenth Amendments) is important to law enforcement, but some have a more significant day-to-day impact on police work than others.