It’s zero dark thirty and you’ve responded to a suspicious person call in the parking lot of a local bar frequented by members of the area’s one-percenter biker population. As you begin to field interview the subject, he suddenly closes the distance of your reactionary gap and is all over you. You try to hold him off, and his hand suddenly moves to a leather sheath on his belt and attempts to grab his blade.

Then and there among the closely parked cars, motorcycles, and broken glass you’re in a fight for your life with a beer-breathed, bearded behemoth bent on your destruction. Now is the time to muster all of your skills, abilities, and attributes to win the day. Now is the time you will revert to the lessons learned in training. The question is: Did you train for such up close, personal, and violent encounters?

Most experts will tell you that the average distance for a police shooting is 20 feet, but that’s a misleading stat. The reality is that a lot of deadly force incidents take place within 10 feet and even closer.

Think about it; under 10 feet is the distance of police social interaction, whether good or bad. So odds are that if you’re going to be attacked, the bad guy will make his move when he’s right on top of you.

Space is Time

Space is more than the “final frontier” as Captain Kirk intoned at the beginning of the original “Star Trek.” Space is a valuable asset that you can use to buy time. But when your attacker is within six feet, there’s not a lot of time to buy. Within six feet, every attack is an emergency.

Increasing the space is not a complete solution to the problem. For example, if your attacker has a gun and you turn and run, you will get shot in the back. In addition, since you are reacting to the suspect’s attack, he or she has the advantage of time. So it’s unlikely that moving away will save you. Finally, where exactly in the real world of your patrol area is there enough space that a sudden retreat is possible? Clean avenues of retreat tend to only exist in the sterile environment that trainers have available, such as gyms and training rooms. Try a bob-and-weave tactic in a tenement living room, parking lot, or back alley and see how it stands up.

So what are your options for response to a sudden attack at close range? In simple terms, you can either open distance or close it. If you are behind in terms of reacting, it’s better to crash with the suspect than to try to stand and outdraw your opponent who already has his pistol drawn. To engage in a shootout at this distance may result in what Filipino martial artists call a “mutual slay.”

Yes, the bad guy might have a knife and you might have a gun, but time/distance and lack of readiness may preclude you from getting your pistol out fast enough to stop the suspect before he uses his weapon. Don’t believe me? Try the following drill.

Using a non-functional training gun like a Blue Gun, have someone stand six feet from you with a wooden spoon or training knife held behind his or her leg. When this person begins to strike, try to draw your training gun from your holster before he or she can stab you. Now have your “attacker” safely add some forward pressure, as if he or she were trying to stab you multiple times. This will make it clear to you that although you are armed with a superior weapon, someone close up on you with a knife may have the advantage.

Reaching Out

The good thing about having your attacker right up on you is that anything you do will immediately affect him. Inside touching distance, merely reaching out will put hands on the suspect. At eight feet, one step and reaching out will put your hands on him.

Your best reaction is to move into the attack and counterattack. Imagine that a suspect draws a knife on you at arm’s distance. If you attempt to stand and draw, the result will be multiple knife wounds. So instead of attempting to draw, stop the suspect’s violent attack, counterattack, and use your counterattack to buy time so that you can draw your sidearm and respond with deadly force. Using this tactic, you are much less likely to be seriously injured by a close-up assault. You may even escape harm.

In any close-in engagement, remember the following points:

• You must win the fight. There is no alternative, and you must do whatever you can to win.

• Use your counterattack to buy time and gain the advantage.

• When you have the advantage, access your pistol and bring it into play.

Block, Parry, Strike

Here’s how to gain the advantage in a close-in attack.

In the defensive context, your hands and arms are capable of three actions: You can block an attack, parry an attack, strike back, or perform a combination of these moves. I say “hands and arms” because you may strike with a palm, fist, forearm, or elbow.

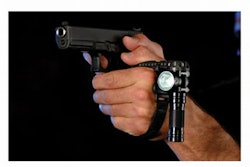

It’s possible for you to use one hand to strike a suspect or keep him off of you, so that you can draw your pistol and position it in a stable position from which you can successfully shoot. However, if the suspect is attempting to impede your draw or disarm you, you may need both hands.

