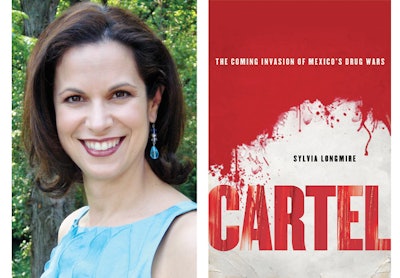

Photo: Sylvia Longmire.

Photo: Sylvia Longmire.

Author Sylvia Longmire has been studying Mexico's drug and human smuggling operations for much of her life. Her blog "Mexico's Drug War" is a must read for anyone who wants to know what is really happening on the U.S.-Mexico border, and her first book, "Cartel: The Coming Invasion of Mexico's Drug Wars," was published in September to much acclaim. Publishing trade magazine Kirkus Reviews called the book: "One stop shopping for basic knowledge about U.S.-Mexican narcotics diplomacy."

Longmire's knowledge of Mexico's drug war is hard earned. She holds a master's degree in Latin American and Caribbean Studies from the University of South Florida. After graduating from USF, she served as a special agent with the U.S. Air Force Office of Special Investigations (AFOSI). She rose to captain and was assigned as AFOSI's Latin America desk officer where she worked for eight years. From 2005 to 2009, Longmire was a senior intelligence analyst for the California state fusion center and the California Emergency Management Agency's Situational Awareness Unit. Today, she blogs on border violence and contributes articles to a wide variety of intelligence and security journals. She also serves as an expert witness in Mexican immigration and asylum cases.

POLICE Magazine/PoliceMag.com Web Editor Paul Clinton spoke with Longmire by phone several weeks before the publication of "Cartel" for a podcast. The following is an edited version of that conversation. Listen to the complete podcast at PoliceMag.com or download it via iTunes.

POLICE: How many drug trafficking organizations are actually involved in Mexico's drug war?

LONGMIRE: Just a few years ago there were only four, and then it went up to seven. In the last six months we've seen some major kingpins getting taken out, and a couple of the smaller cartels have now fractured. I would say right now there are five major cartels and at least a dozen smaller ones.

POLICE: The oldest Drug Trafficking Organization is the Sinaloa Cartel run by Chapo Guzman. Is it still the biggest trafficker of narcotics into the U.S.?

LONGMIRE: Absolutely. Not only do they have the biggest share of the drug pie, they also control probably the largest swath of territory in Mexico right now.

POLICE: What drugs are they moving?

LONGMIRE: Every cartel has its own specialty and its own mix of drugs. Sinaloa is involved in heroin, cocaine, and marijuana. Overall, the cartels get their largest chunk of the pie from marijuana.

POLICE: Mexican President Felipe Calderon declared war on the cartels in 2006. Do you feel that was kind of the trigger point for this period of extreme violence in Mexico?

LONGMIRE: It really wasn't. In 2000, Mexico went from a tradition of looking the other way when PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional, Institutional Revolutionary Party) was in office to all of a sudden a real democracy being in power. Then we saw the rise of the paramilitary organizations working as enforcement arms for the cartels-namely Los Zetas. They were former special forces troops in the Mexican military, and they went to work for the Gulf Cartel.

POLICE: Los Zetas was the enforcement arm of the Gulf Cartel. How did that relationship begin?

LONGMIRE: They were originally recruited by Osiel Cárdenas Guillén, who has been sitting in a U.S. prison since the late 1990s. In roughly 2003 to 2004, things started to blow up in Ciudad Juarez, right across the border from El Paso. And that is when the beheading started, when the dismemberment started, and when those tactics and the violence really came to full force. Now it's not enough in the Mexican drug world for just one cartel to engage in that kind of activity. It's like keeping up with the Joneses-if one cartel is doing that kind of enforcement activity to intimidate and to send messages, everybody else kind of has to keep up.

POLICE: Beheading is something we've seen from Islamist terrorists. Did the cartels learn this from the Islamist terrorists?

LONGMIRE: There's really no way to know. I've never seen any report where a cartel has said, "Yeah, we decided to start doing it because we saw al-Qaeda doing it."

POLICE: I think the greatest concern to American law enforcement officers is whether cartel violence is coming across the border. What is your opinion?

