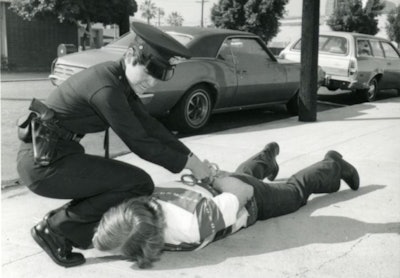

A female police officer makes an arrest in the 1980s. Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Police Historical Society.

A female police officer makes an arrest in the 1980s. Photo courtesy of Los Angeles Police Historical Society.

It's difficult to determine when the first American female police officer pinned on her badge and began her watch. Several departments say they swore in the first "police woman" sometime around the turn of the 20th century so the issue is contested. It's easier, however, to pinpoint the dawn of the contemporary female officer, that one moment in time where law enforcement's and the public's attitude toward women with badges began to change and female officers began to be perceived as "real police." That year was 1972.

Forty years ago women didn't have much of a toehold in law enforcement. A mere 2% of all police officers and sheriff's deputies nationwide were female. Yet there was a growing presence of female officers and a growing recognition that female officers could take on duties that were once thought only suited to men.

Of course, women who wore badges in the 1970s faced old school stereotypes and biases, both within their departments and from the public. They were also accorded little consideration in sartorial matters, as they were required to wear impractical skirts, high-heeled shoes, and unisex ballistic vests that ignored the natural contours of the female figure. It wasn't even until the late '70s that Sally Brownes—uniform belts designed for women—were widely used. Before that belt was available, female officers kept their weapons and handcuffs in their purses.

Assignments were also an issue for pioneering female officers. They were shuffled into female-only duties, given desk and clerical work, sent to women's jail wards, or posted to juvenile investigations units. But in the 1970s some female officers fought for and won patrol positions that would serve as promotional stepping stones.

These early '70s female officers fought for and won respect. They also paved the way for more and more women to become officers.

A generation later, female officers make up 14 percent of the Thin Blue Line, and their ranks are growing. Female officers have yet to reach parity with their overall representation in society, but women have successfully integrated themselves throughout the ranks of law enforcement, serving as integral members of SWAT teams, K-9 units, investigation divisions, training staffs, and special task forces. Many have even gone on to helm major police departments as chiefs.

To trace the arduous path that women have forged in law enforcement, POLICE contacted women who worked their way up the ranks starting in the 1970s. Their personal experiences tell the story of what it's like to be a female pioneer in a male-dominated profession.

Hitting the Streets

Patty Fogerson retired in 1994 as a detective supervisor III with the Bunco Forgery Division of the Los Angeles Police Department. Her career was even the subject of a television movie of the week starring Linda Hamilton. She says initially there was much trepidation on both sides of the sexual fence.

"My first partner didn't know whether he should open the door for me when we got in the car," reflects Fogerson, who joined the department in 1969.

Also in Southern California that same year, Judith Lewis was starting her law enforcement career with the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department.

"When I joined the department," Lewis says, "we were called 'lady deputies.' Our uniform was a skirt, high heels, and a blouse. We went through a 10-week academy vs. a 20-week academy for men. We got a 2-inch gun to carry in our purse. I was a deputy in an administrative job."

Lewis went on to play an instrumental role in creating a program to usher women from working behind the desk to working the front line. In exploring this new territory, her task force encountered its share of hurdles on both sides of the gender line. And she wasn’t even sure that she wanted to hit the streets.

From the female perspective, Lewis explains, "I didn't want to go to patrol at that time because I had three small kids. Patrol wasn't what I joined the job for, and neither did most women. Opinion was mostly negative in the department to do that."

As Lewis' task force searched for positions for women on the department, a detective from the automotive division piped up, saying that women couldn't or wouldn't work there because they would have to crawl under cars to find VIN numbers. "I replied that I knew some obese male officers who couldn't do that job," recalls Lewis.

Retrained

Eventually, at Lewis's request, the department asked for volunteers rather than implementing a draft. The first women on patrol were still required to wear high heels, a purse, and a skirt, but some women violated the rules and improvised their own uniforms for practical purposes.

And before they could become full-fledged patrol officers, women had to pass full academy training. For women like Fogerson, who had already completed a shortened training course designed for police women, a second round of academy training was required.

"In 1975, I experienced some double standards in the academy," says Fogerson. "Physical training instructors in the academy didn't want us there, and they made life as difficult as possible for us. One guy changed my time on the obstacle course. I had won medals in the Police Olympics, so I had done well. But he read off my time as being slower than the slowest person there."

Fogerson's response was to glare at the instructor who posted the bogus time. "He looked at me and asked, 'Do you have a question about your time?' I said, 'No, sir.' He said, 'Good.' I ended up having to do 10 pull-ups instead of four to pass the exam.”

Such harassment and hazing was commonly inflicted on early female recruits for patrol duties, but Fogerson and others are quick to note that many instructors and supervisors treated them fairly. While they could not excuse subtle or overt forms of discrimination that they experienced, they made the point that both men and women were subject to various acts that were largely dictated by their newness to the profession rather than their gender.

Trying Harder

Sexual harassment was also a common experience for these female pioneers, particularly in the early years. Unfortunately, there was not much that they could do about it.