First, stop your attacker’s attempted takeaway, clear his hand from your pistol, then create enough space to shoot and accurately deliver deadly force. If you use two hands to block the attack by grabbing the offender’s arm, this only gives you the ability to make defensive moves such as head butts, knee strikes, stomps, or some other type of low line kick.

Blocking the drawing movements of your assailant’s hand to his weapon is referred to as “fouling the draw.” This is one of your most critical concerns during a close-in fight. Stopping his drawing movement allows you to strike with your other hand, maybe strip any weapon already in his hand, or draw and fire your weapon if necessary.

[PAGEBREAK]

Shooting Positions

Any firearms instructor will tell you that the most stable and therefore accurate shooting position is with two hands at eye level. But during a close-in fight with an attacker, you probably won’t be able to achieve this position and protect your weapon.

When your attacker is right on top of you, you may need to shoot from belt level or hip positions. You also may need to protect your pistol by assuming some version of a chest tuck. Remember, at this range, any shooting position that places your pistol away from your center may make it easy for your attacker to grab it.

Another concern when you are drawing your pistol to stop a close-in attack is that you must keep your muzzle off of your own body. This sounds easy. But it isn’t when you are struggling with a determined attacker.

Closing the Training Gap

If you have never shot from any position except two-handed at eye level and you’ve never drawn your weapon while struggling with someone who is trying to take it away from you, then there are gaps in your training. You need to train for the conditions and types of attacks that you might encounter on the street.

Most firearms instructors think that firearms training must be live fire. The problem with this approach is that it prevents you from training to respond to the most likely attack you will face in the real world, the close-in assault.

This means that when you are attacked by a committed assailant who is within arm’s reach, you have no firearms training to help you counter the attack. You have to make the untrained jump to incorporating empty hand and gun. As any good police trainer will tell you, the street is not the place to develop tactics. Training should have already provided you with a programmed response based on this threat stimulus.

Meaningful firearms training does not have to include live fire. By using non-functional training guns such as Blue Guns, you can train to realistically integrate empty hand and pistol techniques.

The following training drills can teach you how to respond—both with your empty hands and with your sidearm—to sudden close-in attacks:

• With your training partner to the front applying forward pressure, create space and shoot.

• With your partner to the front attempting to foul your draw, create space and shoot.

• With your partner to the front attempting to disarm you, stop the attempted takeaway and shoot.

• With your partner to the front attempting to stab you, stop the assault, control your partner’s arm, and shoot.

• With your partner to the front attempting to draw a pistol from concealment, foul the draw, control your partner’s arm, and shoot.

• With your partner to the rear attempting to bar arm choke you, protect your airway, and shoot.

• On the ground with your partner on top of you, create space and shoot.

• On the ground, with your partner on top of you with his or her hand on your holstered pistol, stop the takeaway, create space, and shoot.

• On the ground with you on top, create space and shoot.

• On the ground with you on top and your partner’s hand on your holstered pistol, stop the takeaway, create space, and shoot.

Spontaneous and Non-Spontaneous Assaults

You need to train for both spontaneous and non-spontaneous assault.

In a non-spontaneous assault, you have time because the nature of the call or other pre-assault cues have tipped you to draw your pistol in advance, increase the distance from the suspect, get to cover, verbally challenge the suspect, and take other measures that will prevent an attack. In a spontaneous attack, you don’t have these cues and you don’t know to draw your pistol in advance. Most spontaneous assaults are some version of an ambush.

Sadly, most firearms training is conducted on a square range with the focus on non-spontaneous situations, and it does not prepare you to react to spontaneous attack. Incorporating realistic empty hand skills with the use of your pistol will prepare you to win regardless of the close distance and conditions.

So, take the time and engage in close or extreme close quarters firearms training. This will prepare you to win the fight in the event things get extremely violent, up close, and personal.

The author wishes to thank Rob Pincus of Valhalla Training Center (www.valhallatrain ing.com) for his assistance with this article.

Kevin R. Davis is a full-time law enforcement officer with 24 years of experience. Currently assigned to his agency’s training bureau, he is a former SWAT team leader and lead instructor. Davis’ Website is ww.advancedtacticalconcepts.com. He welcomes your input at kd1@advancedtac ticalconcepts.com.