LONGMIRE: It definitely is. The cartels are getting crunched in many places by both U.S. law enforcement and Mexican law enforcement. In order to keep that drug money coming in, they are getting more desperate, which means they're more willing to engage in high-risk behavior. We've seen engagements where shots have been fired across the border. Back in 2008, we saw an incident in Phoenix where Mexican cartel members dressed up in Phoenix Police Department uniforms and raided a safe house in a very SWAT-like operation. They sprayed down the entire place with bullets, they killed the lone occupant, and then were out of there before anyone could catch them. Phoenix PD happened to be in the area. They heard the shots fired, but they were never able to really catch anybody and point the finger and say, "Yes, this particular cartel was responsible for this."

POLICE: There was also a beheading in Chandler, Ariz., last year. Was that a cartel hit?

LONGMIRE: The guy essentially owed a cartel money. I don't think it was even that much money. They went in and severed his head in an apartment in Chandler. And that's the long and short of it. What concerns me is the fact that most people in America still don't even know about that. It's the first cartel beheading we've had on this side of the border. And just the fact that it has started...should make you ask, "When is it going to happen again?"

POLICE: In our reporting we've found that a lot of the more grisly killings tend to target individuals who were moving narcotics for the cartel and potentially lost a drug load seized by law enforcement. Do you find that these grisly killings are sending a message to other cartel operators?

LONGMIRE: It's about intimidation...with a capital "I." They're saying, "We're in charge" or "We're superior to you" or "If you do this to us, this is how we're going to respond."

POLICE: Who are the U.S. victims? Are they all involved in the narco business?

LONGMIRE: The vast majority of people being kidnapped here in the U.S. or being killed in the U.S. in connection to the drug war are involved in the drug business somehow. But we are seeing exceptions to that rule. In October 2008, a six-year-old boy was kidnapped from his home in Las Vegas by Mexican cartel members because his grandfather owed a cartel one million dollars. Fortunately, that boy was released unharmed three days later. But it bothers me that an innocent six-year-old child was taken from his home in Las Vegas.

POLICE: You have a chapter in your book: "The Second Biggest Money Maker for Cartels: Kidnapping." How does the cartel make that much profit from kidnapping?

LONGMIRE: It used to be that their kidnapping targets were rivals or just somebody who owed them something, but now migrants are one of their top targets because they have realized that the migrants have paid smugglers a certain amount of money in order to bring them across the border. They have realized there's got to be some money somewhere if the migrants can afford to pay smugglers $3,000 each to take them into the United States. Plus, migrants generally have family already living in the U.S.[PAGEBREAK]

POLICE: Are people killed during these kidnappings?

LONGMIRE: Once a person is picked up, they're taken to a safe house and they're interrogated. Cartel members try to find out how much money they have, what their assets are, and basically how much they can bleed them for. Then they make contact with the family. If the family is able to round up money, they'll arrange for some kind of ransom drop. Sometimes if they're able to make the ransom payment, the victim will be let go and that's the end of that; it's just another business transaction. But if they can't make the payment, often that person is tortured and then killed.

POLICE: Last year 72 migrants were killed in San Fernando, Mexico, about 100 miles south of the U.S. border. Was that a mass kidnapping? Why would they do that?

LONGMIRE: That was a mass execution. Some reports say they were asked to pay ransom and some reports say they were being coerced to go and work for Los Zetas as either hit men or drug mules. They either couldn't pay the ransom or they weren't interested in working for the Zetas, so they were all executed. But one guy was able to get away. The details are a little sketchy still, but the fact remains that 72 migrants were executed in cold blood by a cartel.

POLICE: We've talked about a couple examples of this cross-border violence that's driven by the cartels, but it seems our own federal government is not really willing to acknowledge this. President Obama recently said in El Paso, "The border is safer than it has ever been." Why is it that the federal government seems to have trouble recognizing this problem?

LONGMIRE: Well, there's always been a huge disconnect between headquarters and officers in the field. It's like that in every government agency. There's also a disconnect between statistical evidence and anecdotal evidence. The federal government doesn't have a formal definition for spillover violence. The Texas Department of Public Safety has one, and other agencies have them, but they're not all the same, which means that local, state, and federal law enforcement and the federal government are not working off of the same sheet of music. Some sheriffs say they are being overrun with violent criminals. But you have the mayors of El Paso and San Diego saying their cities are some of the safest in the country based on crime statistics. But crime statistics don't tell the whole story. The Border Patrol has erected barriers 70 miles inside of the border so that drug runners will go around some more environmentally sensitive areas because they just don't have the personnel to arrest them and stop them. There are a lot of dangerous incidents, and it's concerning that the U.S. government says, "Well this isn't a problem and we don't have spillover violence because the statistics that the FBI is putting into this database says it's not a problem."

POLICE: Shortly after Texas Gov. Rick Perry entered the presidential race, he suggested that we need more National Guard troops on the border and potentially more Border Patrol officers. Do you see a solution for increasing security at the border?

LONGMIRE: It's a complex problem, and it requires a complex solution or combination of solutions. One of the problems I see is that both the Mexican government and the U.S. government continue to regard the drug war in Mexico as a "criminal problem." Now, there's an opposite extreme to that. Rep. Michael McCaul (R-Texas) out of Austin recently tried to introduce legislation for the U.S. government to start referring to the cartels as "terrorist organizations." They are really more like hybrid organizations: part criminal, part insurgent, part terrorist. Some people say, well you know, it's just a name, but a name means a lot when it comes to policy and allocation of money. It's like bringing a knife to a gunfight to keep calling these guys just criminals; they have evolved well beyond that.

POLICE: Mexico is generally a very poor country without much economic opportunity for many of its people. Isn't that one of the roots of the cartel violence?

LONGMIRE: Mexico needs to provide some opportunities, particularly for kids. The narco lifestyle is very, very glamorous. Some of these kids are accepting just $300 to go conduct an assassination. They're also getting paid with iPhones, mp3 players, cell phones, and cars.

POLICE: How much does official corruption protect the cartels? What is the extent, in your opinion, of police corruption in Mexico?

LONGMIRE: Corruption is everywhere, and I mean everywhere. You can safely assume that about 90 to 95 percent of police officers in Mexico-particularly at the state and local level-are either working directly for the cartels or helping the cartels.

POLICE: Mexican officers are usually poorly paid; does that drive the corruption?

LONGMIRE: There is an expression in Mexico, "plata o plomo," (silver or lead), which means, "Take the bribe or take the bullet." Corruption and bribery in all of Latin America is a way of life; it's considered socially acceptable. The bribery augments the poor pay of not just police officers, but all public servants. But now the cartels have changed that. Cops now have to take the bribe because if they don't they'll be killed or kidnapped or their families will be killed or kidnapped.

POLICE: Do you see cartel bribery taking effect here in the United States?

LONGMIRE: There is some. There have been officers in Arizona and New Mexico who have been investigated and even prosecuted. There's also been a small rise in the number of Border Patrol agents and customs inspectors who have been investigated or arrested for corruption and for accepting bribes.

POLICE: In Colombia the army went in and got Pablo Escobar. Is that something you see happening in Mexico?

LONGMIRE: Colombia is dealing with leftist communist guerilla terrorist groups that actually want to take over the government. These groups have now moved beyond that ideology; they're capitalists in the extreme. FARC is making a lot of money from the production and distribution of cocaine in Colombia. Mexico's problems are different; it has different roots. But the way that the cartels are operated is very similar in some cases to the way that the FARC is operating.

POLICE: American troops were also sent into Colombia. Would we do that in Mexico?

LONGMIRE: It was easier for American troops to go help Colombia because the Colombians didn't have to worry about national sovereignty issues. Mexico is panicked at the thought of even one American soldier stepping foot on Mexican soil. But that may be changing. The Pew Research Center conducts a poll on Mexican attitudes toward U.S. involvement in the drug war. Last year it used to be I think only 26 percent of Mexicans approved of U.S. Military intervention in the drug war, but in the most recent poll 38 percent of Mexicans supported U.S. military involvement.

POLICE: The last chapter of your book is titled "Managing a War that Can't Be Won." That sounds pretty bleak. Do you really believe things are that dire?

LONGMIRE: Everybody always asks, "Can this war be won?" This isn't like World War II. There's no way you're going to have a clear victor and a clear loser because you're never going to get rid of drug trafficking and you're never going to get rid of drug-related violence. The issue is being able to bring it down to a manageable level where people in Mexico have the freedom to live their lives and not have to worry about being caught in the crossfire. Our government and the Mexican government have to figure out how to manage the war. It's more about managing the war than winning or losing.

POLICE: You've written a great book and thank you very much for speaking with us. Just a final question: Are there some resources that you'd recommend for local law enforcement officers?

LONGMIRE: Sure, absolutely. My blog can be found at border

violenceanalysis.typepad.com, and on the front page if you scroll down, I have a blog roll that has links to other blogs and resources for law enforcement and anybody who follows events in the drug war.