"Phrases like 'sexual harassment' and 'hostile work environment' didn't exist back then," says Fogerson. "My attitude was, get the job done and you'll be able to prove yourself. I was able to work robbery and detectives, background investigations, and was one of the first female drill instructors in the academy. I just got along and survived in the beginning, then things settled down."

Former Tucson, Ariz., officer Ruthanne Penn agrees that the females she knew tended to try harder. In part, because they had to. "Males wouldn't be considered a screw-up until they made 10 mistakes," she reflects. "A female could make only one mistake and be considered a screw-up."

Standing Out

John Wills, a former Chicago police officer and FBI agent and the author of the forthcoming "Women Warriors: Stories from the Thin Blue Line," is sympathetic to Penn's observations.

"Women stand out a little quicker when they make mistakes than their male counterparts," Wills notes. "They stand out to the public and to their male counterparts because of their numbers. Large departments with lots of women on the street don't have that problem. But in a small department with only two women on a watch, if one makes a mistake it sticks out like a sore thumb."

Penn cites a peer's unfortunate experience as a prime example. While the error made was not demonstrably different than those made by male officers, it proved to be one that the woman had a particularly difficult time living down. For a time it also made Penn, who worked in law enforcement from 1976 to 2001, hyper vigilant against making errors. Eventually, she relaxed. Not because she became apathetic to the prospect of committing some transgression, but because she simply acquired faith in her own abilities.

"After I'd been working for a while, I felt good about what I did so I didn't care what men thought of me," Penn says. "In the beginning there was a lot of pressure, for about five or six years. After several assignments, particularly when I became a detective, I was more confident. We were all on the same playing field."

Promotions and Legal Action

Unfortunately, hard work alone could not bridge the gender gap that existed in many department policies, particularly as they related to promotional opportunities for women.

Capt. Rebecca Meeks with the Waynesboro (Va.) Police Department recalls her promotional struggles. "When I tested for lieutenant, I outscored a man who was promoted before me. They said it was because he had a four-year degree and I had only a two-year degree. It was the chief's call. I'd heard that he asked other captains who they wanted to be promoted, so I felt discouraged. But the man who was promoted was an excellent supervisor, so I didn't hold it against him."

Faced with similar discrimination, two Southern California female officers stood up on behalf of their peers and filed lawsuits against their departments.

In 1973, a sergeant with the LAPD, Fanchon Blake, sued after she and other female police sergeants were not allowed to take the lieutenant's exam because they were women. She won. A similar lawsuit filed against the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department by Sue Bouman in 1980 was eventually settled in 1988.

Among the legacies of these landmark suits were decrees that required departments to make amends to women in law enforcement. These guidelines were designed to bolster the presence of women in the profession and to remove barriers for promotion and assignments to coveted positions. They served as precedents for departments across the country to implement similar policies.

"Promotional boards are much different in today's environment when you're trying to promote from patrol," notes Wills. "The testing process has evolved in terms of being more academic, especially with more technology being involved in police work."

Still, it has not been easy for women to stand up for their rights in their law enforcement careers.

Lewis recalls the hardships that Bouman and others experienced in the wake of taking their stands against their departments. "Back then there really was no place for women to go with sexual harassment or job discrimination complaints, and it would definitely negatively affect your career if you complained publicly. By the time I left, there were places for women to go and either talk to someone confidentially or to place a formal complaint. However, the one thing that still existed in a few cases, was a peer and career backlash for making such a complaint. Sue Bouman paid heavily for her lawsuit and was the subject of continuing hard feelings and backlash against her for the rest of her career."

Few Role Models

To counter the chilling effects of harassment, discrimination, and negative stereotyping on the job, women officers have turned to one another for support.

But for those women who were part of the vanguard for women in law enforcement, mentors and role models were in short supply. It was not only up to many of these women to undergo a baptism by fire, but to ultimately become mentors and role models themselves.

"There were role models for the jobs that women had traditionally done," Lewis recalls, "but there were no role models for women working patrol. The women who went out to patrol early became role models for those who came later."

Some, like Lewis, tried to establish formal mentoring programs. As recently as 1998, the International Association of Chiefs of Police concluded that while the need continues to be great, there are very few mentoring programs for women officers. What support there was typically came from informal contacts.

"The support women sergeants gave us was mostly in the locker room, urging us on," recalls Fogerson.

Wills notes the importance of formal organizations for women in law enforcement. "In some parts of the country, women are still a minority. They need women's organizations for the smaller contingent on smaller departments to give them support and direction.”

To that end there is no shortage of organizations developed by and for women, including a growing cadre of instructional institutions that focus on providing women gender specific training in areas of promotional and officer survival.

Wills sums up the progress made by women in law enforcement over the past four decades. "Back in the day, in the 1970s and 1980s, women wanted to be involved in law enforcement and it was something to prove—to society and themselves—that they can do the same job. In today's environment, this is a sought after job and it's highly competitive."

Wills believes that women officers have earned respect from their colleagues and from the public because of the courage and dedication that other women have displayed on the job. "Some have paid the ultimate sacrifice and are listed on the memorial wall," he says. "We saw a lot of heroics on their part and we still do. Now we look at them in a different light."

Related: